Mark Vendevelde in Financial Times:

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/7d9678e0-ab1b-11e8-89a1-e5de165fa619

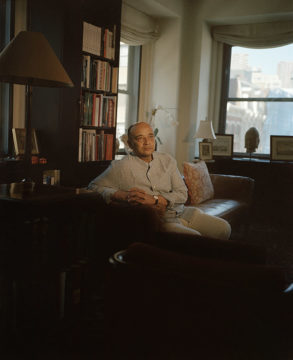

Kwame Anthony Appiah is a black, gay, American man who is descended from aristocrats and speaks English with one of those BBC accents you pick up at the better British schools. You probably think these facts tell you a certain amount about him. Highlight text Appiah, a professor of philosophy in New York, knows such badges matter — he has made a career studying concepts like blackness and gayness, social labels that guide us through humanity’s ungraspable diversity — but he wants you to know that most of what they signify is pure baloney. Consider race. Thomas Jefferson, often described as one the most enlightened of American thinkers, thought black people smelled worse than whites, required less sleep, had comparably good memories, but couldn’t master geometry. Today no one could count such outrageous views as enlightened; but as Appiah understood, they were the product of a time in which white colonialists had used the idea of an inferior race to justify mass exploitation. “The truth is that there are no races,” he declared in a 1985 essay that earned him fame among philosophers and social theorists, and notoriety among some of his African-American peers. “The ‘whites’ invented the Negroes in order to dominate them,” he later wrote in the award-winning essay collection In My Father’s House (1992).

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

What did the sensitivity readers say? And did I care? Of all the aspects of the

What did the sensitivity readers say? And did I care? Of all the aspects of the  Masayuki Nakahata has been waiting 35 years for a nearby star to explode.

Masayuki Nakahata has been waiting 35 years for a nearby star to explode. An increasing number of politicians and media analysts claim Putin may be mentally unstable, or that he is isolated in a bubble of yes-men who don’t warn him of dangers ahead. Many commentators say he is trying to restore the Soviet Union or recreate a Russian sphere of influence on his country’s borders, and that this week’s intrusion into eastern

An increasing number of politicians and media analysts claim Putin may be mentally unstable, or that he is isolated in a bubble of yes-men who don’t warn him of dangers ahead. Many commentators say he is trying to restore the Soviet Union or recreate a Russian sphere of influence on his country’s borders, and that this week’s intrusion into eastern  Two hundred thousand years ago, the earliest shared ancestors of every living human on Earth rested their feet at a verdant oasis in the middle of Africa’s

Two hundred thousand years ago, the earliest shared ancestors of every living human on Earth rested their feet at a verdant oasis in the middle of Africa’s  “I’m just trying to get authentically to that,” the actress Stephanie Berry told her director, Whitney White, as they stood in a spacious rehearsal room in the East Village in mid-January. They were working out a bit of business that might or might not end up in “On Sugarland,” Aleshea Harris’s third full-length play, which premières at New York Theatre Workshop on March 3rd. “On Sugarland” was inspired by “Philoctetes,” Sophocles’ play about an expert archer plagued by chronic pain and exiled because of the smell of a wound on his foot. (A snake bit him while he was walking on sacred ground; so much for hubris.) Sophocles’ character may be powerful and gifted, but he is also set apart by the stench of his difference. Eventually, the god Heracles promises to heal Philoctetes’ foot if he returns to Troy to fight in the Trojan War. This is the mythology that jump-starts Harris’s new play, which is itself about mythology: one myth being that, by serving your country, you are protecting your community and yourself; another being that love can vanquish pain.

“I’m just trying to get authentically to that,” the actress Stephanie Berry told her director, Whitney White, as they stood in a spacious rehearsal room in the East Village in mid-January. They were working out a bit of business that might or might not end up in “On Sugarland,” Aleshea Harris’s third full-length play, which premières at New York Theatre Workshop on March 3rd. “On Sugarland” was inspired by “Philoctetes,” Sophocles’ play about an expert archer plagued by chronic pain and exiled because of the smell of a wound on his foot. (A snake bit him while he was walking on sacred ground; so much for hubris.) Sophocles’ character may be powerful and gifted, but he is also set apart by the stench of his difference. Eventually, the god Heracles promises to heal Philoctetes’ foot if he returns to Troy to fight in the Trojan War. This is the mythology that jump-starts Harris’s new play, which is itself about mythology: one myth being that, by serving your country, you are protecting your community and yourself; another being that love can vanquish pain.

Since the Yale cognitive scientist Laurie Santos began teaching her class Psychology and the Good Life in 2018, it has become one of the school’s most popular courses. The first year the class was offered, nearly a quarter of the undergraduate student body enrolled. You could see that as a positive: all these young high-achievers looking to learn scientifically corroborated techniques for living a happier life. But you could also see something melancholy in the course’s popularity: all these young high-achievers looking for something they’ve lost, or never found. Either way, the desire to lead a more fulfilled life is hardly limited to young Ivy Leaguers, and Santos turned her course into a popular podcast series

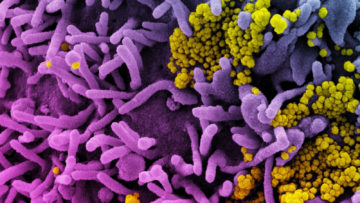

Since the Yale cognitive scientist Laurie Santos began teaching her class Psychology and the Good Life in 2018, it has become one of the school’s most popular courses. The first year the class was offered, nearly a quarter of the undergraduate student body enrolled. You could see that as a positive: all these young high-achievers looking to learn scientifically corroborated techniques for living a happier life. But you could also see something melancholy in the course’s popularity: all these young high-achievers looking for something they’ve lost, or never found. Either way, the desire to lead a more fulfilled life is hardly limited to young Ivy Leaguers, and Santos turned her course into a popular podcast series  In the ongoing struggle of SARS-CoV-2’s genes versus our wits, the virus that causes Covid-19 relentlessly probes human defenses with new genetic gambits. New variants of this coronavirus with increasing transmissibility have sprung up every few months, a scenario that is likely to continue.

In the ongoing struggle of SARS-CoV-2’s genes versus our wits, the virus that causes Covid-19 relentlessly probes human defenses with new genetic gambits. New variants of this coronavirus with increasing transmissibility have sprung up every few months, a scenario that is likely to continue.

Federer exercised an animal fascination over the children, and myself, that was different from that of Roddick or Murray or the others. This may have had something to do with fame, but many were too young for that. Like most great athletes, like Jordan, Kobe, Zidane, Messi, lions, etc., Federer is more fluid than those around him. His body and being appear to be extremely relaxed until the moment of movement, which is fast, smooth and has something lethal about it. What makes him so unreadable a player (he is famously difficult to anticipate) is this very relaxation, for it is tension that opponents can learn to read, whereas relaxation is illegible. No one arrives so perfectly on time for his meeting with the ball as Federer, not only never too late, but never too early, so that all the momentum of his arrival flows into the shot with what appears to be almost effortless violence. Most professionals do this approximately, often with lots of fine-tuning little steps at the last minute (right before impact, Nadal, for instance, takes a series of hunched mini-steps). Federer does it so exactly that his strides are long, which is only possible thanks to the unearthly sense he obviously has of where his body is in relation to everything, always.

Federer exercised an animal fascination over the children, and myself, that was different from that of Roddick or Murray or the others. This may have had something to do with fame, but many were too young for that. Like most great athletes, like Jordan, Kobe, Zidane, Messi, lions, etc., Federer is more fluid than those around him. His body and being appear to be extremely relaxed until the moment of movement, which is fast, smooth and has something lethal about it. What makes him so unreadable a player (he is famously difficult to anticipate) is this very relaxation, for it is tension that opponents can learn to read, whereas relaxation is illegible. No one arrives so perfectly on time for his meeting with the ball as Federer, not only never too late, but never too early, so that all the momentum of his arrival flows into the shot with what appears to be almost effortless violence. Most professionals do this approximately, often with lots of fine-tuning little steps at the last minute (right before impact, Nadal, for instance, takes a series of hunched mini-steps). Federer does it so exactly that his strides are long, which is only possible thanks to the unearthly sense he obviously has of where his body is in relation to everything, always. Last Sunday the host of a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body. The host was broadcasting from Washington, D.C., and I was seated in a remote studio on the Far West Side of Manhattan. A satellite closed the miles between us, but no machinery could close the gap between her world and the world for which I had been summoned to speak. When the host asked me about my body, her face faded from the screen, and was replaced by a scroll of words, written by me earlier that week.

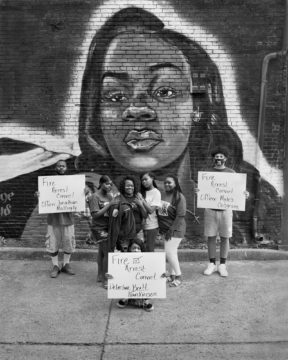

Last Sunday the host of a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body. The host was broadcasting from Washington, D.C., and I was seated in a remote studio on the Far West Side of Manhattan. A satellite closed the miles between us, but no machinery could close the gap between her world and the world for which I had been summoned to speak. When the host asked me about my body, her face faded from the screen, and was replaced by a scroll of words, written by me earlier that week. Kenny calls me in the middle of the night. He says, Somebody kicked in the door and shot Breonna. I am dead asleep. I don’t know what he’s talking about. I jump up. I get ready, and I rush over to her house. When I get there, the street’s just flooded with police—it’s a million of them. And there’s an officer at the end of the road, and I tell her who I am and that I need to get through there because something had happened to my daughter. She tells me I need to go to the hospital because there was two ambulances that came through, and the first took the officer and the second took whoever else was hurt. Of course I go down to the hospital, and I tell them why I am there. The lady looks up Breonna and doesn’t see her and says, Well, I don’t think she’s here yet. I wait for about almost two hours. The lady says, Well, ma’am, we don’t have any recollection of this person being on the way.

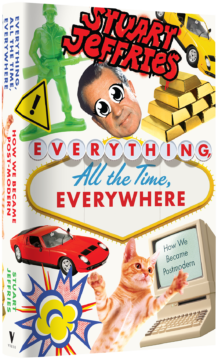

Kenny calls me in the middle of the night. He says, Somebody kicked in the door and shot Breonna. I am dead asleep. I don’t know what he’s talking about. I jump up. I get ready, and I rush over to her house. When I get there, the street’s just flooded with police—it’s a million of them. And there’s an officer at the end of the road, and I tell her who I am and that I need to get through there because something had happened to my daughter. She tells me I need to go to the hospital because there was two ambulances that came through, and the first took the officer and the second took whoever else was hurt. Of course I go down to the hospital, and I tell them why I am there. The lady looks up Breonna and doesn’t see her and says, Well, I don’t think she’s here yet. I wait for about almost two hours. The lady says, Well, ma’am, we don’t have any recollection of this person being on the way. We easily and often apply the label ‘postmodern’ to particular artworks, architecture, activities and ideas; it is harder to specify some common quality of postmodernism that they all share. Far more than other historical phases, ‘postmodernity’ seems almost to have been concocted by those who write about it. The term suggests an impossible realm – after the present yet somehow already present itself; the concept, judging by the copious literature on it, is precisely about imprecision and lack of essence, and better defined by what it is not. Jean-François Lyotard’s much-cited The Postmodern Condition (1979) diagnosed in it an absence of ‘grand narratives’ (Christianity, liberalism, Marxism), which have been abandoned due to lack of faith in the march of progress. We are left instead, in a Waste Land way, with fragments we have shored against our ruin. Now that modernism has exhausted outrage and authenticity, and been domesticated and canonised, all postmodern art and architecture can do is pastiche and appropriate earlier styles, blazoning their own lack of originality. A central principle of postmodernism is ‘intertextuality’, the notion that ‘any text is the absorption and transformation of any other’, in the words of Julia Kristeva.

We easily and often apply the label ‘postmodern’ to particular artworks, architecture, activities and ideas; it is harder to specify some common quality of postmodernism that they all share. Far more than other historical phases, ‘postmodernity’ seems almost to have been concocted by those who write about it. The term suggests an impossible realm – after the present yet somehow already present itself; the concept, judging by the copious literature on it, is precisely about imprecision and lack of essence, and better defined by what it is not. Jean-François Lyotard’s much-cited The Postmodern Condition (1979) diagnosed in it an absence of ‘grand narratives’ (Christianity, liberalism, Marxism), which have been abandoned due to lack of faith in the march of progress. We are left instead, in a Waste Land way, with fragments we have shored against our ruin. Now that modernism has exhausted outrage and authenticity, and been domesticated and canonised, all postmodern art and architecture can do is pastiche and appropriate earlier styles, blazoning their own lack of originality. A central principle of postmodernism is ‘intertextuality’, the notion that ‘any text is the absorption and transformation of any other’, in the words of Julia Kristeva.

Chekhov is easier to know and read than the other Russian giants. He doesn’t look big or talk big. He’s funny on purpose. He shows us how to read him; he quietly attunes us to place and situation. We observe more than judge his characters’ actions; we detect their mental and emotional states through their physical symptoms. Chekhov began his professional career as a writer while in medical school. Even as he imagined the agitations and disruptions and occasional explosions of his characters, he was always also a doctor. He describes what it feels like to fall in love, to be pregnant and to miscarry, to bully one’s children, to flutter about helplessly while seeking someone to love, to have typhus, to cringe with embarrassment over a bespattering sneeze, to blather like a professor, to be struck dumb by love, to beg for sympathy, to grieve, to menace the innocent, to be conscious of but prey to one’s weaknesses, to be overworked to the point of hallucinating, to be ruthless.

Chekhov is easier to know and read than the other Russian giants. He doesn’t look big or talk big. He’s funny on purpose. He shows us how to read him; he quietly attunes us to place and situation. We observe more than judge his characters’ actions; we detect their mental and emotional states through their physical symptoms. Chekhov began his professional career as a writer while in medical school. Even as he imagined the agitations and disruptions and occasional explosions of his characters, he was always also a doctor. He describes what it feels like to fall in love, to be pregnant and to miscarry, to bully one’s children, to flutter about helplessly while seeking someone to love, to have typhus, to cringe with embarrassment over a bespattering sneeze, to blather like a professor, to be struck dumb by love, to beg for sympathy, to grieve, to menace the innocent, to be conscious of but prey to one’s weaknesses, to be overworked to the point of hallucinating, to be ruthless.