Gerald Howard at n+1:

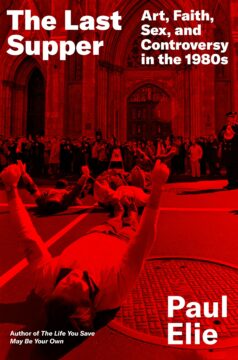

Paul Elie remembers things differently and far more deeply. A cradle Catholic and still an observant one, he has over the years carved out an admirable niche for himself as the thinking believer and village explainer of those hard to fathom people for the readers of the Times, the New Yorker, and similar publications. (He had a first-rate take on Pope Leo’s papacy up on the latter’s website within a day of the new pontiff’s ascent.) The Life You Save May Be Your Own, Elie’s group biography of four prominent midcentury Catholic writers and intellectuals (Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, Walker Percy, and Thomas Merton), is one of the best achieved examples of a tricky genre. He manages to make the fact of his faith very clear while remaining uninsistent about it—unlike, say, the profoundly annoying Ross Douthat, who can’t and won’t shut up about his conversion to Catholicism (as strongly as many of us wish he would). As a critic and historian Elie has clarity, depth, and range—qualities that serve him well as he navigates the stormy and turbid high/low waters of his chosen decade’s cultural output.

Paul Elie remembers things differently and far more deeply. A cradle Catholic and still an observant one, he has over the years carved out an admirable niche for himself as the thinking believer and village explainer of those hard to fathom people for the readers of the Times, the New Yorker, and similar publications. (He had a first-rate take on Pope Leo’s papacy up on the latter’s website within a day of the new pontiff’s ascent.) The Life You Save May Be Your Own, Elie’s group biography of four prominent midcentury Catholic writers and intellectuals (Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, Walker Percy, and Thomas Merton), is one of the best achieved examples of a tricky genre. He manages to make the fact of his faith very clear while remaining uninsistent about it—unlike, say, the profoundly annoying Ross Douthat, who can’t and won’t shut up about his conversion to Catholicism (as strongly as many of us wish he would). As a critic and historian Elie has clarity, depth, and range—qualities that serve him well as he navigates the stormy and turbid high/low waters of his chosen decade’s cultural output.

Elie is an unusual figure in the secular publications and the lists of the publishers he writes for because he takes religion and its manifestations as primary—not simply as an area of culture (film, music, lifestyle, and so on) treated as just another subject for investigation.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Could a Philly Cheesesteak joint actually

Could a Philly Cheesesteak joint actually  In a provocative study published in Nature Communications late last year, the neuroscientist Nikolay Kukushkin and his mentor Thomas J. Carew at New York University showed that human kidney cells growing in a dish can

In a provocative study published in Nature Communications late last year, the neuroscientist Nikolay Kukushkin and his mentor Thomas J. Carew at New York University showed that human kidney cells growing in a dish can  The NRA was founded in 1871. For most of its long history, it was an apolitical organization of sportsmen that promoted marksmanship and safety training so duck hunters wouldn’t shoot themselves in the toes. In the Eisenhower era, the NRA’s motto, emblazoned over its front door was “Firearms Safety Education, Marksmanship Training, Shooting for Recreation.”

The NRA was founded in 1871. For most of its long history, it was an apolitical organization of sportsmen that promoted marksmanship and safety training so duck hunters wouldn’t shoot themselves in the toes. In the Eisenhower era, the NRA’s motto, emblazoned over its front door was “Firearms Safety Education, Marksmanship Training, Shooting for Recreation.” The story of human evolution has undergone a distinct feminisation in recent decades. Or, rather, an equalisation: a much-needed rebalancing after 150 years during which, we were told, everything was driven by males strutting, brawling and shagging, with females just along for the ride. This reckoning has finally arrived at language. The origins of our species’ exceptional communication skills constitutes one of the more nebulous zones of the larger evolutionary narrative, because many of the bits of the human anatomy that allow us to communicate – notably the brain and the vocal tract – are soft and don’t fossilise. The linguistic societies of Paris and London even banned talk of evolution around 1870, and the subject only made a timid comeback about a century later. Plenty of theories have been tossed into the evidentiary void since then, mainly by men, but now evolutionary biologist Madeleine Beekman, of the University of Sydney, has turned her female gaze on the problem.

The story of human evolution has undergone a distinct feminisation in recent decades. Or, rather, an equalisation: a much-needed rebalancing after 150 years during which, we were told, everything was driven by males strutting, brawling and shagging, with females just along for the ride. This reckoning has finally arrived at language. The origins of our species’ exceptional communication skills constitutes one of the more nebulous zones of the larger evolutionary narrative, because many of the bits of the human anatomy that allow us to communicate – notably the brain and the vocal tract – are soft and don’t fossilise. The linguistic societies of Paris and London even banned talk of evolution around 1870, and the subject only made a timid comeback about a century later. Plenty of theories have been tossed into the evidentiary void since then, mainly by men, but now evolutionary biologist Madeleine Beekman, of the University of Sydney, has turned her female gaze on the problem. In an iconic scene in the cyberpunk classic

In an iconic scene in the cyberpunk classic  Alone figure stands at the edge of the Universe and hurls a spear into the unknown, only to find the edge wasn’t an edge after all. A demon tells a chronically ill person that every moment of their life — every high, every hardship — will repeat forever, exactly as it is. A 16-year-old boy tries to travel alongside a beam of light, hoping to catch up, but no matter how fast he goes, it never slows. Someone is offered the chance to live in a simulated paradise, but there’s a catch: Once inside, they’ll forget it isn’t real. And a human falls in love with a consciousness that has no body, no boundaries, and no need for them.

