Andrea Lius in The Scientist:

Some ants within the colony patrol the neighborhood to protect the nest from intruders, while others stay inside to care for the young. Various molecular mechanisms, from hormone and neuropeptide signaling to gene transcription and epigenetics, underlie these behaviors—some of which are highly conserved in evolution.1,2

Some ants within the colony patrol the neighborhood to protect the nest from intruders, while others stay inside to care for the young. Various molecular mechanisms, from hormone and neuropeptide signaling to gene transcription and epigenetics, underlie these behaviors—some of which are highly conserved in evolution.1,2

…Ant colonies typically consist of queen and worker castes. In some species, such as the carpenter and leafcutter ants, the latter is further divided into multiple subcastes, which scientists can tell apart based on the animals’ size and behavior. Berger’s team previously studied subcaste-specific behavior in carpenter ants, where they found that a hormone called JH3 regulates behavior in the two worker subcastes: Major, the large “soldiers”, and Minor, their smaller counterparts that forage food and nurse the young.4 Next, Berger wanted to understand the molecular bases of behavior in a more complex species: the leafcutter ants.

“The leafcutters are the epitome of the most sophisticated ant system,” Berger said.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I, Justin Smith-Ruiu (ב), born 30071972 and uploaded 18102036, hereby submit to the Council my Petition for immediate and permanent shutdown.

I, Justin Smith-Ruiu (ב), born 30071972 and uploaded 18102036, hereby submit to the Council my Petition for immediate and permanent shutdown. This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture.

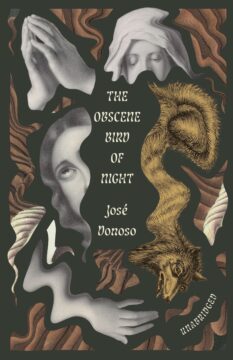

This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture. The Obscene Bird of Night

The Obscene Bird of Night My dear Langston

My dear Langston For starters, ChatGPT said that if billionaires paid taxes like the upper middle class, the government would bring in a lot more money — potentially hundreds of billions of dollars more every year. “That’s because most billionaires don’t make their money from salaries like upper-middle-class workers do. Instead, they grow their wealth through investments–stocks, real estate, and businesses–which are often taxed at much lower rates or not taxed at all until the assets are sold,” ChatGPT told me.

For starters, ChatGPT said that if billionaires paid taxes like the upper middle class, the government would bring in a lot more money — potentially hundreds of billions of dollars more every year. “That’s because most billionaires don’t make their money from salaries like upper-middle-class workers do. Instead, they grow their wealth through investments–stocks, real estate, and businesses–which are often taxed at much lower rates or not taxed at all until the assets are sold,” ChatGPT told me. Designing drugs is a bit like playing with

Designing drugs is a bit like playing with  Every baby is born the same way (namely, as a baby).

Every baby is born the same way (namely, as a baby). Every few years, the tires on your car wear thin and need to be replaced. But where does that lost tire material go?

Every few years, the tires on your car wear thin and need to be replaced. But where does that lost tire material go? Three urgent priorities are set to strain Europe’s public finances over the next few years. The first – and most obvious – is defense. The push to boost military spending is primarily a response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression, compounded by US President Donald Trump’s relentless criticism of America’s NATO allies. Together, these pressures have made strengthening Europe’s defense posture a strategic necessity.

Three urgent priorities are set to strain Europe’s public finances over the next few years. The first – and most obvious – is defense. The push to boost military spending is primarily a response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression, compounded by US President Donald Trump’s relentless criticism of America’s NATO allies. Together, these pressures have made strengthening Europe’s defense posture a strategic necessity.

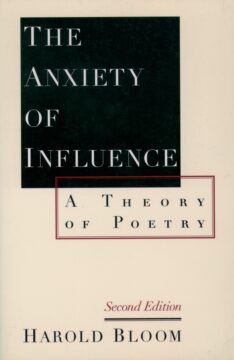

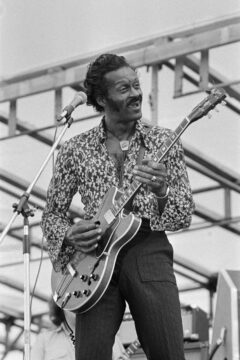

‘There are ten thousand freedoms,’ the late Joshua Clover once said, ‘but rock freedom is definitely set – in the first instance – in a car, when it’s late outside. It can be ecstatic, it can be boring, it can be adjectiveless freedom, but you have reached escape velocity, faster miles an hour, you have no particular place to go, and you have the radio on.’

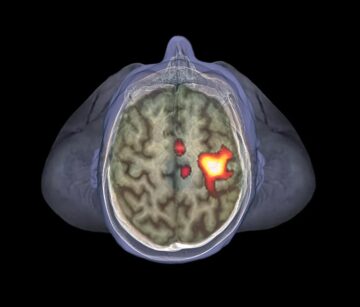

‘There are ten thousand freedoms,’ the late Joshua Clover once said, ‘but rock freedom is definitely set – in the first instance – in a car, when it’s late outside. It can be ecstatic, it can be boring, it can be adjectiveless freedom, but you have reached escape velocity, faster miles an hour, you have no particular place to go, and you have the radio on.’ The brain activates front-line immune cells in response to the mere sight of a sick person, mimicking

The brain activates front-line immune cells in response to the mere sight of a sick person, mimicking