John Rodden in American Purpose:

The end of 2021 witnessed an unusual literary event: the bicentennials of two geniuses of modern fiction. They were arguably the leading novelists of their respective countries: the Russian Fyodor Dostoevsky (November 11) and the Frenchman Gustave Flaubert (December 12). No conclusive biographical evidence exists that Dostoevsky ever read Madame Bovary (1857) or anything else by Flaubert. The reverse is certainly true: Flaubert knew no Russian, while Dostoevsky was little known in France until after he died in 1881, a year after Flaubert’s own death.

The end of 2021 witnessed an unusual literary event: the bicentennials of two geniuses of modern fiction. They were arguably the leading novelists of their respective countries: the Russian Fyodor Dostoevsky (November 11) and the Frenchman Gustave Flaubert (December 12). No conclusive biographical evidence exists that Dostoevsky ever read Madame Bovary (1857) or anything else by Flaubert. The reverse is certainly true: Flaubert knew no Russian, while Dostoevsky was little known in France until after he died in 1881, a year after Flaubert’s own death.

Still, the coincidence of the bicentennial anniversaries of their births provides an occasion to explore the fascinating similarities between the two writers within the enormous continent of their differences. Otherwise, no one would ever think to pair two authors so dissimilar as the punctilious, perfectionistic exemplar of French prose and the chaotic, disordered genius of the Russian novel. Indeed: not even the recent passing of their dual bicentennial prompted scholarly reflection on their resemblances and dissimilitudes, which says as much about academic overspecialization as it does about the two authors.

More here.

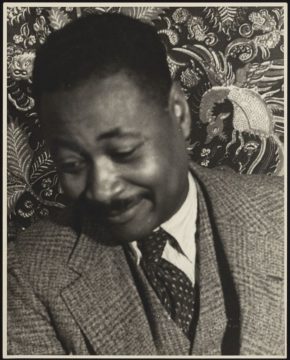

One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.”

One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.” Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled.

Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled. The

The  Misperceptions threaten to warp mass opinion and public policy on controversial issues in politics, science, and health. What explains the prevalence and persistence of these false and unsupported beliefs, which seem to be genuinely held by many people? Though limits on cognitive resources and attention play an important role, many of the most destructive misperceptions arise in domains where individuals have weak incentives to hold accurate beliefs and strong directional motivations to endorse beliefs that are consistent with a group identity such as partisanship. These tendencies are often exploited by elites who frequently create and amplify misperceptions to influence elections and public policy. Though evidence is lacking for claims of a “post-truth” era, changes in the speed with which false information travels and the extent to which it can find receptive audiences require new approaches to counter misinformation. Reducing the propagation and influence of false claims will require further efforts to inoculate people in advance of exposure (for example, media literacy), debunk false claims that are already salient or widespread (for example, fact-checking), reduce the prevalence of low-quality information (for example, changing social media algorithms), and discourage elites from promoting false information (for example, strengthening reputational sanctions).

Misperceptions threaten to warp mass opinion and public policy on controversial issues in politics, science, and health. What explains the prevalence and persistence of these false and unsupported beliefs, which seem to be genuinely held by many people? Though limits on cognitive resources and attention play an important role, many of the most destructive misperceptions arise in domains where individuals have weak incentives to hold accurate beliefs and strong directional motivations to endorse beliefs that are consistent with a group identity such as partisanship. These tendencies are often exploited by elites who frequently create and amplify misperceptions to influence elections and public policy. Though evidence is lacking for claims of a “post-truth” era, changes in the speed with which false information travels and the extent to which it can find receptive audiences require new approaches to counter misinformation. Reducing the propagation and influence of false claims will require further efforts to inoculate people in advance of exposure (for example, media literacy), debunk false claims that are already salient or widespread (for example, fact-checking), reduce the prevalence of low-quality information (for example, changing social media algorithms), and discourage elites from promoting false information (for example, strengthening reputational sanctions). In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

T

T Each Valentine’s Day, when I see images of the chubby winged god Cupid taking aim with his bow and arrow at his unsuspecting victims, I take refuge in my training as

