Stanley Deser in Inference Review:

I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD Kenneth Clark’s Rede Lecture, delivered at Cambridge in 1970, on artists and writers as they grow old. He drew some surprising conclusions: the writers were less likely to carry on, whereas some of the greatest artists, Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt van Rijn, J. M. W. Turner, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, and in our day, Pablo Picasso and Jasper Johns, became, if anything, more productive and liberated from convention as they went into old age, despite the physical effort involved. Clark did not really give the whys of the old—in both senses—masters’ endurance as against the poets’ falling off.

I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD Kenneth Clark’s Rede Lecture, delivered at Cambridge in 1970, on artists and writers as they grow old. He drew some surprising conclusions: the writers were less likely to carry on, whereas some of the greatest artists, Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt van Rijn, J. M. W. Turner, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, and in our day, Pablo Picasso and Jasper Johns, became, if anything, more productive and liberated from convention as they went into old age, despite the physical effort involved. Clark did not really give the whys of the old—in both senses—masters’ endurance as against the poets’ falling off.

This led me to consider my own field: physics, mostly theoretical. Of course, Clark was an eminent art critic and historian, while I am only a geriatric working stiff, whose life as a researcher gives me a technical appreciation of my field. Physics has its historians, but if there are physics critics in the same sense as art critics, then I am, perhaps wrongly, unaware of them.

Physics’s greatest giants either died young, as did James Clerk Maxwell at age 48, or stopped meaningful work well before they died, as in the cases of Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Paul Dirac, and Max Born, or changed fields, like Erwin Schrödinger.

More here.

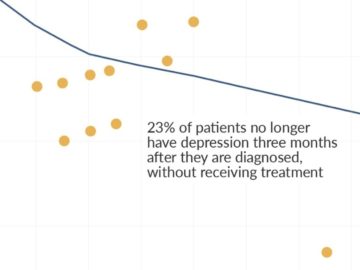

In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings.

In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings. In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions.

In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions. After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.”

After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.” Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements. Of constant fascination for me are the ways in which literature employs skin color to reveal character or drive narrative—especially if the fictional main character is white (which is almost always the case). Whether it is the horror of one drop of the mystical “black” blood, or signs of innate white superiority, or of deranged and excessive sexual power, the framing and the meaning of color are often the deciding factors. For the horror that the “one-drop” rule excites, there is no better guide than William Faulkner. What else haunts “The Sound and the Fury” or “Absalom, Absalom!”? Between the marital outrages incest and miscegenation, the latter (an old but useful term for “the mixing of races”) is obviously the more abhorrent. In much American literature, when plot requires a family crisis, nothing is more disgusting than mutual sexual congress between the races. It is the mutual aspect of these encounters that is rendered shocking, illegal, and repulsive. Unlike the rape of slaves, human choice or, God forbid, love receives wholesale condemnation. And for Faulkner they lead to murder.

Of constant fascination for me are the ways in which literature employs skin color to reveal character or drive narrative—especially if the fictional main character is white (which is almost always the case). Whether it is the horror of one drop of the mystical “black” blood, or signs of innate white superiority, or of deranged and excessive sexual power, the framing and the meaning of color are often the deciding factors. For the horror that the “one-drop” rule excites, there is no better guide than William Faulkner. What else haunts “The Sound and the Fury” or “Absalom, Absalom!”? Between the marital outrages incest and miscegenation, the latter (an old but useful term for “the mixing of races”) is obviously the more abhorrent. In much American literature, when plot requires a family crisis, nothing is more disgusting than mutual sexual congress between the races. It is the mutual aspect of these encounters that is rendered shocking, illegal, and repulsive. Unlike the rape of slaves, human choice or, God forbid, love receives wholesale condemnation. And for Faulkner they lead to murder. IN MAY OF 2012

IN MAY OF 2012 Many of Robinson’s twenty-one science-fiction novels are ecological in theme, and this coming summer he will publish “

Many of Robinson’s twenty-one science-fiction novels are ecological in theme, and this coming summer he will publish “ What the face mask is to American society, the essay is to American literature: deceptively slight, heroically versatile, centuries old but lately a subject of great interest — not because it’s doing anything new, but because everything else is falling apart.

