Andrew Ross in the Boston Review:

The carceral system has become a vast debt machine. It creates a dizzying array of financial obligations for those unfortunate enough to be caught in its dragnet. The lowest hanging fruits are the traffic fines extracted from motorists who fall foul of a speed trap, carefully laid by officers assigned to do “revenue policing” to help fund law enforcement budgets. Judges are also under pressure from county and municipal managers to pass down ever higher fines and court fees to pay for salaries and other local government operations. For those too poor to pay, penalties and surcharges are added to the debt load every step of the way.

The carceral system has become a vast debt machine. It creates a dizzying array of financial obligations for those unfortunate enough to be caught in its dragnet. The lowest hanging fruits are the traffic fines extracted from motorists who fall foul of a speed trap, carefully laid by officers assigned to do “revenue policing” to help fund law enforcement budgets. Judges are also under pressure from county and municipal managers to pass down ever higher fines and court fees to pay for salaries and other local government operations. For those too poor to pay, penalties and surcharges are added to the debt load every step of the way.

At the other end of the system, formerly incarcerated people typically re-enter society with large debt burdens on their backs, accumulated while serving their sentences. A recent NYU study showed that individuals have to pay more than $3,700 annually just to cover basic needs (food, clothing, phone calls) during a prison stay in New York’s prisons. The numbers are much higher in states where the cost of room and board are directly borne by detainees. Wherever for-profit companies are allowed to operate, these sums are further inflated.

More here.

CABINET:

CABINET:  B

B The tile floor was cold and hard against my knees, but I couldn’t move from my spot in front of the toilet. It was the third morning that week I had spent violently throwing up because of anxiety at the prospect of going into the lab. So far, I had been able to stay home without consequence. But that day I was scheduled to meet other lab members to work on an experiment essential for my Ph.D. project. At 5:45 a.m. I let them know I wouldn’t be coming in, feeling a wave of guilt. “How did I get here?” I wondered.

The tile floor was cold and hard against my knees, but I couldn’t move from my spot in front of the toilet. It was the third morning that week I had spent violently throwing up because of anxiety at the prospect of going into the lab. So far, I had been able to stay home without consequence. But that day I was scheduled to meet other lab members to work on an experiment essential for my Ph.D. project. At 5:45 a.m. I let them know I wouldn’t be coming in, feeling a wave of guilt. “How did I get here?” I wondered. It surprises us to learn how much literature was penned in the trenches of World War I. The poems of Wilfred Owen or the early tales of Tolkien, for example, are all the more exceptional when we consider that they were composed amid states of mortal terror. But the most incredible and most stupefying example perhaps is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Less than a hundred pages long, it is a slender book that, according to its author, set about to find a “final solution” to the problems of philosophy (a phrase made even more cryptic by the knowledge that Wittgenstein and Hitler were once schoolmates). And indeed, when the Tractatus was published in the fall of 1921, Wittgenstein effectively “retired” from his trade, believing that he’d found the basement of Western philosophy and had turned off the lights when he left.

It surprises us to learn how much literature was penned in the trenches of World War I. The poems of Wilfred Owen or the early tales of Tolkien, for example, are all the more exceptional when we consider that they were composed amid states of mortal terror. But the most incredible and most stupefying example perhaps is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Less than a hundred pages long, it is a slender book that, according to its author, set about to find a “final solution” to the problems of philosophy (a phrase made even more cryptic by the knowledge that Wittgenstein and Hitler were once schoolmates). And indeed, when the Tractatus was published in the fall of 1921, Wittgenstein effectively “retired” from his trade, believing that he’d found the basement of Western philosophy and had turned off the lights when he left.

A supply chain is like a Rorschach Test: each economic analyst sees in it a pattern reflecting his or her own preconceptions. This may be inevitable, since everyone is a product of differing educations, backgrounds, and prejudices. But some observed patterns are more plausible than others.

A supply chain is like a Rorschach Test: each economic analyst sees in it a pattern reflecting his or her own preconceptions. This may be inevitable, since everyone is a product of differing educations, backgrounds, and prejudices. But some observed patterns are more plausible than others. We’re doing astonishingly well, and most environmental trends are going in the right direction. Carbon emissions have declined more in the United States than in any other country over the last twenty years, mostly due to fracking. Carbon emissions peaked in Europe in the mid-seventies, in the main European countries I should say. And some people think carbon emissions have peaked globally. I personally think they probably have another ten years of growth, but we’re close to global peak emissions, after which they will go down. We appear to be at peak agricultural land use, and that will go down. So Malthus was sort of spectacularly wrong, both on human progress, but also environmental progress.

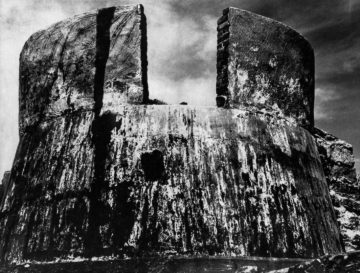

We’re doing astonishingly well, and most environmental trends are going in the right direction. Carbon emissions have declined more in the United States than in any other country over the last twenty years, mostly due to fracking. Carbon emissions peaked in Europe in the mid-seventies, in the main European countries I should say. And some people think carbon emissions have peaked globally. I personally think they probably have another ten years of growth, but we’re close to global peak emissions, after which they will go down. We appear to be at peak agricultural land use, and that will go down. So Malthus was sort of spectacularly wrong, both on human progress, but also environmental progress. EARLY IN JULY 1958, the Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada, then aged twenty-five and a staffer at the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho, visited Hiroshima for a cover story to run in the month following. He was there to photograph another photographer, Ken Domon, whose book Hiroshima had been published in the spring. Among Domon’s subjects: the scarred bodies of survivors of the atomic-bomb attack of August 6, 1945, and the skeletal dome of the city’s riverside industrial exhibition hall. When he had finished his assignment, Kawada lingered in the ruins below the Genbaku Dome, where brick and concrete walls were covered with stains composing, as he put it, “an audibly violent whirlpool.” Kawada took no photographs of the enigmatic markings, but returned two years later with a 4 x 5 view camera, and began making long exposures in “this terrifying, unknown place.”

EARLY IN JULY 1958, the Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada, then aged twenty-five and a staffer at the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho, visited Hiroshima for a cover story to run in the month following. He was there to photograph another photographer, Ken Domon, whose book Hiroshima had been published in the spring. Among Domon’s subjects: the scarred bodies of survivors of the atomic-bomb attack of August 6, 1945, and the skeletal dome of the city’s riverside industrial exhibition hall. When he had finished his assignment, Kawada lingered in the ruins below the Genbaku Dome, where brick and concrete walls were covered with stains composing, as he put it, “an audibly violent whirlpool.” Kawada took no photographs of the enigmatic markings, but returned two years later with a 4 x 5 view camera, and began making long exposures in “this terrifying, unknown place.” T

T It was a Monday morning, which was reason enough to meditate. I was anxious about the day ahead, and so, as I’ve done countless times over the past few years, I settled in on my couch for a short meditation session. But something was different this morning.

It was a Monday morning, which was reason enough to meditate. I was anxious about the day ahead, and so, as I’ve done countless times over the past few years, I settled in on my couch for a short meditation session. But something was different this morning. I have seen many things (corpses, the Northern Lights, a beached whale), but a few sights have left a particularly vivid impression. One is of a boy I spotted in Istanbul eighteen years ago. He was fifteen or so, with a pathetic whispy moustache, wearing a suit for what appeared to be the first time. We were in the textile district of Zeytinburnu, and it seemed to me he was likely beginning a new life in his father’s small business, though I could be wrong. Whatever the occasion, the boy had deemed fitting to commission the labor of an even smaller boy, nine years old or so, to shine his shoes. The shoeshine kid was kneeling on the ground, scrubbing away with rags and polish from his portable kit, a borderline-homeless street gamin for whom all of our rhetoric about the sacred innocence of childhood means nothing at all. The fifteen-year-old stared down haughtily, like a small sovereign, and the nine-year-old, knowing his place, did not dare even to look up.

I have seen many things (corpses, the Northern Lights, a beached whale), but a few sights have left a particularly vivid impression. One is of a boy I spotted in Istanbul eighteen years ago. He was fifteen or so, with a pathetic whispy moustache, wearing a suit for what appeared to be the first time. We were in the textile district of Zeytinburnu, and it seemed to me he was likely beginning a new life in his father’s small business, though I could be wrong. Whatever the occasion, the boy had deemed fitting to commission the labor of an even smaller boy, nine years old or so, to shine his shoes. The shoeshine kid was kneeling on the ground, scrubbing away with rags and polish from his portable kit, a borderline-homeless street gamin for whom all of our rhetoric about the sacred innocence of childhood means nothing at all. The fifteen-year-old stared down haughtily, like a small sovereign, and the nine-year-old, knowing his place, did not dare even to look up. When it comes to climate finance, the gap between what is needed and what is on the table is dizzying. The talk at the conference was all about the annual $100bn (£75bn) that rich countries had promised to poorer nations

When it comes to climate finance, the gap between what is needed and what is on the table is dizzying. The talk at the conference was all about the annual $100bn (£75bn) that rich countries had promised to poorer nations