The Such Thing As the Ridiculous Question

Where are you from???

…….. When I say ancestors, let’s be clear:

…….. I mean slaves. I’m talkin’ Tennessee

…….. cotton & Louisiana suga. I mean grave

dirt. I come from homes & marriages

named after the same type of weapon –

all it takes is a shotgun to know

I’m Black. I don’t got no secrets

a bullet ain’t told. Danger see me

& sit down somewhere.

I’m a direct descendant of last words

& first punches. I got stolen blood.

My complexion is America’s

darkest hour. You can trace my great

great great great great grandmother back

to a scream. I bet somewhere it’s a haint

with my eyes. My last name is a protest;

a brick through a window in a house

my bones built. One million

scabs from one scar.

Heavy is the hand that held

the whip. Black is the back that carried this

country & when this country’s palm gets

an itch, I become money. You give this country

an inch & it will take a freedom. You can’t talk slick

to this legacy of oiled scalps. You can’t spit

on my race & call it reign. I sound like my mama now,

who sound like her mama who sound like her mama who

sound like her mama, who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama, who sound like a scream.

& that’s why I’m so loud, remember? You wanna know

where I’m from? Easy. Open a wound

& watch it heal.

by Siaara Freeman

from Split This Rock

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

While often citing American critic and screenwriter James Agee as a model for her emotional and intellectual engagement with the cinema, Kael claimed that she “was more influenced . . . by literary critics, such as R. P. Blackmur.”

While often citing American critic and screenwriter James Agee as a model for her emotional and intellectual engagement with the cinema, Kael claimed that she “was more influenced . . . by literary critics, such as R. P. Blackmur.” Among the earliest forms of visual imagery are, of course, the cave paintings of Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa, which often feature images of animals, hunting scenes, dancing people, and handprints that may signify the presence of a specific creator. Although we can’t be absolutely sure what the images were meant to convey, cave painting is a familiar enough case of the impulse of ancient artists to create significant images that seem aimed at replicating and perhaps even controlling an otherwise fleeting reality. Capturing the image of an animal, for example, perhaps meant freezing it in time and thereby magically ensuring good hunting.

Among the earliest forms of visual imagery are, of course, the cave paintings of Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa, which often feature images of animals, hunting scenes, dancing people, and handprints that may signify the presence of a specific creator. Although we can’t be absolutely sure what the images were meant to convey, cave painting is a familiar enough case of the impulse of ancient artists to create significant images that seem aimed at replicating and perhaps even controlling an otherwise fleeting reality. Capturing the image of an animal, for example, perhaps meant freezing it in time and thereby magically ensuring good hunting. I rarely eat fruit. But because I’ve been taken in by healthy living campaigns, I occasionally find myself buying a half kilo of pears or apples or grapes. Why these expensive imports? I think it’s because they were once totally unattainable to me, and now that I can afford them—while I still can afford them—I bring them home and put them in my fridge as a little act of revenge. Rarer still, I might buy a bunch of bananas, just because they’re right there in between the cassava and tempeh at the vegetable peddler’s stall. But I never buy papayas, watermelon, or mangoes. I grew up surrounded by papaya trees and I simply cannot accept a business transaction in their name. Papayas are obtained in two ways: asking or just taking. It’s very hard for me to entertain any other option. And watermelon reminds me of my childhood. From when I was ten until I was fifteen, my mother tried to support us by selling them. She was a very kind woman, but a terrible merchant, and so watermelons bring me back to a time in my childhood that I’d rather forget—grudgingly waking before dawn and trudging to market shouldering two heavy baskets, my mother’s tears over her financial losses and the other burdens she had to bear. Watermelons were my first foray into critical philosophy: Why does the sweet, red watermelon, with no sour bite, sell for so much less than citrus? I’ll eat one now and then, but I won’t buy a fruit that brings back such bad memories.