Each Valentine’s Day, when I see images of the chubby winged god Cupid taking aim with his bow and arrow at his unsuspecting victims, I take refuge in my training as  Even a mild case of COVID-19 can increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular problems for at least a year after diagnosis, a new study

Even a mild case of COVID-19 can increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular problems for at least a year after diagnosis, a new study Some time in the tense winter of 1983, when Nato forces rehearsed a nuclear endgame to the Cold War so realistic that Soviet counter-intelligence briefly suspected it to be a cover for a real attack, a Stasi officer read out a stream-of-consciousness poem to a fellow intelligence operatives inside a heavily fortified compound in East Berlin.

Some time in the tense winter of 1983, when Nato forces rehearsed a nuclear endgame to the Cold War so realistic that Soviet counter-intelligence briefly suspected it to be a cover for a real attack, a Stasi officer read out a stream-of-consciousness poem to a fellow intelligence operatives inside a heavily fortified compound in East Berlin. De Francesco’s book is a fascinating historical examination of the charlatan figure that remains valid. Drawing on a variety of historical sources, de Francesco traces this path through early modern Europe, dwelling on alchemists, worm doctors, magnetizers, prestidigitators, and mountebanks. Individuals making an appearance include long-forgotten gold-makers like Leopold Thurneißer and Marco Bragadino, purported revenants like the Count of St. Germain, self-styled healers like Doctor Eisenbarth and James Graham, magicians like Jacob Philadelphia, and occultists like the Count Alessandro di Cagliostro. De Francesco, who sometimes comes across like a phenomenological sociologist in the tradition of Walter Benjamin or Siegfried Kracauer rather than an art historian, manages to distill the traits and behaviors of all these historical figures to an archetype.

De Francesco’s book is a fascinating historical examination of the charlatan figure that remains valid. Drawing on a variety of historical sources, de Francesco traces this path through early modern Europe, dwelling on alchemists, worm doctors, magnetizers, prestidigitators, and mountebanks. Individuals making an appearance include long-forgotten gold-makers like Leopold Thurneißer and Marco Bragadino, purported revenants like the Count of St. Germain, self-styled healers like Doctor Eisenbarth and James Graham, magicians like Jacob Philadelphia, and occultists like the Count Alessandro di Cagliostro. De Francesco, who sometimes comes across like a phenomenological sociologist in the tradition of Walter Benjamin or Siegfried Kracauer rather than an art historian, manages to distill the traits and behaviors of all these historical figures to an archetype. Gary Shteyngart has quietly become one of the most talented comic writers working in English today. More or less uniquely, apart maybe from bits of Zadie Smith, he’s even funny on the subject of identity. He’s also good on both Tom Wolfe’s ‘right – BAM! – now’ and J G Ballard’s ‘next five minutes’, having trained his lens on the brutal carnival of post-Soviet Russia in Absurdistan, the impact of tech on the mating habits of youngish Americans in Super Sad True Love Story and the fallout of the financial crisis of 2008 in Lake Success. If all that were not enough, he’s an unusually acute observer of a certain strain of male sexual anguish that some of his predecessors might have treated with an indulgence bordering on mysticism, but which most of his contemporaries now seem to view as little more than an abstract social problem or a handy plot device.

Gary Shteyngart has quietly become one of the most talented comic writers working in English today. More or less uniquely, apart maybe from bits of Zadie Smith, he’s even funny on the subject of identity. He’s also good on both Tom Wolfe’s ‘right – BAM! – now’ and J G Ballard’s ‘next five minutes’, having trained his lens on the brutal carnival of post-Soviet Russia in Absurdistan, the impact of tech on the mating habits of youngish Americans in Super Sad True Love Story and the fallout of the financial crisis of 2008 in Lake Success. If all that were not enough, he’s an unusually acute observer of a certain strain of male sexual anguish that some of his predecessors might have treated with an indulgence bordering on mysticism, but which most of his contemporaries now seem to view as little more than an abstract social problem or a handy plot device.

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection.

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection. On a Wednesday morning in January,

On a Wednesday morning in January,  My friend Agnes Callard

My friend Agnes Callard