What the face mask is to American society, the essay is to American literature: deceptively slight, heroically versatile, centuries old but lately a subject of great interest — not because it’s doing anything new, but because everything else is falling apart. A great deal of public discussion in recent weeks has suggested that “endemicity”—a state where the virus continues to circulate in the population like scores of other respiratory viruses, with more predictability albeit probably still with seasonal surges—is around the corner. The Europe office of the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently stated that the continent may be entering the “

A great deal of public discussion in recent weeks has suggested that “endemicity”—a state where the virus continues to circulate in the population like scores of other respiratory viruses, with more predictability albeit probably still with seasonal surges—is around the corner. The Europe office of the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently stated that the continent may be entering the “ During the first pandemic lockdowns, thousands of vivid dreams were suddenly shared across the internet and among friends. Though some of them had to do directly with COVID, many were simply intense and mysterious, in the way dreams often are. Yet for some reason, people felt newly impelled to convey them to others. The dreams were soon compiled into databases, written up in newspaper articles, and eventually integrated into scientific studies. This phenomenon may turn out to be a significant event in the history of the social imagination. For thousands of years, and in many cultures, talking about dreams has been considered hugely important. But in modernity, dreams have been regularly denigrated. In the mainstream, at least, they have been written off as superstitious, flighty, or boring. Then suddenly, in the pandemic, a great mass of people, mobilized across the internet, felt (at least for a few months) otherwise. There has probably never been such a sudden and expansive efflorescence of public dream sharing in modern history.

During the first pandemic lockdowns, thousands of vivid dreams were suddenly shared across the internet and among friends. Though some of them had to do directly with COVID, many were simply intense and mysterious, in the way dreams often are. Yet for some reason, people felt newly impelled to convey them to others. The dreams were soon compiled into databases, written up in newspaper articles, and eventually integrated into scientific studies. This phenomenon may turn out to be a significant event in the history of the social imagination. For thousands of years, and in many cultures, talking about dreams has been considered hugely important. But in modernity, dreams have been regularly denigrated. In the mainstream, at least, they have been written off as superstitious, flighty, or boring. Then suddenly, in the pandemic, a great mass of people, mobilized across the internet, felt (at least for a few months) otherwise. There has probably never been such a sudden and expansive efflorescence of public dream sharing in modern history.

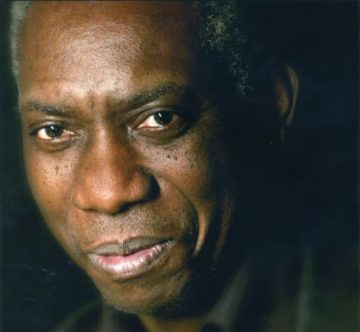

Shadow and Act contains Ralph Ellison’s real autobiography—in the form of essays and interviews—as distinguished from the symbolic version given in his splendid novel of 1952, Invisible Man Some of the twenty-odd items in it were written as early as 1942, and not all of them have been published before. One or two were rejected by liberal periodicals, apparently because Ellison insisted on saying that Negro American life was not everywhere as hellish or as inert or as devastated by hatred and self-hatred as it was sometimes alleged; it is not unlikely that liberal criticism will be equally impatient with this new book. Most of the pieces, were, however, written after Invisible Man and in part are a consequence of it. They may even help to explain the long gap of time between Ellison’s first novel and its much awaited successor. There have been other theories about this delay: for example, an obituary notice by Le Roi Jones who, in a recent summary of the supposedly lethal effect of America upon its Negro writers, referred to Ellison as “silenced and fidgeting away in some college.” But he has not been silent, much less silenced—by White America or anything else. The experiences of writing Invisible Man and of vaulting on his first try “over the parochial limits of most Negro fiction” (as Richard G. Stern says in an interview), and, as a result, of being written about as a literary and sociological phenomenon, combined with sheer compositional difficulties, seem to have driven Ellison to search out the truths of his own past. Inquiring into his experience, his literary and musical education, Ellison has come up with a number of clues to the fantastic fate of trying to be at the same time a writer, a Negro, an American, and a human being.

Shadow and Act contains Ralph Ellison’s real autobiography—in the form of essays and interviews—as distinguished from the symbolic version given in his splendid novel of 1952, Invisible Man Some of the twenty-odd items in it were written as early as 1942, and not all of them have been published before. One or two were rejected by liberal periodicals, apparently because Ellison insisted on saying that Negro American life was not everywhere as hellish or as inert or as devastated by hatred and self-hatred as it was sometimes alleged; it is not unlikely that liberal criticism will be equally impatient with this new book. Most of the pieces, were, however, written after Invisible Man and in part are a consequence of it. They may even help to explain the long gap of time between Ellison’s first novel and its much awaited successor. There have been other theories about this delay: for example, an obituary notice by Le Roi Jones who, in a recent summary of the supposedly lethal effect of America upon its Negro writers, referred to Ellison as “silenced and fidgeting away in some college.” But he has not been silent, much less silenced—by White America or anything else. The experiences of writing Invisible Man and of vaulting on his first try “over the parochial limits of most Negro fiction” (as Richard G. Stern says in an interview), and, as a result, of being written about as a literary and sociological phenomenon, combined with sheer compositional difficulties, seem to have driven Ellison to search out the truths of his own past. Inquiring into his experience, his literary and musical education, Ellison has come up with a number of clues to the fantastic fate of trying to be at the same time a writer, a Negro, an American, and a human being. In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.