Chauncey Devega in Salon:

As you have been repeatedly reminded in recent days, one year ago, thousands of Donald Trump’s followers launched a lethal attack on the U.S. Capitol as part of a larger coup attempt whose obvious goal was to overturn America’s multiracial democracy and install their Great Leader as de facto dictator. Several people would died during the Capitol assault. More than 150 police officers and other law enforcement agents were injured.

As you have been repeatedly reminded in recent days, one year ago, thousands of Donald Trump’s followers launched a lethal attack on the U.S. Capitol as part of a larger coup attempt whose obvious goal was to overturn America’s multiracial democracy and install their Great Leader as de facto dictator. Several people would died during the Capitol assault. More than 150 police officers and other law enforcement agents were injured.

Many in Trump’s attack force were armed, including with guns. Explosives were found nearby, with other deadly weapons cached not far away. It’s a mistake to call Trump’s attack force a “mob” or to describe them as engaging in a “riot.” Knowingly or not, they were part of a coordinated effort to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election and overthrow American democracy.

In the year since then, we have begun to learn the scale of the larger fascist plot against democracy: It was nationwide, and conducted both by legal and extralegal means. At moments, a military coup appeared possible. Fox News and other right-wing propagandists systematically lied about the coup attempt, both as it was occurring and ever since. Right-wing street thugs and militias were activated. At least 1,000 Republican public officials were involved in planning and coordinating the coup, including members of Congress who volunteered to help facilitate a nullification of the 2020 election and a potential government takeover. There were detailed step-by-step plans as to how Vice President Mike Pence, in conjunction with Republican officials on the federal and state level, would reject the people’s will and keep Donald Trump in power.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

That hagiography can make a whole generation of listeners and griot consumers delusional or silly with lopsided obsession, but in the aftermath of Dilla’s time on the planet, the hero worship that bloomed felt more like a call to rigor and self-mastery. Dilla renewed a whole era’s trust in its ability to sound how it felt to be alive, to sound real and not like someone hoping to get famous off a gimmick. Our collective faith in singular greatness, like that of John Coltrane or Duke Ellington or Miles Davis or Billie Holiday, was renewed by Dilla. Dilla Time, the book, gives us a precise map of the influence we were trying to unravel then, and explains why it felt like mundane time had officially ended for a while. Mistakes were “thrilling to James,” Charnas writes. “They reminded him of messy house parties, and the interminable rehearsals of his childhood, and the discord of musical devotion in the sanctuary of Vernon Chapel, the unity made from the chaos of humans interacting.”

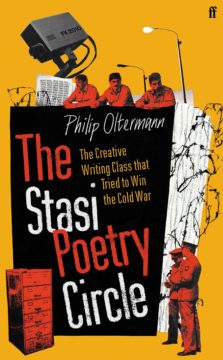

That hagiography can make a whole generation of listeners and griot consumers delusional or silly with lopsided obsession, but in the aftermath of Dilla’s time on the planet, the hero worship that bloomed felt more like a call to rigor and self-mastery. Dilla renewed a whole era’s trust in its ability to sound how it felt to be alive, to sound real and not like someone hoping to get famous off a gimmick. Our collective faith in singular greatness, like that of John Coltrane or Duke Ellington or Miles Davis or Billie Holiday, was renewed by Dilla. Dilla Time, the book, gives us a precise map of the influence we were trying to unravel then, and explains why it felt like mundane time had officially ended for a while. Mistakes were “thrilling to James,” Charnas writes. “They reminded him of messy house parties, and the interminable rehearsals of his childhood, and the discord of musical devotion in the sanctuary of Vernon Chapel, the unity made from the chaos of humans interacting.” Philip Oltermann’s engrossing The Stasi

Philip Oltermann’s engrossing The Stasi  What’s exceptional about the film’s use of the tune is that it is a love song sung under duress, not for courtship but to appease the whims of a leopard named Baby and an equally unpredictable woman (Hepburn is as much a principle of chaos as any wild creature). The song must be performed in the exact style and pace that accommodates the leopard’s movements: a harried and desperate version when Baby wants to jump out of the car; a few dawdling, absent-minded phrases once he’s safely on the estate.

What’s exceptional about the film’s use of the tune is that it is a love song sung under duress, not for courtship but to appease the whims of a leopard named Baby and an equally unpredictable woman (Hepburn is as much a principle of chaos as any wild creature). The song must be performed in the exact style and pace that accommodates the leopard’s movements: a harried and desperate version when Baby wants to jump out of the car; a few dawdling, absent-minded phrases once he’s safely on the estate. It was the second month of lockdown and the spring stretched before me like Arabic ice cream. My dad announced that he would be out all day, so I put two tabs of acid in a water bottle and headed out to the garden. A perfect time to pretend to enjoy solitude and figure out the riddles of the universe. I pulled out a big picnic blanket, sat beneath the shade of a young apple tree and waited for the new blooms of the cactus flower to speak.

It was the second month of lockdown and the spring stretched before me like Arabic ice cream. My dad announced that he would be out all day, so I put two tabs of acid in a water bottle and headed out to the garden. A perfect time to pretend to enjoy solitude and figure out the riddles of the universe. I pulled out a big picnic blanket, sat beneath the shade of a young apple tree and waited for the new blooms of the cactus flower to speak.

Wages have been stagnant for most Americans for decades. Inequality has increased sharply. Globalization and technology have enriched some, but also fueled job losses and impoverished communities.

Wages have been stagnant for most Americans for decades. Inequality has increased sharply. Globalization and technology have enriched some, but also fueled job losses and impoverished communities.

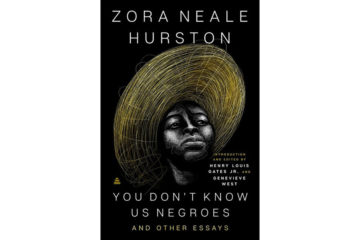

“Negro folklore is not a thing of the past,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote. “It is still in the making.”

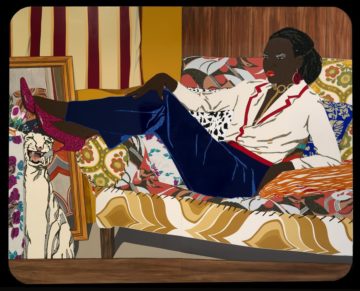

“Negro folklore is not a thing of the past,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote. “It is still in the making.” SAAM: SAAM’s website and physical spaces hold artworks and resources aplenty to take a deep dive into the presence and impact of African American artists on our world. In honor of Black History Month, here are a few of our favorite videos of artists speaking about their life, work, and inspiration.

SAAM: SAAM’s website and physical spaces hold artworks and resources aplenty to take a deep dive into the presence and impact of African American artists on our world. In honor of Black History Month, here are a few of our favorite videos of artists speaking about their life, work, and inspiration. Central banks have started reacting to inflation. In February, the Bank of England

Central banks have started reacting to inflation. In February, the Bank of England  Scientists say that urine diversion would have huge environmental and public-health benefits if deployed on a large scale around the world. That’s in part because urine is rich in nutrients that, instead of polluting water bodies, could go towards fertilizing crops or feed into industrial processes. According to Simha’s estimates, humans produce enough urine to replace about one-quarter of current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers worldwide; it also contains potassium and many micronutrients (see ‘What’s in urine’). On top of that, not flushing urine down the drain could save vast amounts of water and reduce some of the strain on ageing and overloaded sewer systems.

Scientists say that urine diversion would have huge environmental and public-health benefits if deployed on a large scale around the world. That’s in part because urine is rich in nutrients that, instead of polluting water bodies, could go towards fertilizing crops or feed into industrial processes. According to Simha’s estimates, humans produce enough urine to replace about one-quarter of current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers worldwide; it also contains potassium and many micronutrients (see ‘What’s in urine’). On top of that, not flushing urine down the drain could save vast amounts of water and reduce some of the strain on ageing and overloaded sewer systems. Artificial intelligence is everywhere around us. Deep-learning algorithms are used to classify images, suggest songs to us, and even to drive cars. But the quest to build truly “human” artificial intelligence is still coming up short. Gary Marcus argues that this is not an accident: the features that make neural networks so powerful also prevent them from developing a robust common-sense view of the world. He advocates combining these techniques with a more symbolic approach to constructing AI algorithms.

Artificial intelligence is everywhere around us. Deep-learning algorithms are used to classify images, suggest songs to us, and even to drive cars. But the quest to build truly “human” artificial intelligence is still coming up short. Gary Marcus argues that this is not an accident: the features that make neural networks so powerful also prevent them from developing a robust common-sense view of the world. He advocates combining these techniques with a more symbolic approach to constructing AI algorithms. A few decades ago the Stanford professor Ronald Howard

A few decades ago the Stanford professor Ronald Howard

T

T One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.”

One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.” Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled.

Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled.