Leanne Ogasawara, and artwork by Morgan Fisher, in Kyoto Journal (republished here):

1.

Back in the Tang dynasty, it was the heart that mattered. Thinking too much, philosophers warned, will only give you a headache. This fact was supported by the finest investigations of Chinese physicians and theologians who urged people to “still their hearts” and “empty their minds” in order to achieve liberation from suffering.

But Chinese Buddhists of the 7th century had a big problem to solve. One that would require some heavy-duty thinking.

How to translate abstract philosophical terms from Sanskrit –a language with an extraordinarily rich epistemological and ontological lexicon– into Chinese, a language poor in abstract vocabulary.

Words had to be invented. And it wouldn’t be easy, for how can a translator know if a translation is correct if they don’t have access to the original text?

It was to this task that Xuanzang, the Buddhist monk and translator extraordinaire devoted his life.

2.

2.

One of the core texts of Mahayana Buddhism, the Heart Sutra scarcely fills up a page of writing. In English, it is barely 400 words long. In Chinese, a mere 260 characters. A relatively new text, it was written down a thousand years after the Shakyamuni Buddha attained Nirvana. Quickly becoming one of the most widely studied and recited texts in the Mahayana world, the Heart Sutra is known for the way it pulls the epistemological rug out from beneath our feet. The sutra defies summarization. But its core message is that the outer world is illusory. Nothing is real.

But also, nothing is not real.

Ripping the veil off our preconceived notions, the sutra challenges our understanding of… well, of everything. Legend has it that several of Buddha’s followers became so perplexed upon first reading it that they suffered heart palpitations!

Even now, two millennia later, people feel confused by the notion that

FORM IS EMPTINESS, EMPTINESS IS FORM色不異空。空不異色。

It’s a slippery slope notion that attempts to explain a state of existence where nothing comes into being independently. (Got that?) The Chinese language could not cope. And the English language still struggles, as well.

For example, how to translate the Sanskrit term sunyata (emptiness, voidness zero)? Chinese translators had to proceed with great caution.

Avoiding the obvious choice, conveying negativity in Chinese: no/not/nothing (無), instead translators employed the Chinese word for “sky” (空), for this is suggestive of the “ethers”– like yin and yang– of mist and water, and of energy.

It is “emptiness depending on matter” and “matter depending on emptiness.”

Looking out your window, you realize the sky is not “nothing” or “void.” Rather, it is a boundless and boundary-less sphere. The perfect place for birds to fly and clouds to form. A generative space– and this is why some scholars suggest that a better English version of the Chinese translation is:

FORM IS BOUNDLESSNESS, BOUNDLESSNESS IS FORM.

Inseparable. Indivisible. Non- duality.

3.

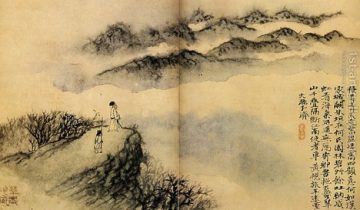

Imagine a Chinese landscape painting.

A gentleman-scholar is gazing out across a landscape filled with mist and sky.

There are mountains in the near distance, but the picture is mainly emptiness. The man almost disappears into the empty space. It is a landscape painting. But I would prefer to call it an inner landscape. As if the mind of the viewer, by mirroring the emptiness of the landscape, is thereby able to convey a world in constant flux in the workings of his own mind. Because mountains could not be conceived of without water and mist, the Buddhism- infused landscapes of China and Japan are often filled with a lot of empty space.

Heart is full in inverse relation to an empty mind

Being in the world=the world in being

Emptiness is energy

Invisible energy is visible matter

Yes, e=mc2

Even the cosmic vacuum is full of dark energy…

4.

4.

Divided from the rest of the empire by tall mountains and deep valleys, the Kingdom of Shu 蜀 has long been a place of exile, where emperors and kings sent those in disfavor. When the Sui dynasty collapsed in 618, countless numbers of China’s famed scholar-artists traveled there as well– either forced or in self-exile. Living in rustic huts, these scholar-artists composed some of the finest poetry and calligraphy in Chinese history.

Among these exiles was Xuanzang, who at 16 years of age was forced to flee the capital of Chang’an with his brother. The two young monks made their way to Chengdu, in the Kingdom of Shu. Here Xuanzang first came into contact with the Heart Sutra. Meeting a monk who was sick and hungry, he fed and clothed him, and by way of thanks this monk taught Xuanzang the Heart Sutra.

