Category: Recommended Reading

Why We Are Not Pagans

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter, Hinternet:

Just minutes after St. Nicholas was born, on December 6, he stood up on his own two feet in the basin where the midwives washed him, and completed the task himself. Then the babe grabbed a knife from the table and severed his own umbilical cord. Through the rest of his infancy he refused to nurse more than twice a week, and only ever on Wednesdays and Fridays. As Nicholas grew older he developed a sharp hatred of sin, and wept whenever he witnessed it. Having inherited a great wealth from his parents, he decided to fight sin through what you might today call “effective altruism”. When he overheard his neighbor announcing a plan to sell his two daughters into prostitution in order to lighten his debts, Nicholas contrived to throw a sack of gold coins through the neighbor’s window in the middle of the night (the sled and reindeer, we may imagine, are later accretions upon the legend). After a life of such good works, when he died in 313 AD, oil poured from his head, and water from his feet, and continued to pour for some centuries after that from the site of his burial, when such things as this still occurred.

Just minutes after St. Nicholas was born, on December 6, he stood up on his own two feet in the basin where the midwives washed him, and completed the task himself. Then the babe grabbed a knife from the table and severed his own umbilical cord. Through the rest of his infancy he refused to nurse more than twice a week, and only ever on Wednesdays and Fridays. As Nicholas grew older he developed a sharp hatred of sin, and wept whenever he witnessed it. Having inherited a great wealth from his parents, he decided to fight sin through what you might today call “effective altruism”. When he overheard his neighbor announcing a plan to sell his two daughters into prostitution in order to lighten his debts, Nicholas contrived to throw a sack of gold coins through the neighbor’s window in the middle of the night (the sled and reindeer, we may imagine, are later accretions upon the legend). After a life of such good works, when he died in 313 AD, oil poured from his head, and water from his feet, and continued to pour for some centuries after that from the site of his burial, when such things as this still occurred.

More here.

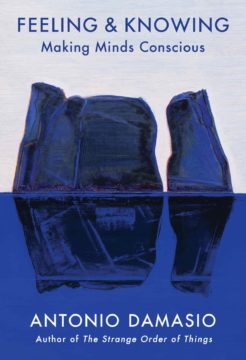

In “Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious,” neuroscientist Antonio Damasio explores the mystery of consciousness

Emily Cataneo in Undark:

Consciousness is such a slippery and ephemeral concept that it doesn’t even have its own word in many Romance languages, but nevertheless it’s a hot topic these days. “Feeling & Knowing” is the result of Damasio’s editor’s request to weigh in on the subject by writing a very short, very focused book. Over 200 pages, Damasio ponders profound questions: How did we get here? How did we develop minds with mental maps, a constant stream of images, and memories — mechanisms that exist symbiotically with the feelings and sensations in our bodies that we then, crucially, relate back to ourselves and associate with a sense of personhood?

Consciousness is such a slippery and ephemeral concept that it doesn’t even have its own word in many Romance languages, but nevertheless it’s a hot topic these days. “Feeling & Knowing” is the result of Damasio’s editor’s request to weigh in on the subject by writing a very short, very focused book. Over 200 pages, Damasio ponders profound questions: How did we get here? How did we develop minds with mental maps, a constant stream of images, and memories — mechanisms that exist symbiotically with the feelings and sensations in our bodies that we then, crucially, relate back to ourselves and associate with a sense of personhood?

Damasio argues that the answers are not simple (not so simple as an algorithm, anyway) but it’s also not as complex as some theorists and scientists believe.

More here.

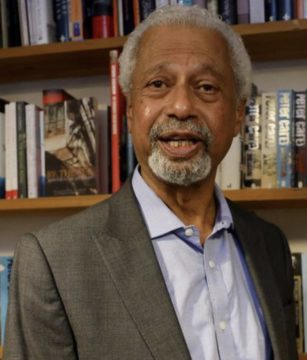

‘Paradise’: This novel of a young man’s journeys shows Nobel laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah at his best

Sayari Debnath in Scroll.in:

Many readers around the world are still just discovering Abdulrazak Gurnah. After his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021 – which almost no one saw coming – the 72-year-old Zanzibar-born author is finally in the limelight that was perhaps due to him for a few decades now.

