Yiyun Li at the Paris Review:

Two moments in Graham Greene’s published life have often returned to me in the past twenty years. This may sound strange: an ideal reader should refrain from crossing the boundary between a writer’s work and his life. And yet it is inevitable: rarely does an author have the luxury of having no known biography. Greene, having written about his life and having had his life extensively written about by others, remains near when one reads his work—not insistently dominating or distracting, as some writers may prove to be, but as a presence often felt and at times caught by a side glance.

Two moments in Graham Greene’s published life have often returned to me in the past twenty years. This may sound strange: an ideal reader should refrain from crossing the boundary between a writer’s work and his life. And yet it is inevitable: rarely does an author have the luxury of having no known biography. Greene, having written about his life and having had his life extensively written about by others, remains near when one reads his work—not insistently dominating or distracting, as some writers may prove to be, but as a presence often felt and at times caught by a side glance.

The first moment appears in Greene’s memoir Ways of Escape. In a chapter about Brighton Rock, which Greene called a labour of love, he explains the original inspiration for the novel with a reminiscence about the first film he saw at age six—a silent film about a kitchen maid turned queen, with live music played offscreen—he writes, “Her march was accompanied by an old lady on a piano, but the tock-tock-tock of untuned wires stayed in my memory when other melodies faded … That was the kind of book I always wanted to write: the high romantic tale, capturing us in youth with hopes that prove illusions, to which we return again in age in order to escape the sad reality.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Yes, every fashionable conference has some panel on AI. Yes, social media is overrun with hypemen trying to alert their readers to the latest “mind-blowing” improvements of Grok or ChatGPT. But even as the maturation of AI technologies provides the inescapable background hum of our cultural moment, the mainstream outlets that pride themselves on their wisdom and erudition—even, in moments of particular self-regard, on their meaning-making mission—are lamentably failing to grapple with its epochal significance.

Yes, every fashionable conference has some panel on AI. Yes, social media is overrun with hypemen trying to alert their readers to the latest “mind-blowing” improvements of Grok or ChatGPT. But even as the maturation of AI technologies provides the inescapable background hum of our cultural moment, the mainstream outlets that pride themselves on their wisdom and erudition—even, in moments of particular self-regard, on their meaning-making mission—are lamentably failing to grapple with its epochal significance. The worst-case scenario of famine is currently playing out in the Gaza Strip.” These were the

The worst-case scenario of famine is currently playing out in the Gaza Strip.” These were the  A

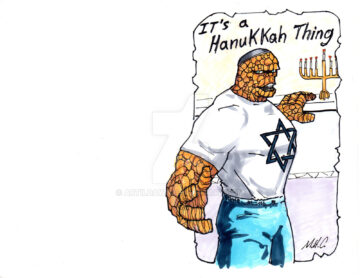

A IN 1975, JACK KIRBY, the “King of Comics” whose wildly kinetic art and sweeping visions had shaped the whole universe of Marvel Comics, sent a Hanukkah card to a friend, a young fan Kirby had met a few years earlier at a New York comics convention. At the time, Kirby had been living in Thousand Oaks, California, where he’d joined a Conservative synagogue, Temple Etz Chaim. An active temple member, Kirby occasionally read Torah portions at Shabbat services, visited the Hebrew School to demonstrate the art of drawing comics for the students, and later fulfilled a lifelong dream when he joined a congregational trip to Israel. So there was nothing remarkable about him sending a Hannukah card—except, that is, for

IN 1975, JACK KIRBY, the “King of Comics” whose wildly kinetic art and sweeping visions had shaped the whole universe of Marvel Comics, sent a Hanukkah card to a friend, a young fan Kirby had met a few years earlier at a New York comics convention. At the time, Kirby had been living in Thousand Oaks, California, where he’d joined a Conservative synagogue, Temple Etz Chaim. An active temple member, Kirby occasionally read Torah portions at Shabbat services, visited the Hebrew School to demonstrate the art of drawing comics for the students, and later fulfilled a lifelong dream when he joined a congregational trip to Israel. So there was nothing remarkable about him sending a Hannukah card—except, that is, for  There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be

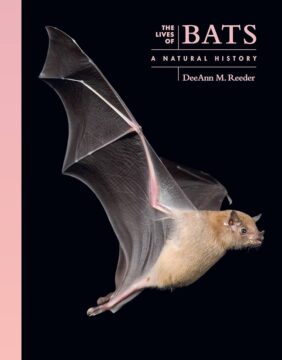

There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be  I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations.

I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations. “These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.”

“These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.” Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning

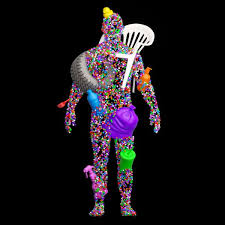

Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning  Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it.

Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it.