Daniel Björkegren in Nature:

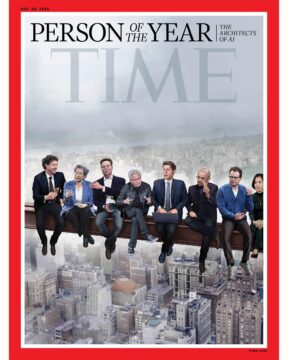

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

Given the high stakes, many researchers and policymakers are increasingly attempting to precisely quantify the causal impact of AI through natural experiments and randomized controlled trials. In such studies, one group gains access to an AI tool while another continues under normal conditions; other factors are held fixed. Researchers can then analyse outcomes such as productivity, satisfaction and learning.

Yet, when applied to AI, this type of evidence faces two challenges.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

More than international sanctions, more than its stifling theocracy, more than recent bombardment by Israel and the U.S. — Iran’s greatest current existential crisis is what hydrologists are calling its rapidly approaching “water bankruptcy.”

More than international sanctions, more than its stifling theocracy, more than recent bombardment by Israel and the U.S. — Iran’s greatest current existential crisis is what hydrologists are calling its rapidly approaching “water bankruptcy.” Jensen Huang needs a moment.

Jensen Huang needs a moment. A

A  The most widely endorsed reason productivity growth has faltered is that we are running out of good ideas. As this narrative has it, the many scientific and technology advances responsible for driving economic growth in the past were low-hanging fruit. Now the tree is more barren. Novel advances, we should expect, are harder to come by, and historical growth may thus be difficult to sustain. In the extreme, this may lead to the end of progress altogether.

The most widely endorsed reason productivity growth has faltered is that we are running out of good ideas. As this narrative has it, the many scientific and technology advances responsible for driving economic growth in the past were low-hanging fruit. Now the tree is more barren. Novel advances, we should expect, are harder to come by, and historical growth may thus be difficult to sustain. In the extreme, this may lead to the end of progress altogether. In August, a team of mathematicians posted a paper claiming to solve a major problem in algebraic geometry — using entirely alien techniques. It instantly captivated the field, stoking excitement in some mathematicians and skepticism in others.

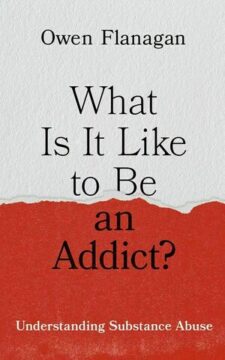

In August, a team of mathematicians posted a paper claiming to solve a major problem in algebraic geometry — using entirely alien techniques. It instantly captivated the field, stoking excitement in some mathematicians and skepticism in others. It is a rare book that combines rigorous argument, scientific fluency, and broad accessibility, but Owen Flanagan has managed that trifecta in his new monograph on the philosophy and science of addictions. What is it Like to Be an Addict? should serve as a standard reference-point for philosophers interested in the health sciences moving forward, as it clarifies and refines many of the basic questions in these fields. It is also a book that may be read with profit by anyone with even a passing interest in the science or ethics of addiction.

It is a rare book that combines rigorous argument, scientific fluency, and broad accessibility, but Owen Flanagan has managed that trifecta in his new monograph on the philosophy and science of addictions. What is it Like to Be an Addict? should serve as a standard reference-point for philosophers interested in the health sciences moving forward, as it clarifies and refines many of the basic questions in these fields. It is also a book that may be read with profit by anyone with even a passing interest in the science or ethics of addiction. One side fears the shredding of safety nets, federal programs, and commitments to inclusion and honest history. The other side fears the destruction of traditional family mores, religion, and parental control.

One side fears the shredding of safety nets, federal programs, and commitments to inclusion and honest history. The other side fears the destruction of traditional family mores, religion, and parental control. Gertrude Stein had no doubt that she was a genius. “I have been the creative literary mind of the century,” she once boasted. “Think of the Bible and Homer think of Shakespeare and think of me.” Some years earlier, she informed a baffled magazine editor who had rejected her writing that she was producing “the only important literature that has come out of America since Henry James.” She knew her work was unconventional—repetitive, hermetic, its apparent crudeness belying immense psychological and literary sophistication—but was supremely confident that, in time, it would be recognized as something of enduring cultural value. “For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause everybody accepts,” she observed in 1926 about the reception of avant-garde art. There was no question in her mind that her own contribution would eventually be accepted: She simply had to wait.

Gertrude Stein had no doubt that she was a genius. “I have been the creative literary mind of the century,” she once boasted. “Think of the Bible and Homer think of Shakespeare and think of me.” Some years earlier, she informed a baffled magazine editor who had rejected her writing that she was producing “the only important literature that has come out of America since Henry James.” She knew her work was unconventional—repetitive, hermetic, its apparent crudeness belying immense psychological and literary sophistication—but was supremely confident that, in time, it would be recognized as something of enduring cultural value. “For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause everybody accepts,” she observed in 1926 about the reception of avant-garde art. There was no question in her mind that her own contribution would eventually be accepted: She simply had to wait. From the time of Aristotle through to the 1500s, the dominant model of the universe had the sun, planets, and stars orbiting around the Earth. This simple model, however, did not match what could be seen in the skies. Venus appears in the evening or morning. It never crosses the night sky as we would expect if it were orbiting the Earth. Jupiter moves across the night sky but will abruptly turn around and go back the other way.

From the time of Aristotle through to the 1500s, the dominant model of the universe had the sun, planets, and stars orbiting around the Earth. This simple model, however, did not match what could be seen in the skies. Venus appears in the evening or morning. It never crosses the night sky as we would expect if it were orbiting the Earth. Jupiter moves across the night sky but will abruptly turn around and go back the other way. For a mouse several times its size, a sting from the “

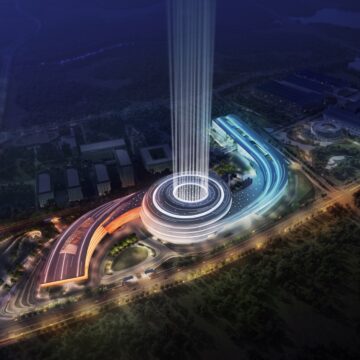

For a mouse several times its size, a sting from the “ On a leafy campus in eastern China, crews are working day and night to finish a mammoth round structure with two sweeping arms the length of aircraft carriers.

On a leafy campus in eastern China, crews are working day and night to finish a mammoth round structure with two sweeping arms the length of aircraft carriers. Some of the premium increases can be attributed to an increase in

Some of the premium increases can be attributed to an increase in