Many readers around the world are still just discovering Abdulrazak Gurnah. After his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021 – which almost no one saw coming – the 72-year-old Zanzibar-born author is finally in the limelight that was perhaps due to him for a few decades now.

Born in 1948, Gurnah spent his childhood in the islands of Zanzibar before escaping to England in the 1960s. This was shortly after the island gained independence from British colonial rule in December 1963 and went through a revolution. However, the post-revolution regime ushered in the oppression and persecution of citizens of Arab origin.

At the height of the civil unrest, massacres became a common occurrence on the island. Gurnah belonged to a persecuted minority ethnic group and, after finishing school, was forced to leave his family and flee the country.

More here.

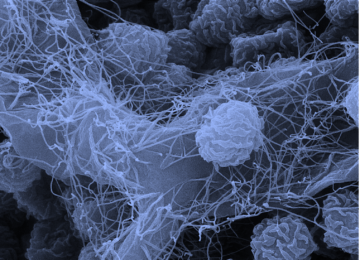

Carl Zimmer: Are Viruses Alive?

Call Us What We Carry – symphony of hope and solidarity

Kit Fan in The Guardian:

What happens when words spoken on Capitol Hill make us shiver? Amanda Gorman’s luminous poem The Hill We Climb was addressed to Joe Biden and “the world”. Inaugural poems are a fiendishly difficult genre, attempted only six times since JF Kennedy’s ceremony. However, such “occasional” poems play an important cultural role, especially in our time when no public rhetoric and few common values can be taken for granted, as the poet addresses and repairs the damaged foundations of the state itself.

What happens when words spoken on Capitol Hill make us shiver? Amanda Gorman’s luminous poem The Hill We Climb was addressed to Joe Biden and “the world”. Inaugural poems are a fiendishly difficult genre, attempted only six times since JF Kennedy’s ceremony. However, such “occasional” poems play an important cultural role, especially in our time when no public rhetoric and few common values can be taken for granted, as the poet addresses and repairs the damaged foundations of the state itself.

A soaring sense of history and solidarity pervades Gorman’s debut collection. Part elegy, part documentary record, and part witness statement, Call Us What We Carry is first and foremost “a letter to the world”, a phrase she borrows from Emily Dickinson. Like Dickinson’s, Gorman’s poetry puts immense pressure on our present moment, committing itself to an archaeology of our past and conservation of our future. It urges us to revisit the chequered history of intersectional injustices and re-evaluate our fragile species, systems and planet, engulfed by the pandemic, personal grief and public grievances.

“What happened to us”, Gorman writes, “Happened through us.” One of the most haunting things about her book is its retreat from the first-person singular. “I” exists sparingly, peripherally. By contrast, the all-inclusive trio “we”, “us” and “our” occur more than 1,500 times in her shape-shifting poems, a rare feat in the age of overwhelming selfhood. Gorman’s affirmative choric we echoes Martin Luther King’s memorial dream and John Lennon’s utopian lyricism, but her music also draws on the new dimension opened up by trailblazing poets such as Elizabeth Alexander, Anne Carson and Tracy K Smith. She challenges Walt Whitman’s “I am large. I contain multitudes.” In her book, it is we who contain multitudes, and a shared vision, grief and responsibility, as she affirms that “This book is awake. / This book is a wake. / For what is a record but a reckoning?”

More here.

What future science will we invent by 2030?

Jenna Daroczy in CSIROscope:

Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021.

Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021.

