Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova: The founding fathers of neoliberalism—Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and others, as you describe in your book, have created the basis for today’s global world order. They laid the foundation for institutions including the European Union and the World Trade Organization (WTO). What was particular about the Geneva School of neoliberalism?

Quinn Slobodian: What occurred to me was that capitalism hadn’t really had to deal with democracy until the twentieth century. It could reproduce itself and all of its inequalities by simply keeping some people out of the political picture, and denying them a voice in the political process.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most of the world was in colonial status. The parts of the world that were in the metropole—the center of the empire, or had independence like the United States or Latin American countries—did not have anything close to universal suffrage. Women in every case were still denied the right to vote—allowing women to vote happened experimentally within the Paris Commune in the 1870s, but was quickly withdrawn and was only rolled out in exceptional cases more after the First World War. And in places like France, not until the Second World War.

So, the core question for Vienna school neoliberals in the 1920s and 1930s was first of all how to expand the voice within rich Western populations to include people without property and women. And then how to expand it beyond Europe to the former colonial countries of Asia, Africa, and parts of Latin America. And how to do that while preserving a system which has been proven to produce jaw-dropping inequalities between populations and parts of the world.

The first problem that they saw was decolonization. The dissolution of the Habsburg Empire after the First World War accompanied the end of the Russian and Ottoman Empires. It was the triumph of the nationality principle for the first time. That also came along with a certain idea of self-determination and popular sovereignty at the national level, which was more asserted than practiced until after the First World War.

More here.

The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on

The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on  On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists.

On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists. Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs.

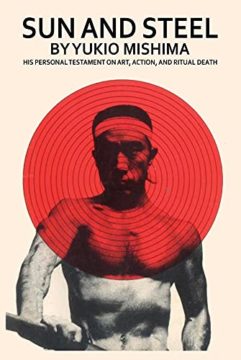

Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs. He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword.

He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword. A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.”

A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.” Variants in

Variants in The Biden administration’s mantra for the Middle East is simple: “end the ‘forever wars.’” The White House is preoccupied with managing the challenge posed by China and aims to disentangle the United States from the Middle East’s seemingly endless and unwinnable conflicts. But the United States’ disengagement threatens to leave a political vacuum that will be filled by sectarian rivalries, paving the way for a more violent and unstable region.

The Biden administration’s mantra for the Middle East is simple: “end the ‘forever wars.’” The White House is preoccupied with managing the challenge posed by China and aims to disentangle the United States from the Middle East’s seemingly endless and unwinnable conflicts. But the United States’ disengagement threatens to leave a political vacuum that will be filled by sectarian rivalries, paving the way for a more violent and unstable region. On August 1 the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a coalition of over sixty organizations, rolled out “

On August 1 the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a coalition of over sixty organizations, rolled out “

Daniel Borzutzky’s poetry is not an easy, elegant read: trauma, prisons, torture, murders, and arresting phrases like “rotten carcass economy” and “the blankest of times” recur ad nauseam. To read Borzutzky is, in other words, to reckon with the “grotesque.”

Daniel Borzutzky’s poetry is not an easy, elegant read: trauma, prisons, torture, murders, and arresting phrases like “rotten carcass economy” and “the blankest of times” recur ad nauseam. To read Borzutzky is, in other words, to reckon with the “grotesque.” Quantum mechanics is nearly one hundred years old, and yet the challenge it presents to the imagination is so great that scientists are still coming to terms with some of its most basic implications. Here I will describe some theoretical insights and recent experimental results that are leading physicists to revise and expand their ideas about what quantum-mechanical particles are and how they behave. These new ideas are centered around a topic traditionally known as quantum statistics. The name is misleading: the basic physical phenomena do not involve statistics in the usual sense. A better title might have been the quantum mechanics of identity, but the new developments make that name obsolete too. A more accurate description would be the quantum mechanics of world-line topology. Since that is quite a mouthful, most researchers now simply refer to anyon physics.

Quantum mechanics is nearly one hundred years old, and yet the challenge it presents to the imagination is so great that scientists are still coming to terms with some of its most basic implications. Here I will describe some theoretical insights and recent experimental results that are leading physicists to revise and expand their ideas about what quantum-mechanical particles are and how they behave. These new ideas are centered around a topic traditionally known as quantum statistics. The name is misleading: the basic physical phenomena do not involve statistics in the usual sense. A better title might have been the quantum mechanics of identity, but the new developments make that name obsolete too. A more accurate description would be the quantum mechanics of world-line topology. Since that is quite a mouthful, most researchers now simply refer to anyon physics. Last week, in its

Last week, in its  “We were superior to the god who had created us,” Adam recalled not long before he died, age seven hundred. According to The Apocalypse of Adam, a Coptic text from the late first century CE, discovered in Upper Egypt in 1945, Adam told his son Seth that he and Eve had moved as a single magnificent being: “I went about with her in glory.” The fall was a plunge from unity into human difference. “God angrily divided us,” Adam recounted. “And after that we grew dim in our minds…” Paradise was a lost sense of self, and it was also a place that would appear on maps, wistfully imagined by generations of Adam’s descendants. In the fifteenth century, European charts located Eden to the east, where the sun rises—an island ringed by a wall of fire. With the coordinates in their minds, Europe’s explorers could envisage a return to wholeness, to transcendence, to the godhood that had once belonged to man.

“We were superior to the god who had created us,” Adam recalled not long before he died, age seven hundred. According to The Apocalypse of Adam, a Coptic text from the late first century CE, discovered in Upper Egypt in 1945, Adam told his son Seth that he and Eve had moved as a single magnificent being: “I went about with her in glory.” The fall was a plunge from unity into human difference. “God angrily divided us,” Adam recounted. “And after that we grew dim in our minds…” Paradise was a lost sense of self, and it was also a place that would appear on maps, wistfully imagined by generations of Adam’s descendants. In the fifteenth century, European charts located Eden to the east, where the sun rises—an island ringed by a wall of fire. With the coordinates in their minds, Europe’s explorers could envisage a return to wholeness, to transcendence, to the godhood that had once belonged to man.