Ashutosh Varshney in the Boston Review:

This August India celebrates seventy-three years as an independent nation. During these decades of independence, the country has been run democratically (aside from the twenty-one months of the infamous Emergency from 1975 to 1977). With the exception of Costa Rica, no other developing country has enjoyed as long a democratic run since World War II. And in the case of Costa Rica, it is worth bearing in mind that the country is small, with a GDP per capita six times that of India’s (in 2019 Costa Rica’s GDP per capita was $12,238, while India’s was $2,104). Modern democratic theory holds that democracies generally live longer when their citizens have higher levels of income. And in societies with lower incomes, the mortality rate of democracy is often high. For decades now India has defied this conventional scholarly wisdom.

This August India celebrates seventy-three years as an independent nation. During these decades of independence, the country has been run democratically (aside from the twenty-one months of the infamous Emergency from 1975 to 1977). With the exception of Costa Rica, no other developing country has enjoyed as long a democratic run since World War II. And in the case of Costa Rica, it is worth bearing in mind that the country is small, with a GDP per capita six times that of India’s (in 2019 Costa Rica’s GDP per capita was $12,238, while India’s was $2,104). Modern democratic theory holds that democracies generally live longer when their citizens have higher levels of income. And in societies with lower incomes, the mortality rate of democracy is often high. For decades now India has defied this conventional scholarly wisdom.

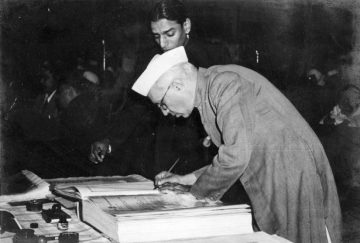

Surprise at India’s democratic success is well documented. Barrington Moore was the first major social scientist to note the uncommon and the unexpected. In 1966 he observed that “as a political species, [India] does belong to the modern world. At the time of Nehru’s death in 1964 political democracy had existed for seventeen years. If imperfect, the democracy was no mere sham.” Half a decade later, in 1971, Robert Dahl—arguably the most influential figure in democratic theory—wrote that India was a “deviant case . . . indeed a polyarchy.”

More here.