I rarely eat fruit. But because I’ve been taken in by healthy living campaigns, I occasionally find myself buying a half kilo of pears or apples or grapes. Why these expensive imports? I think it’s because they were once totally unattainable to me, and now that I can afford them—while I still can afford them—I bring them home and put them in my fridge as a little act of revenge. Rarer still, I might buy a bunch of bananas, just because they’re right there in between the cassava and tempeh at the vegetable peddler’s stall. But I never buy papayas, watermelon, or mangoes. I grew up surrounded by papaya trees and I simply cannot accept a business transaction in their name. Papayas are obtained in two ways: asking or just taking. It’s very hard for me to entertain any other option. And watermelon reminds me of my childhood. From when I was ten until I was fifteen, my mother tried to support us by selling them. She was a very kind woman, but a terrible merchant, and so watermelons bring me back to a time in my childhood that I’d rather forget—grudgingly waking before dawn and trudging to market shouldering two heavy baskets, my mother’s tears over her financial losses and the other burdens she had to bear. Watermelons were my first foray into critical philosophy: Why does the sweet, red watermelon, with no sour bite, sell for so much less than citrus? I’ll eat one now and then, but I won’t buy a fruit that brings back such bad memories. As the tech industry spends and spends,

As the tech industry spends and spends,  There are two ways to decarbonize: 1) degrowth, and 2) green energy. None of the proponents of degrowth are asking China to stop growing its economy

There are two ways to decarbonize: 1) degrowth, and 2) green energy. None of the proponents of degrowth are asking China to stop growing its economy B

B It’s easy to take safe drinking water for granted. In most developed countries, access to safe water takes a simple flip of a kitchen tap or a run to the grocery store. But over

It’s easy to take safe drinking water for granted. In most developed countries, access to safe water takes a simple flip of a kitchen tap or a run to the grocery store. But over  The idea of

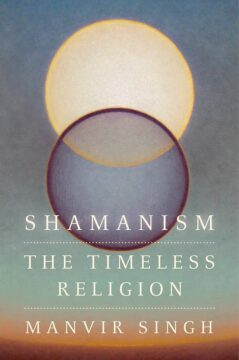

The idea of  Shamanism defines religion as a yin-yang battle between its “shamanic” and “institutional” elements. The chaotic forces of individual prophecy, possession, and inspiration give rise to formal religious rituals and doctrines, which in turn constrict those same forces. Singh argues for an extreme broadening of what “shamanism” refers to. It encompasses not only Siberian and Pan-American Indigenous practices, whose similarities (and potentially shared Asian origins) have long been acknowledged, but also a broad and much more transcultural spectrum of phenomena including charisma, possession, mounting, glossolalia, dream journeying, catching the holy spirit, trance, and other things. These phenomena all involve inducing special states of consciousness in the “shaman,” their audience, or both, in order to communicate with the beyond: to speak with gods and ancestors, to see the future, or to discover one’s spirit animal.

Shamanism defines religion as a yin-yang battle between its “shamanic” and “institutional” elements. The chaotic forces of individual prophecy, possession, and inspiration give rise to formal religious rituals and doctrines, which in turn constrict those same forces. Singh argues for an extreme broadening of what “shamanism” refers to. It encompasses not only Siberian and Pan-American Indigenous practices, whose similarities (and potentially shared Asian origins) have long been acknowledged, but also a broad and much more transcultural spectrum of phenomena including charisma, possession, mounting, glossolalia, dream journeying, catching the holy spirit, trance, and other things. These phenomena all involve inducing special states of consciousness in the “shaman,” their audience, or both, in order to communicate with the beyond: to speak with gods and ancestors, to see the future, or to discover one’s spirit animal. I

I  S

S In Urban Fortunes, their foundational work on the economies of cities, urban theorists John Logan and Harvey Molotch argue that the people running American cities no longer care about affordability, a city’s ability to educate children, or the happiness and health of its residents; rather, they are only interested the amount of money a city is able to generate. This focus is not the result of a philosophical bug that’s somehow spread to the brains of city managers everywhere. People such as Richard Florida make the city-as-business philosophy seem appealing, but there’s something bigger going on. Logan and Molotch argue that the city-as-growth-machine is an inherent feature of late capitalism in the United States. Cities, more than being places for people to live, have become ways to produce, manage, attract, and extract capital.

In Urban Fortunes, their foundational work on the economies of cities, urban theorists John Logan and Harvey Molotch argue that the people running American cities no longer care about affordability, a city’s ability to educate children, or the happiness and health of its residents; rather, they are only interested the amount of money a city is able to generate. This focus is not the result of a philosophical bug that’s somehow spread to the brains of city managers everywhere. People such as Richard Florida make the city-as-business philosophy seem appealing, but there’s something bigger going on. Logan and Molotch argue that the city-as-growth-machine is an inherent feature of late capitalism in the United States. Cities, more than being places for people to live, have become ways to produce, manage, attract, and extract capital. A

A