Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Scott Aaronson: How Close Are We to Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Willie Nelson Sees America

Alex Abramovich at The New Yorker:

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

On September 12th, Nelson drove down to the Freedom Mortgage Pavilion, in Camden. His band, a four-piece, was dressed all in black; Nelson wore black boots, black jeans, and a Bobby Bare T-shirt. His hair, which is thicker and darker than it appears under stage lights, hung in two braids to his waist. A scrim masked the front of the stage, and he walked out unseen, holding a straw cowboy hat. Annie, his wife of thirty-four years, rubbed his back and shoulders. A few friends watched from the wings: members of Sheryl Crow’s band, which had opened for him, and John Doe, the old punk musician, who had flown in from Austin. (At the next show, in Holmdel, Bruce Springsteen showed up.) Out front, big screens played the video for Nelson’s 1986 single “Living in the Promiseland.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Raja Shehadeh Believes Israelis and Palestinians Can Still Find Peace

David Marchese in the New York Times:

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

That work, defined by precise description and delicately deployed emotion, has won him widespread acclaim. Shehadeh’s 2007 book, “Palestinian Walks: Forays Into a Vanishing Landscape,” won Britain’s Orwell Prize for political writing. Here in the United States, his book “We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I” was a finalist for the 2023 National Book Award.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Metabolism is the next frontier in cancer treatment: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

Siddhartha Mukherjee in Stat 10:

In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

For a century, metabolism was oncology’s prologue. In the 1920s, Otto Warburg observed that many cancer cells consume glucose voraciously and convert much of that glucose to lactate even when oxygen is plentiful, a seemingly wasteful choice that became a metabolic signature of malignancy. That insight eventually receded into a footnote while genetics took the stage. But tumors are not static genotypes; they are shape-shifters that adapt to therapy by rewiring their fuel lines.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Steely Dan

Philip Clark at the NYRB:

As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s.

As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s.

In albums like Can’t Buy a Thrill (1972), Pretzel Logic (1974), and Aja (1977), they cultivated a sleek, polished pop that was marinated in jazz, blues, Latin, and rock and roll. Their songs had both a melodic, high-fidelity sheen—a gift to radio airplay—and a level of compositional integrity and instrumental elan that left aficionados agog. Lyrically, they developed a fixation—naysayers considered it an affectation—with pairing waspish observations about social outsiders, the venality of pop culture, and men riding out their midlife crises with relentlessly feel-good music, the harmonies never smudging in sympathy with the deranged words.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Scientists Just Developed a Lasting Vaccine to Prevent Deadly Allergic Reactions

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines.

‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines.

Over three million people worldwide tiptoe around a food allergy. Even more experience watery eyes, runny noses, and uncontrollable sneezing from dust, pollen, or cuddling with a fluffy pet. Over-the-counter medications can control symptoms. But in some people, allergic responses turn deadly.

In anaphylaxis, an overactive immune system releases a flood of inflammatory chemicals that closes up the throat. This chemical storm stresses out the heart and blood vessels and limits oxygen to the brain and other organs. Early diagnosis, especially of shellfish or nut allergies, helps people avoid these foods. And in an emergency, EpiPens loaded with epinephrine can relax airways and save lives. But the pens must be carried at all times, and patients—especially young children—struggle with this.

An alternative is to train the immune system to neutralize its over-zealous response. This month, a team from the University of Toulouse in France presented a long-lasting treatment that fights off anaphylactic shock in mice. Using a vaccine, they rewired part of the immune system to battle Immunoglobulin E (IgE), a protein that’s involved in severe allergic reactions. A single injection into mice launched a tsunami of antibodies against IgE, and levels of those antibodies remained high for at least 12 months—which is over half of a mouse’s life. Despite triggering an immune civil war, the mice’s defenses were still able to fight a parasitic infection. The vaccine is, in theory, a blanket therapy for most food allergies, from peanuts to shellfish.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, December 21, 2025

Joe Ely (1947 – 2025) Singer, Guitarist, Songwriter

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Girl with a Blue Scarf

She sits against the porridge-coloured wall

watchful and suspicious,

with the look of a frightened fawn,

her oval face and Slavic eyes wary

beneath her ragged crow-black fringe,

her little rodent paws curled

in the mulberry pool of her skirt.

The room is freezing. The grate empty.