Alone figure stands at the edge of the Universe and hurls a spear into the unknown, only to find the edge wasn’t an edge after all. A demon tells a chronically ill person that every moment of their life — every high, every hardship — will repeat forever, exactly as it is. A 16-year-old boy tries to travel alongside a beam of light, hoping to catch up, but no matter how fast he goes, it never slows. Someone is offered the chance to live in a simulated paradise, but there’s a catch: Once inside, they’ll forget it isn’t real. And a human falls in love with a consciousness that has no body, no boundaries, and no need for them. At the heart of all life is a code. Our cells use it to turn the information in our DNA into proteins. So do maple trees. So do hammerhead sharks. So do shiitake mushrooms. Except for some minor variations, the genetic code is universal.

At the heart of all life is a code. Our cells use it to turn the information in our DNA into proteins. So do maple trees. So do hammerhead sharks. So do shiitake mushrooms. Except for some minor variations, the genetic code is universal. While Netanyahu and Trump bombed Iran, dozens of prominent Iranian Americans

While Netanyahu and Trump bombed Iran, dozens of prominent Iranian Americans  T

T S

S Prisons are American tourist attractions, and criminals who become fugitives or inmates our outlaw heroes—Al Capone, Alcatraz, Charles Manson, Sing Sing, Angola, Luigi Mangione, O. J. Simpson, Diddy, né Sean Combs. A collective underdog fetish means that the image of a civilian outwitting, outrunning, or confronting “the man” is enough to negate his trespasses. Maybe achieving the apotheosis of success in the United States requires becoming a convict, being threatened with or facing real incarceration and exile, doing time, paying dues, and making a grand comeback. At that finale you can sell that story to restore your fortunes, dignity, and maverick glory. Combs is the latest public figure to go from celebrated to disgraced to tentatively redeemed in some eyes by a show trial and the masculine compulsion to cheer when men get away with terrorizing women. The rapper Jay Electronica stood outside of the courtroom with his two Great Danes on the day the verdict was delivered, and announced, “I’m just here supporting my brother.” He looked half-ashamed, half-deviant about it, like he was both courting and afraid of backlash. Others call Diddy’s comeuppance a legal lynching, insinuating he’s a survivor of a because-he’s-black character assassination, since other powerful, abusive men have yet to be held accountable. It’s a truly American malfunction, this belief that the once oppressed should have the freedom to become as evil and ruthlessly decadent as their oppressors. This is what is sold to the public as prestige, and imitations of it exist at every stratum. With this in mind, Diddy’s story could be construed as a bootstraps tale—from Harlem to Howard to Hollywood endings. His recent downward spiral might be just another buoy, one that will help him ascend anew.

Prisons are American tourist attractions, and criminals who become fugitives or inmates our outlaw heroes—Al Capone, Alcatraz, Charles Manson, Sing Sing, Angola, Luigi Mangione, O. J. Simpson, Diddy, né Sean Combs. A collective underdog fetish means that the image of a civilian outwitting, outrunning, or confronting “the man” is enough to negate his trespasses. Maybe achieving the apotheosis of success in the United States requires becoming a convict, being threatened with or facing real incarceration and exile, doing time, paying dues, and making a grand comeback. At that finale you can sell that story to restore your fortunes, dignity, and maverick glory. Combs is the latest public figure to go from celebrated to disgraced to tentatively redeemed in some eyes by a show trial and the masculine compulsion to cheer when men get away with terrorizing women. The rapper Jay Electronica stood outside of the courtroom with his two Great Danes on the day the verdict was delivered, and announced, “I’m just here supporting my brother.” He looked half-ashamed, half-deviant about it, like he was both courting and afraid of backlash. Others call Diddy’s comeuppance a legal lynching, insinuating he’s a survivor of a because-he’s-black character assassination, since other powerful, abusive men have yet to be held accountable. It’s a truly American malfunction, this belief that the once oppressed should have the freedom to become as evil and ruthlessly decadent as their oppressors. This is what is sold to the public as prestige, and imitations of it exist at every stratum. With this in mind, Diddy’s story could be construed as a bootstraps tale—from Harlem to Howard to Hollywood endings. His recent downward spiral might be just another buoy, one that will help him ascend anew. One morning in 2009, Jacqueline Tabler woke up with the solution to a laboratory problem that had been plaguing her for months. She got out of bed, grabbed her notebook, and started sketching out an experiment that had come to her in a dream.

One morning in 2009, Jacqueline Tabler woke up with the solution to a laboratory problem that had been plaguing her for months. She got out of bed, grabbed her notebook, and started sketching out an experiment that had come to her in a dream. O

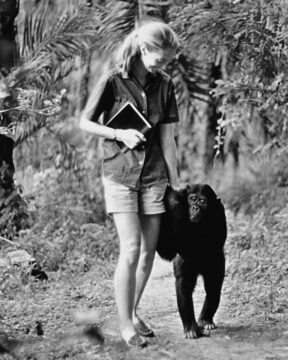

O On 14 July 1960, 65 years ago this week, a young English woman with no formal scientific background or qualifications stepped off a boat at the Gombe Stream Game Reserve in Tanzania to begin what would become a pioneering study of wild chimpanzees. Her discoveries would not just revolutionise our understanding of animal behaviour but reshape the way we define ourselves as

On 14 July 1960, 65 years ago this week, a young English woman with no formal scientific background or qualifications stepped off a boat at the Gombe Stream Game Reserve in Tanzania to begin what would become a pioneering study of wild chimpanzees. Her discoveries would not just revolutionise our understanding of animal behaviour but reshape the way we define ourselves as