Diana Lind in the Washington Post:

There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be time spent alone and sedentary, triggering two of Americans’ biggest mental and physical health problems — social isolation and lack of exercise.

There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be time spent alone and sedentary, triggering two of Americans’ biggest mental and physical health problems — social isolation and lack of exercise.

Screens surely explain some of our turn inward, but not all of it. For example, men are spending a record 100 minutes per day on household activities, including a 50 percent increase in time spent cooking since 2003. And if our phones, tablets, and video games are as insidious as they’re often portrayed, then part of the solution needs to be finding real-life environments and activities that can compete for attention with apps and streaming services at home.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations.

I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations. “These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.”

“These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.” Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning

Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning  Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it.

Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it. T

T Her book design itself seems an exercise in branding. Only the word “Melania” on the cover. Nothing else, indicating not just fame but a sort of stardom, a woman known by only one name like singers Madonna and Beyoncé or, more fitting here, models Iman and Twiggy. Or a First Lady like Jackie, who may have been the only post-World War II president’s wife who could have published an autobiography with the same design and gotten away with it. One-third of this short book is made up of photographs of Melania, appropriate, I suppose, for a book about a model, but perhaps also a way for her to hide in plain sight, so to speak, to avoid having to talk about things she does not wish to talk about.

Her book design itself seems an exercise in branding. Only the word “Melania” on the cover. Nothing else, indicating not just fame but a sort of stardom, a woman known by only one name like singers Madonna and Beyoncé or, more fitting here, models Iman and Twiggy. Or a First Lady like Jackie, who may have been the only post-World War II president’s wife who could have published an autobiography with the same design and gotten away with it. One-third of this short book is made up of photographs of Melania, appropriate, I suppose, for a book about a model, but perhaps also a way for her to hide in plain sight, so to speak, to avoid having to talk about things she does not wish to talk about. Claims that computing underlies physical reality are hard to prove or disprove, but a clear-cut case for computation in nature came to light far earlier than Wheeler’s “it from bit” hypothesis. John von Neumann, an accomplished mathematical physicist and another founding figure of computer science, discovered a profound link between computing and biology as far back as

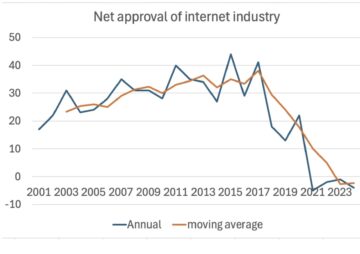

Claims that computing underlies physical reality are hard to prove or disprove, but a clear-cut case for computation in nature came to light far earlier than Wheeler’s “it from bit” hypothesis. John von Neumann, an accomplished mathematical physicist and another founding figure of computer science, discovered a profound link between computing and biology as far back as  In fact, the basic logic of enshittification — in which businesses start out being very good to their customers, then switch to ruthless exploitation — applies to any business characterized by network effects. It may go under different names like “penetration pricing,” but the logic is the same.

In fact, the basic logic of enshittification — in which businesses start out being very good to their customers, then switch to ruthless exploitation — applies to any business characterized by network effects. It may go under different names like “penetration pricing,” but the logic is the same. S

S I

I  W

W