The carte de charbon far too dear.

Both of them might well ask

what they’re doing here,

shivering in this pale dun light,

one watchful, the other watching.

The concierge from the rue de l’Ouest,

the young painter from Tenby.

Late afternoon. Her paint is dry

as wood ash, laid down with tiny,

speckled strokes until the girl

appears timorous as a thought.

Silent as prayer.

by Sue Hubbard

From God’s Little Artist:

poems on the life of Gwen John

published @Seren Books

The Painting Here:

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rob Reiner (1947 – 2025) Actor and Filmmaker

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Peter Arnett (1934 – 2025) Journalist and War Correspondent

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Zakir Hussain Meets Berklee

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joan Didion and Kurt Vonnegut Had Something to Say. We Have It on Tape

From The New York Times:

Tom Wolfe was a fast talker. Eudora Welty had a musical Southern drawl. Kurt Vonnegut’s jokes got belly laughs.

Tom Wolfe was a fast talker. Eudora Welty had a musical Southern drawl. Kurt Vonnegut’s jokes got belly laughs.

Each of these authors once spoke to audiences at the 92nd Street Y Unterberg Poetry Center in New York City, which has hosted some of the most celebrated writers of the past several generations, from Isaac Asimov to Anaïs Nin and Kazuo Ishiguro to Margaret Atwood. Now, the Poetry Center has digitized audio recordings of its literary events stretching back to 1949 — hundreds of which have never been released before — in a collection that offers a glimpse into history and a taste of what the writers themselves were like in public.

In 1965, for example, the year before he became consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress, James Dickey complained that his 14-year-old son had acquired a taste for rock ’n’ roll and a transistor radio. The sound of electric guitars had taken over his house. He was joined onstage that night by the poet Theodore Weiss, but it could have been Truman Capote, Joseph Heller or Adrienne Rich, who also visited the Poetry Center over the years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, December 19, 2025

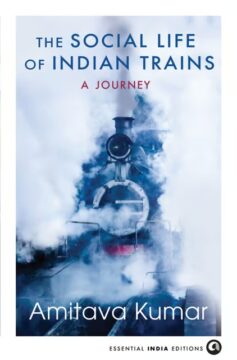

On Amitava Kumar’s “The Social Life of Indian Trains”

Eshan Sharma at The Wire:

Amitava Kumar has long occupied a distinctive place in contemporary English writing. His work resists easy classification, blurring the boundaries between fiction, memoir, reportage, history and critique.

Amitava Kumar has long occupied a distinctive place in contemporary English writing. His work resists easy classification, blurring the boundaries between fiction, memoir, reportage, history and critique.

With its stark white cover and a painting of a train in blue, perhaps suggestive of an accumulation of all the colours, lives and histories that animate his earlier work, he is now out with The Social Life of Indian Trains. This new book deals with something that we have come to take for granted: the railways.

Trains have been an inseparable part of our lives. Since childhood, I have travelled in bogies of every kind – unreserved, sleeper, second AC, first AC. If anything binds this subcontinental country together, it’s the railways, far more than cricket and films. Many lives depend on it: from those who work, to those who travel long distances to get to work. For some, it’s routine, for others, it’s a lifeline, and for many, still, it’s a wonder they’ve never experienced. More than being a part of our claimed identity, the history of trains has been a strange reminder of colonialism, a time we fantasise about erasing from our collective memory.

Given how integral the railways are to a nation’s life, they naturally find their way into popular culture, from literature to cinema.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

AI is transforming the economy — understanding its impact requires both data and imagination

Daniel Björkegren in Nature:

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

Given the high stakes, many researchers and policymakers are increasingly attempting to precisely quantify the causal impact of AI through natural experiments and randomized controlled trials. In such studies, one group gains access to an AI tool while another continues under normal conditions; other factors are held fixed. Researchers can then analyse outcomes such as productivity, satisfaction and learning.

Yet, when applied to AI, this type of evidence faces two challenges.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Tour of London in the 1700s

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

After Ruining a Treasured Water Resource, Iran Is Drying Up

Fred Pearce at Yale Environment 360:

More than international sanctions, more than its stifling theocracy, more than recent bombardment by Israel and the U.S. — Iran’s greatest current existential crisis is what hydrologists are calling its rapidly approaching “water bankruptcy.”