Like the reflective gentleman-scholar in the Chinese painting, surrounded by everything-nothingness, Xuanzang was now a thinker, and he had become concerned about certain discrepancies he had found in religious texts. Many Buddhist sutras and commentaries had been brought from India and translated into Chinese by that time, but Xuanzang understood that the competing interpretations pointed to the real possibility that Chinese monks (himself included!) were not understanding Buddhism in the same as the way Indians and Central Asians understood it. He therefore committed to joining the rank of religious pilgrims before and after him and set off to India, where he would study the texts with teachers in the original languages. All this in the hope of attaining real knowledge and deeper truth, on his “Journey to the West.”

5.

5.

Descartes famously began with the idea that “I think therefore I am.” From this idea of mind as the basis of reality, he tentatively derived the outer world as well. There is mind and there is matter. Spirit and substance. And this dualistic way of viewing existence has dominated Western philosophy ever since.

The Heart Sutra launches this philosophical stand into somersaults~~~

Body is mind, mind is body…

One cannot be derived from the other since both are inter-dependent.

Everything is interrelated and constantly changing.

Everything is everything else.

The Sanskrit term emptiness (空) becomes a double zero. A double negation. It is the zero that renders everything infinite. A zero that is perfect fullness. Zero over zero ( 0 / 0 =) is infinity. It is:

No eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind

No shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling, no thought

No this, no that, no nothing, no everything

No path, no heart

6.

In Nara, Yakushi Temple has an octagonal hall dedicated to Ganjo Sanzoin (as Xuanzang is known in Japan). The hall contains fragments of Xuanzang’s relic bones. These were apparently brought back from China by imperial Japanese soldiers stationed in Nanjing in 1942). Above the entrance, there is a sign that reads “No East” (不東) to remind people of the monk’s strong commitment of heart (決心) to not take even one step back toward home until he had achieved his mission.

And what a mission it was.

Some people consider Xuanzang to be the greatest traveler of all time. Marco Polo perhaps journeyed further in terms of distance—but, well, that was about 450 years later and things were more comfortable then. More importantly, while Polo traveled for reasons of wealth and fame, Xuanzang traveled to find the Truth– to understand the nature of reality, not just for himself– but for the sake of all sentient beings.

Passing through the Anxi Jade Gate in 627, Xuanzang broke Chinese law by leaving China proper. Traveling west along the Silk Road, he visited many of the ancient Buddhist kingdoms that dotted the path around the edges of the Taklamakam desert. He would make it as far as Afghanistan, where he left record of seeing the great statues of Bamiyan. Then he would turn south to India. He almost didn’t make it to India, so intent was the devout Buddhist King of Turfan to keep the pilgrim living in his kingdom he tried to hold the monk hostage. Rather than from any ill-will, the King quite simply could not bear to let such a stimulating conversationalist and brilliant debater leave his realm.

You can hardly blame him, right?

Along the way, Xuanzang was robbed and almost murdered several times, facing great danger again and again. Even his trusty helper turned against him at knifepoint. But Xuanzang had his talisman. In reciting the Heart Sutra whenever he was in danger, he kept his resolve and managed to finally make it to Nalanda University, near present day Patna. This was the great center of Buddhist learning of the time. Xuanzang stayed many years, studying Buddhist philosophy, logic and Sanskrit with the greatest Buddhist teachers of the day. Returning to China eighteen years later, he hauled a library of books back with him and spent the remainder of his days teaching and translating.

7.

Xuanzang’s new translations revolutionized the Chinese Buddhist world. By this time, the Emperor had forgiven the monk’s unauthorized departure for India and pledged his full support. Some twenty monks were assigned to the translation process—and what a process it was!

Xuanzang first translated the Sanskrit text into spoken Chinese. Then a scribe would work with Xuanzang to transcribe the oral Chinese into the most appropriate Chinese ideograms. Xuanzang’s deep experience with India and Indian Buddhism led to manifold revisions, striving for authenticity. For example, prior to his journey, the land of India was referred to in Chinese as 天竺 (tianzhu), which came from the Chinese transliteration of the Old Persian Hinduka (Hindu). The ideograms were changed to 印度 (Yìndù), the default word for “India” in China to this day.

The earlier word for India, 天竺 (tianzhu), is still with us today in the modern renditions of the classic Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West. This novelized account of Xuanzang’s epic journey was made famous in English with the publication of Arthur Waley’s abridged translation, titled Monkey, which followed the monk on his legendary trip to the land of tianzhu (tenjiku in Japanese) with three disciples, including an impetuous monkey with extraordinary magical powers.

After the phonetic step described above, a Sanskrit reader would then confirm the accuracy of Xuanzang’s Chinese translation. In the final step, a team member double-checked the ideograms. Many changes were made to further improve the authenticity of the translation. A prominent example was dropping the earlier term for “sattva” (眾生), meaning “multitude of lives or sentient being” and using 有情, which refers to feelings; this would be read as a more precise term when connoting “a sentient being who possesses feelings,” 有情 [眾生]. “Sattva” in the Mahayana tradition is a general term for all sentient beings in contrast to Buddhas, and Xuanzang’s re-translation of this term probably better reflects Mahayana understanding of this core Buddhist concept.

Because of this meticulously attentive multi-step process, Xuanzang’s translations are considered to be exceedingly accurate. He was not only the greatest Chinese translator of Sanskrit Buddhist texts of his time, but his translations continue to play a major role to this day—none more than the Heart Sutra, for which he is renowned.

8.

8.

Xuanzang’s version of the Heart Sutra is probably the single-most chanted mantra on earth.

The Sanskrit term for “heart” hridaya, means “body, mind, heart….” But one other possible meaning for hridaya is “incantation.” This has led some scholars to suggest that the sutra was always thought to be fundamentally a mantra. Even now, it is chanted in Buddhist temples daily around the world. In Japan, where it is known as known as the Hannya Shingyo, it is particularly prominent in Rinzai sects of Zen Buddhism. But from Tibet to Japan, the Heart Sutra is chanted, read and written with ink and brush as part of the meditation practices of the devout.

The short sutra itself ends with a Great Mantra, explained to be:

The most illuminating mantra,

the highest mantra,

a mantra beyond compare,

the True Wisdom that has the power

to put an end to all kinds of suffering.

This concludes with the incantation

Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!

Meaning, “Gone, gone, everyone gone to the other shore, awakening, Amen.”

Or as Allen Ginsberg translated it:

Gone gone totally gone totally gone over the top, wakened mind, So, ah!

In 2014, Thich Nhat Hanh, in order to improve Western understanding of the Heart Sutra, created a new English translation. He wanted to ensure that no one would ever again misunderstand the sutra in terms of the English word “emptiness.” For the “zero” or “emptiness” of sunyata is not a nihilistic teaching, he says. The new title should emphasize the essence of the teaching as one of “inter-being,” “No-Self,” “the Middle Way,” “singleness,” and “aimlessness:”

The Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore

We are all drowning in an ocean of samsara—of ego, of mis-understandings and mis-translations. If we commit to the Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya, “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom,” we can use this teaching as a lifeboat– or as Augustine said of Beauty, as “a plank amid the waves of the sea” to paddle toward the Other Shore of Nirvana.

9.

9.

Here’s a question: Are profound religious truths accessible to people without temple or teacher? Can they arrive in a flash?

Can something appear out of nothing?

Can truth strike a person like a lightning bolt in blue skies?

Do mountains smile when all beings open their eyes?

Pointing to a world beyond this one, a storehouse of Buddhist teachings has been passed down generation to generation.

These teachings are embedded in esoteric mandalas and statues of Bodhisattvas, and they are chanted by believers daily.

Wisdom beyond wisdom, this is the boundless mind.

That is the grace and beauty of Buddhism – its profound positivity – that each of us is capable, through individual study and practice, of grasping the ultimate reality and achieving liberation.

—-

This essay first appeared in Kyoto Journal 98 “Ma”

Thank you Jeffrey Kotyk and Dan Lusthaus for scholarly advice.

LEANNE OGASAWARA has worked as a translator from the Japanese for over

twenty years. Her translation work has included academic translation, poetry,

philosophy, and documentary film. She is a frequent contributor at 3 Quarks Daily.

MORGAN FISHER is an artist and musician based in Tokyo.

morgan-fisher.com