…Dr Alan Richardson is the Chief Research Scientist in our Microbiomes for One System Health program. This team will develop our capabilities across agriculture, land-use and human health. “Microorganisms hold huge potential because they are integral in the makeup of all plants and animals. And they are the key drivers of biological and environmental processes,” Alan said. “Our approach will reflect the interconnectivity of microbiomes across systems. It will identify new opportunities to manage the environment, transform food production, waste management, and plant, animal and human health.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Teaching Poetry In A Men’s High Security Prison

I was searched at every edge. I wanted everyone, including me, to be innocent. One inmate squeezed my hand like a letter he’d been hoping for. In the workshop, he read his poem. I applauded. He hugged me. He smelt of stale soap. Leaning in, his stubble sandpapered my softer jaw. He tells me what he did.

He was drunk the night he blacked out, opened his eyes in the kitchen, his wife who wanted divorce, on the floor, dead. I see his wedding ring. I wish I knew her name so I could plant it here.

The next week, the poetry showcase is almost cancelled which causes the inmates to riot. The inmates won. I arrived at the prison for the last time. Flowers placed on all the tables. An inmate read, held himself like his mother’s favorite plant pot. After his poem, everyone applauded, even the guards. The tattooed fists of all those muscular men reached for flowers.

Thrown at men’s feet,

Anaconda red tulips,

Jewels of blood.

Tuesday, December 7, 2021

Ak Dan Gwang Chil (ADG7)

The Manson Family

Rachel Monroe at The Believer:

One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge.

One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge.

more here.

The Lighted Window: Evening Walks Remembered

Seamus Perry at Literary Review:

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind.

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind.

more here.

A new book about the Boeing 737 MAX disaster

Maureen Tkacik in The American Prospect:

Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been delivered to the Jakarta Airport terminal of Indonesia’s reigning discount carrier Lion Air. Fishermen described the fuselage plunging nose-first, directly perpendicular to the Java Sea, at speeds many times that of Komarov’s four-and-a-half mile descent from the half-baked Soyuz 1, with its malfunctioning parachutes. A 48-year-old diver dispatched to plumb the deep sea floor for body parts and the elusive cockpit voice recorder became the 190th fatality. As with the Soyuz, in which the famous cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was said to have detailed 200 outstanding manufacturing defects in a memo to superiors, the 737 MAX had been the subject of numerous ignored whistleblower reports, tormented confessions, and abrupt career changes; the general manager of the plane’s final assembly line outside Seattle had resigned in despair the week Lion Air took delivery.

Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been delivered to the Jakarta Airport terminal of Indonesia’s reigning discount carrier Lion Air. Fishermen described the fuselage plunging nose-first, directly perpendicular to the Java Sea, at speeds many times that of Komarov’s four-and-a-half mile descent from the half-baked Soyuz 1, with its malfunctioning parachutes. A 48-year-old diver dispatched to plumb the deep sea floor for body parts and the elusive cockpit voice recorder became the 190th fatality. As with the Soyuz, in which the famous cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was said to have detailed 200 outstanding manufacturing defects in a memo to superiors, the 737 MAX had been the subject of numerous ignored whistleblower reports, tormented confessions, and abrupt career changes; the general manager of the plane’s final assembly line outside Seattle had resigned in despair the week Lion Air took delivery.

But three years later, nothing has surfaced to suggest that any senior official at Boeing took so much as a passing glance at the corpse stew its greed chucked into the Java Sea, much less any semblance of responsibility.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Joshua Greene on Morality, Psychology, and Trolley Problems

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard.

We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard.

More here.

Time to Overhaul the Global Financial System

Jeffrey D. Sachs in Project Syndicate:

At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many.

At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many.

Economic development depends on investments in three main kinds of capital: human capital (health and education), infrastructure (power, digital, transport, and urban), and businesses. Poorer countries have lower levels per person of each kind of capital, and therefore also have the potential to grow rapidly by investing in a balanced way across them. These days, that growth can and should be green and digital, avoiding the high-pollution growth of the past.

Global bond markets and banking systems should provide sufficient funds for the high-growth “catch-up” phase of sustainable development, yet this doesn’t happen. The flow of funds from global bond markets and banks to developing countries remains small, costly to the borrowers, and unstable. Developing-country borrowers pay interest charges that are often 5-10% higher per year than the borrowing costs paid by rich countries.