More than international sanctions, more than its stifling theocracy, more than recent bombardment by Israel and the U.S. — Iran’s greatest current existential crisis is what hydrologists are calling its rapidly approaching “water bankruptcy.”

It is a crisis that has a sad origin, they say: the destruction and abandonment of tens of thousands of ancient tunnels for sustainably tapping underground water, known as qanats, that were once the envy of the arid world. But calls for the Iranian government to restore qanats and recharge the underground water reserves that once sustained them are falling on deaf ears.

After a fifth year of extreme drought, Iran’s long-running water crisis reached unprecedented levels in November. The country’s president, Masoud Pezeshkian, warned that Iran had “no choice” but to move its capital away from arid Tehran, which now has a population of about 10 million, to wetter coastal regions — a project that would take decades and has a price estimated by analysts at potentially $100 billion.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

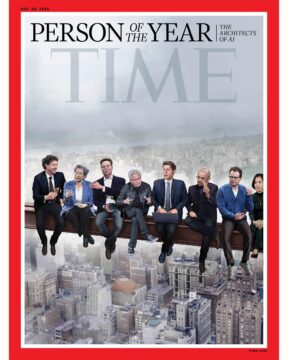

The Architects of AI Are TIME’s 2025 Person of the Year

From Time Magazine:

Jensen Huang needs a moment.

Jensen Huang needs a moment.

The CEO of Nvidia enters a cavernous studio at the company’s Bay Area headquarters and hunches over a table, his head bowed. At 62, the world’s eighth richest man is compact, polished, and known among colleagues for his quick temper as well as his visionary leadership. Right now, he looks exhausted. As he stands silently, it’s hard to know if he’s about to erupt or collapse. Then someone puts on a Spotify playlist and the stirring chords of Aerosmith’s “Dream On” fill the room. Huang puts on his trademark black leather jacket and appears to transform, donning not just the uniform, but also the body language and optimism befitting one of the foremost leaders of the artificial intelligence revolution.

Still, he’s got to be tired. Not too long ago, the former engineer ran a successful but semi-obscure outfit that specialized in graphics processors for video games. Today, Nvidia is the most valuable company in the world, thanks to a near-monopoly on the advanced chips powering an AI boom that is transforming the planet. Memes depict Nvidia as Atlas, holding the stock market on its shoulders. More than just a corporate juggernaut, Nvidia also has become an instrument of statecraft, operating at the nexus of advanced technology, diplomacy, and geopolitics. “You’re taking over the world, Jensen,” President Donald Trump, now a regular late-night phone buddy, told Huang during a recent state visit to the United Kingdom.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Newly discovered link between traumatic brain injury in children and epigenetic changes

From The Conversation:

A newly discovered biological signal in the blood could help health care teams and researchers better understand how children respond to brain injuries at the cellular level, according to our research in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

A newly discovered biological signal in the blood could help health care teams and researchers better understand how children respond to brain injuries at the cellular level, according to our research in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

In the future, this information could help clinicians identify children who need more tailored follow-up care after a traumatic brain injury. As part of our work as a nurse scientist and neuropsychologist studying traumatic brain injury, we wanted to look for biological markers inside cells that might help explain why some children recover smoothly after brain injury while others struggle. To do this, we focused on DNA, the instruction manual of cells. DNA is organized into regions called genes, each of which codes for proteins that carry out different functions like repairing tissues. While your DNA generally stays the same throughout your life, it can sometimes collect small chemical changes called epigenetic modifications. These changes act like dimmer switches, turning genes up or down without changing the underlying code. In general, dialing up the activity of a gene increases production of the protein it codes for, while dialing down the gene decreases production of that protein.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

The Children of the Poor

What shall I give my children? who are poor,

Who are adjudged the leastwise of the land,

Who are my sweetest lepers, who demand

No velvet and no velvety velour;

But who have begged me for a brisk contour,

Crying that they are quasi, contraband

Because unfinished, graven by a hand

Less the Angelic, admirable or sure.

My hand is stuffed with mode, design, device.

But I lack access to my proper stone.

And plenitude of plan shall not suffice

Not grief, nor love shall be enough alone

to ratify my little halves who bear

Across an autumn freezing everywhere.

by Gwendolyn Brooks

from Poet’s Choice

Time Life Books, 1962

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.