Michael Atkinson at The Current:

More than the films of any other genre, horror movies are the phenotypes of cultural anxiety—often, you can read the turbulence right on the skin, like hives. In Japan, a nation always rich with wild expressions of social stress, this phenomenon yielded two primary surges: the New Wave attack of the 1950s and ’60s, and the J-horror invasion starting in the late ’80s and ’90s. While these phases reflected different societal shifts, when you take the macro view, they come together to look like one big haunting.

More than the films of any other genre, horror movies are the phenotypes of cultural anxiety—often, you can read the turbulence right on the skin, like hives. In Japan, a nation always rich with wild expressions of social stress, this phenomenon yielded two primary surges: the New Wave attack of the 1950s and ’60s, and the J-horror invasion starting in the late ’80s and ’90s. While these phases reflected different societal shifts, when you take the macro view, they come together to look like one big haunting.

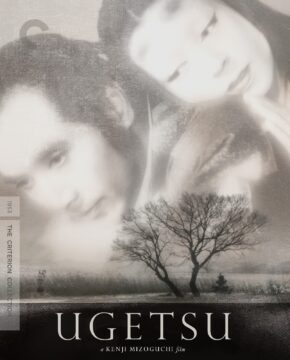

The New Wave horror films are primarily set in the broad swath of history stretching from the early feudal centuries to the Edo period. In America, the Old West is just for westerns, but in Japan, the medieval epoch has always been ripe for use in any genre or mode. Both eras were formative and have proven irresistible because they represent the evolution from semicivilized lawlessness to modernity (still, despite its massive mythology, the Old West, from the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 onward, stretched for maybe eighty-five years, while the Japanese had over half a millennium to play with). The history was always a fuming source of folktales, including kaidan (ghost stories), and that’s the boneyard the New Wave dug into; after the distinctly gentle ghostliness of Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), the most notable kaidan adaptations include Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964), Kuroneko (1968), and The Iron Crown (1972), as well as Nobuo Nakagawa’s The Ghost of Kasane (1957), Black Cat Mansion (1958), and The Ghost of Yotsuya (1959); Masaki Kobayashi’s lavish Kwaidan (1964); and Kimiyoshi Yasuda and Yoshiyuki Kuroda’s Yokai Monsters trilogy (1968–69).

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.