Developing country borrowers as a group are regarded as high risk. The bond rating agencies assign lower ratings by mechanical formula to countries just because they are poor. Yet these perceived high risks are exaggerated, and often become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

More here.

Stephen Sondheim had an interesting discussion with Steven Pinker in 2016

Tuesday Poem

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

The big idea: how much do we really want to know about our genes?

Daniel Davis in The Guardian:

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

Over the next few weeks, she Googled, read journal articles, and tried to become an expert patient in what was quite a rare genetic disorder. There wasn’t much to go on, and, not being a scientist herself, it was hard for her to evaluate what she did find. She learned that a link between mutations in this particular gene and connective tissue problems had only recently been discovered. A few years earlier this disease did not exist, or at least it had yet to be named. Over time, some details emerged. Nobody had ever seen her own family’s particular mutation in anyone else. So that meant it was very hard to know what to make of her situation. Her risk of a heart problem was surely increased, but nobody could say by how much.

More here.

Are My Stomach Problems Really All in My Head?

Constance Sommer in The New York Times:

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

“I’m so sorry, honey,” I said. “I feel really, really bad.” And I did. I was on the verge of tears, as much out of self-pity and shame as any maternal concern. Eli shook his head. “It’s OK, Mom. It’s not your fault.” But it was. Because of me — or, to be precise, my digestive system — we would not eat until we reached Amarillo, Texas, at 10 p.m., and bought frozen food from a grocery store near our Airbnb. My gut is not a carefree traveler. Ingest the wrong items, and my stomach feels as though someone’s scoured it with a Brillo pad. For the next few hours, I may also experience migraines, achy joints and a foggy, feverish sensation like I’m coming down with the flu. My doctors call this irritable bowel syndrome, or I.B.S. I call it a terrible shame.

More here.

Sunday, December 5, 2021

Wisława Szymborska: Advice for Writers

Joanna Kavenna in Literary Review:

Inverting the old cliché, Christopher Hitchens said, ‘Everyone has a book in them and that, in most cases, is where it should stay.’ The journalist and satirist Karl Kraus agreed: journalists, especially, should never write novels. This was self-satire, partly. Yet there are writers who can barely go to the shops without publishing a voluminous account immediately afterwards. At the other end of this unscientific spectrum are writers who destroy their work, either because they think it’s rubbish (Joyce, Stevenson, etc) or because they’ve become recently convinced it was written by the Devil (Gogol). Some people doubt themselves far too much, others not remotely enough.

Inverting the old cliché, Christopher Hitchens said, ‘Everyone has a book in them and that, in most cases, is where it should stay.’ The journalist and satirist Karl Kraus agreed: journalists, especially, should never write novels. This was self-satire, partly. Yet there are writers who can barely go to the shops without publishing a voluminous account immediately afterwards. At the other end of this unscientific spectrum are writers who destroy their work, either because they think it’s rubbish (Joyce, Stevenson, etc) or because they’ve become recently convinced it was written by the Devil (Gogol). Some people doubt themselves far too much, others not remotely enough.

With some or none of this in mind, the Polish author Wisława Szymborska, who died in 2012, destroyed 90 per cent of her writing. Despite that (or maybe because of it), she won the Nobel Prize in 1996 for ‘poetry that … allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality’. I have no idea what that means either.

More here.

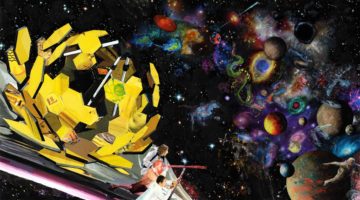

The Webb Space Telescope Will Rewrite Cosmic History. If It Works.

Natalie Wolchover in Quanta:

To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine.

To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine.

But to read that early chapter in the universe’s history — to learn the nature of those first, probably gargantuan stars, to learn about the invisible matter whose gravity coaxed them into being, and about the roles of magnetism and turbulence, and how enormous black holes grew and worked their way into galaxies’ centers — an exceptional mirror is not nearly enough.

More here.