Mordechai Rorvig in Quanta:

Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough.

Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough.

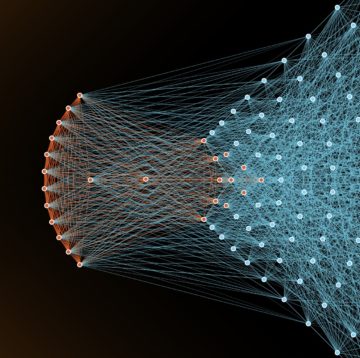

Not so for neural networks, the leading artificial intelligence systems for performing humanlike tasks. As they’ve gotten bigger, they have come to grasp more. This has been a surprise to onlookers. Fundamental mathematical results had suggested that networks should only need to be so big, but modern neural networks are commonly scaled up far beyond that predicted requirement — a situation known as overparameterization.

In a paper presented in December at NeurIPS, a leading conference, Sébastien Bubeck of Microsoft Research and Mark Sellke of Stanford University provided a new explanation for the mystery behind scaling’s success.

More here.

Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment.

Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment. The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

W

W Y

Y Laura Kipnis in LitHub:

Laura Kipnis in LitHub: Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books:

Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books: Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate:

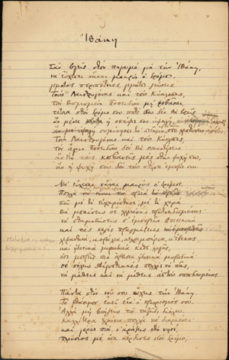

Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate: How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller.

How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller. In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

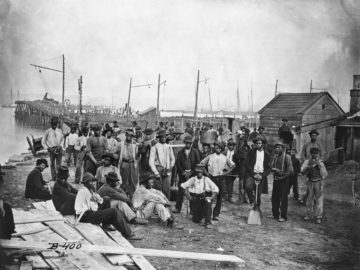

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or  “Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery.

“Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery. I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD

I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings.

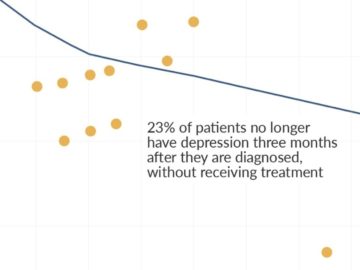

In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings.