Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian:

Samuel Pepys’s diary, which covers 1660 to 1669, is regarded as one of the great classic texts in the English language. Words spill out of Pepys – 1.25m of them – as he bustles around London, building a successful career as a naval administrator while navigating the double trauma of the plague and the Great Fire of London. Historians have long gone to the diary for details of middle-class life during the mid‑17th century: the seamy streets, the watermen, the taverns and, as Pepys moves up the greasy pole, the court and the king. Best of all is his eye for the picturesque detail: the way, for instance, on the morning of 4 September 1666, as fire licks around his house, Pepys buries a choice parmesan cheese in the garden with the intention of keeping it safe.

Samuel Pepys’s diary, which covers 1660 to 1669, is regarded as one of the great classic texts in the English language. Words spill out of Pepys – 1.25m of them – as he bustles around London, building a successful career as a naval administrator while navigating the double trauma of the plague and the Great Fire of London. Historians have long gone to the diary for details of middle-class life during the mid‑17th century: the seamy streets, the watermen, the taverns and, as Pepys moves up the greasy pole, the court and the king. Best of all is his eye for the picturesque detail: the way, for instance, on the morning of 4 September 1666, as fire licks around his house, Pepys buries a choice parmesan cheese in the garden with the intention of keeping it safe.

Not all of the diary is in English, though. Quite a lot of it is in French (or rather Franglais), Latin, Spanish and a curious mashup of all three. Pepys increasingly resorted to this home-brewed polyglot whenever the subject of sex came up, which was often.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

You know you’re in a Cynthia Ozick short story when the wind is merciless and the leaves have dropped. It may already be snowing. In “Bloodshed,” we are greeted by the “icy scenes” that a gun-toting rationalist sees from a Greyhound bus on his way to a “town of the hasidim” outside New York City, where he is ultimately shamed and disarmed by a local rebbe. In “The Biographer’s Hat,” snowflakes adorn the fur collar of a crooked biographer who mouches off a proofreader and persuades her to falsely insert herself into his subject’s history. “A Mercenary” concludes with the haunting vision of a man lying dead “under the stone-white hanging stars of Poland…. Against the stones and under the snow.”

You know you’re in a Cynthia Ozick short story when the wind is merciless and the leaves have dropped. It may already be snowing. In “Bloodshed,” we are greeted by the “icy scenes” that a gun-toting rationalist sees from a Greyhound bus on his way to a “town of the hasidim” outside New York City, where he is ultimately shamed and disarmed by a local rebbe. In “The Biographer’s Hat,” snowflakes adorn the fur collar of a crooked biographer who mouches off a proofreader and persuades her to falsely insert herself into his subject’s history. “A Mercenary” concludes with the haunting vision of a man lying dead “under the stone-white hanging stars of Poland…. Against the stones and under the snow.” It would be easy to insist that LLMs are just objects, obviously. As an engineer I get it—it doesn’t matter how convincing the human affectations are, underneath the conversational interface is still nothing but data, algorithms, and matrix multiplication. Any projection of subject-hood is clearly just anthropomorphic nonsense.

It would be easy to insist that LLMs are just objects, obviously. As an engineer I get it—it doesn’t matter how convincing the human affectations are, underneath the conversational interface is still nothing but data, algorithms, and matrix multiplication. Any projection of subject-hood is clearly just anthropomorphic nonsense.  T

T Post-independence, Pakistan faced deep identity dilemmas. Should it be a secular Muslim-majority state or an Islamic theocracy? The 1971 secession of East Pakistan into Bangladesh exposed the fragility of religious unity in the face of linguistic and ethnic differences. As Akeel Bilgrami (Secularism, Identity and Enchantment, 2014) observes, the premise of a single Muslim identity was flawed when confronted with South Asia’s diversity.

Post-independence, Pakistan faced deep identity dilemmas. Should it be a secular Muslim-majority state or an Islamic theocracy? The 1971 secession of East Pakistan into Bangladesh exposed the fragility of religious unity in the face of linguistic and ethnic differences. As Akeel Bilgrami (Secularism, Identity and Enchantment, 2014) observes, the premise of a single Muslim identity was flawed when confronted with South Asia’s diversity. This much we know: Smartphones are making us dumber. Compelling essays suggest we

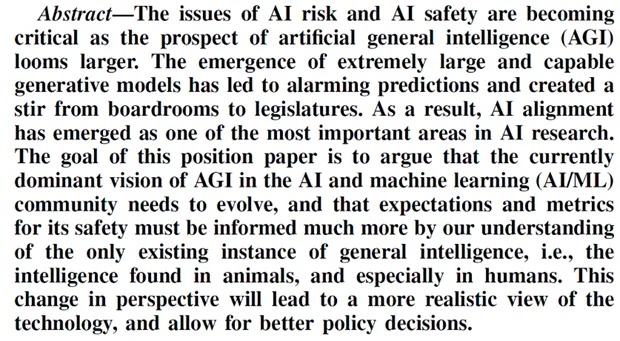

This much we know: Smartphones are making us dumber. Compelling essays suggest we  The main point made in the paper is that, to be meaningful, general intelligence should refer to the kind of intelligence seen in biological agents, and AGI should be given a corresponding meaning in artificial ones. Importantly, any general intelligence must have three attributes – autonomy, self-motivation, and continuous learning – that make it inherently uncertain and uncontrollable. As such, it is no more possible to perfectly align an AI agent with human preferences than it is to align the preferences of individual humans with each other. The best that can be achieved is bounded alignment, defined as demonstrating behavior that is almost always acceptable – though not necessarily agreeable – for almost everyone who encounters the AI agent, which is the degree of alignment we expect from human peers, and which is typically developed through consent and socialization rather than coercion. A crucial point is that, while alignment may refer in the abstract to values and objectives, it can only be validated in terms of behavior, which is the only observable.

The main point made in the paper is that, to be meaningful, general intelligence should refer to the kind of intelligence seen in biological agents, and AGI should be given a corresponding meaning in artificial ones. Importantly, any general intelligence must have three attributes – autonomy, self-motivation, and continuous learning – that make it inherently uncertain and uncontrollable. As such, it is no more possible to perfectly align an AI agent with human preferences than it is to align the preferences of individual humans with each other. The best that can be achieved is bounded alignment, defined as demonstrating behavior that is almost always acceptable – though not necessarily agreeable – for almost everyone who encounters the AI agent, which is the degree of alignment we expect from human peers, and which is typically developed through consent and socialization rather than coercion. A crucial point is that, while alignment may refer in the abstract to values and objectives, it can only be validated in terms of behavior, which is the only observable. ON THE SURFACE, Pan is the coming-of-age story of an ordinary teenage boy struggling with severe panic attacks while doing ordinary teenage things (losing his virginity, fretting over his popularity, negotiating rides to strip malls in the wake of his parents’ divorce) in suburban Illinois. On another level, it’s about a teenager who has possibly been possessed by Pan, the ancient Greek god of the wild, and who falls in with a cult of troubled young drug addicts who attempt to exorcise him.

ON THE SURFACE, Pan is the coming-of-age story of an ordinary teenage boy struggling with severe panic attacks while doing ordinary teenage things (losing his virginity, fretting over his popularity, negotiating rides to strip malls in the wake of his parents’ divorce) in suburban Illinois. On another level, it’s about a teenager who has possibly been possessed by Pan, the ancient Greek god of the wild, and who falls in with a cult of troubled young drug addicts who attempt to exorcise him. Among the most pressing problems societies face today are economic inequality and the erosion of democratic norms and institutions. In fact the two problems—inequality and democratic erosion—are linked. In a large cross-national statistical study of risk factors for democratic erosion, we establish that economic inequality is one of the strongest predictors of where and when democracy erodes. Even wealthy and longstanding democracies are vulnerable if they are highly unequal (though national wealth might provide some resiliency). The association between inequality and risk of democratic backsliding is robust, and holds under different measures and structures of both income inequality and wealth inequality. The association is unlikely to be a case of reverse causation. For concerned citizens seeking to understand why so many democracies are eroding and how to stop this process, our study indicates that policies for ameliorating inequality are a promising path forward.

Among the most pressing problems societies face today are economic inequality and the erosion of democratic norms and institutions. In fact the two problems—inequality and democratic erosion—are linked. In a large cross-national statistical study of risk factors for democratic erosion, we establish that economic inequality is one of the strongest predictors of where and when democracy erodes. Even wealthy and longstanding democracies are vulnerable if they are highly unequal (though national wealth might provide some resiliency). The association between inequality and risk of democratic backsliding is robust, and holds under different measures and structures of both income inequality and wealth inequality. The association is unlikely to be a case of reverse causation. For concerned citizens seeking to understand why so many democracies are eroding and how to stop this process, our study indicates that policies for ameliorating inequality are a promising path forward. The fall of Syria’s prisons and its regime prompted a wave of thought regarding the very notion of carceral collapse—no longer an aspiration for the oppressed but an inclement reality—throughout the region and diaspora. Palestinian factions debated the implications for the 1,784 Palestinian detainees who disappeared in Assad’s prisons, their fate unknown. On the other hand, Sudanese activists took to X in solidarity, recalling their own scenes of prison liberation in Khartoum in the aftermath of the 2019 revolution that toppled the long-standing dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir. In the United Kingdom, Egyptian activists gathered to reiterate their demands for the release of the over sixty thousand political prisoners in President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s prisons, including British Egyptian activist and writer Alaa Abdel Fattah. One former detainee recalled the horrors of Sednaya as “no less horrific” than what he witnessed in Egyptian prisons.

The fall of Syria’s prisons and its regime prompted a wave of thought regarding the very notion of carceral collapse—no longer an aspiration for the oppressed but an inclement reality—throughout the region and diaspora. Palestinian factions debated the implications for the 1,784 Palestinian detainees who disappeared in Assad’s prisons, their fate unknown. On the other hand, Sudanese activists took to X in solidarity, recalling their own scenes of prison liberation in Khartoum in the aftermath of the 2019 revolution that toppled the long-standing dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir. In the United Kingdom, Egyptian activists gathered to reiterate their demands for the release of the over sixty thousand political prisoners in President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s prisons, including British Egyptian activist and writer Alaa Abdel Fattah. One former detainee recalled the horrors of Sednaya as “no less horrific” than what he witnessed in Egyptian prisons. Prisons are American tourist attractions, and criminals who become fugitives or inmates our outlaw heroes—Al Capone, Alcatraz, Charles Manson, Sing Sing, Angola, Luigi Mangione, O. J. Simpson, Diddy, né Sean Combs. A collective underdog fetish means that the image of a civilian outwitting, outrunning, or confronting “the man” is enough to negate his trespasses. Maybe achieving the apotheosis of success in the United States requires becoming a convict, being threatened with or facing real incarceration and exile, doing time, paying dues, and making a grand comeback. At that finale you can sell that story to restore your fortunes, dignity, and maverick glory. Combs is the latest public figure to go from celebrated to disgraced to tentatively redeemed in some eyes by a show trial and the masculine compulsion to cheer when men get away with terrorizing women. The rapper Jay Electronica stood outside of the courtroom with his two Great Danes on the day the verdict was delivered, and announced, “I’m just here supporting my brother.” He looked half-ashamed, half-deviant about it, like he was both courting and afraid of backlash. Others call Diddy’s comeuppance a legal lynching, insinuating he’s a survivor of a because-he’s-black character assassination, since other powerful, abusive men have yet to be held accountable. It’s a truly American malfunction, this belief that the once oppressed should have the freedom to become as evil and ruthlessly decadent as their oppressors. This is what is sold to the public as prestige, and imitations of it exist at every stratum. With this in mind, Diddy’s story could be construed as a bootstraps tale—from Harlem to Howard to Hollywood endings. His recent downward spiral might be just another buoy, one that will help him ascend anew.

Prisons are American tourist attractions, and criminals who become fugitives or inmates our outlaw heroes—Al Capone, Alcatraz, Charles Manson, Sing Sing, Angola, Luigi Mangione, O. J. Simpson, Diddy, né Sean Combs. A collective underdog fetish means that the image of a civilian outwitting, outrunning, or confronting “the man” is enough to negate his trespasses. Maybe achieving the apotheosis of success in the United States requires becoming a convict, being threatened with or facing real incarceration and exile, doing time, paying dues, and making a grand comeback. At that finale you can sell that story to restore your fortunes, dignity, and maverick glory. Combs is the latest public figure to go from celebrated to disgraced to tentatively redeemed in some eyes by a show trial and the masculine compulsion to cheer when men get away with terrorizing women. The rapper Jay Electronica stood outside of the courtroom with his two Great Danes on the day the verdict was delivered, and announced, “I’m just here supporting my brother.” He looked half-ashamed, half-deviant about it, like he was both courting and afraid of backlash. Others call Diddy’s comeuppance a legal lynching, insinuating he’s a survivor of a because-he’s-black character assassination, since other powerful, abusive men have yet to be held accountable. It’s a truly American malfunction, this belief that the once oppressed should have the freedom to become as evil and ruthlessly decadent as their oppressors. This is what is sold to the public as prestige, and imitations of it exist at every stratum. With this in mind, Diddy’s story could be construed as a bootstraps tale—from Harlem to Howard to Hollywood endings. His recent downward spiral might be just another buoy, one that will help him ascend anew. P

P Hence the absurdity of the bland assumption among some writers of the younger generation that Baldwin would embrace the modern idea of intersectionality. Despite his ready admission that he was thrice challenged—Black, queer, and disadvantaged (at least initially!)—Baldwin’s core philosophy was the essential unity of humanity, “his rejection of all labels and fixed notions of identity as ‘myths’ or ‘lies,’” as his biographer Magdalena J. Zaborowska has written,

Hence the absurdity of the bland assumption among some writers of the younger generation that Baldwin would embrace the modern idea of intersectionality. Despite his ready admission that he was thrice challenged—Black, queer, and disadvantaged (at least initially!)—Baldwin’s core philosophy was the essential unity of humanity, “his rejection of all labels and fixed notions of identity as ‘myths’ or ‘lies,’” as his biographer Magdalena J. Zaborowska has written,