Sophia Pfister in Science:

It was 3 a.m. I was exhausted from taking care of my 3-month-old baby, but I couldn’t sleep. As I tried to recall the topics of the five conference calls on my calendar for the morning, I again had the haunting thought that I wasn’t good enough for my job—a director position I started shortly before my baby was born. I imagined I would make mistakes in my presentations and my team would lose respect for me. Tormented by these thoughts, I reached for a book from the pile on my bedside table to distract myself. By chance I grabbed the Bible, which I had been too busy to read since my baby was born. As I opened it to a random page and happened on the verse “For when I am weak, then I am strong,” tears filled my eyes, and I could breathe again.

It was 3 a.m. I was exhausted from taking care of my 3-month-old baby, but I couldn’t sleep. As I tried to recall the topics of the five conference calls on my calendar for the morning, I again had the haunting thought that I wasn’t good enough for my job—a director position I started shortly before my baby was born. I imagined I would make mistakes in my presentations and my team would lose respect for me. Tormented by these thoughts, I reached for a book from the pile on my bedside table to distract myself. By chance I grabbed the Bible, which I had been too busy to read since my baby was born. As I opened it to a random page and happened on the verse “For when I am weak, then I am strong,” tears filled my eyes, and I could breathe again.

My upbringing gave me an “achiever” personality. From childhood class president to prestigious university degrees to a leadership position in a large company, I was regarded as a “star.” People see me as confident, ambitious, competent, and energetic. But I always feared seeming imperfect in the eyes of others. I worked as hard as I could to make up for my flaws.

But after becoming a new mom and starting a new job, I was unable to excel no matter how hard I worked. The job required me to attend meetings with almost no break between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m., pushing my own work tasks late into the night. I used a breast pump under the table during meetings and frequently forgot to eat. Mental and physical exhaustion from back-to-back meetings and lack of sleep made it difficult to think deeply and creatively about science. I wanted to offer useful comments in meetings, but my thoughts often became muddled, at times leaving me tongue-tied midsentence.

More here.

While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space.

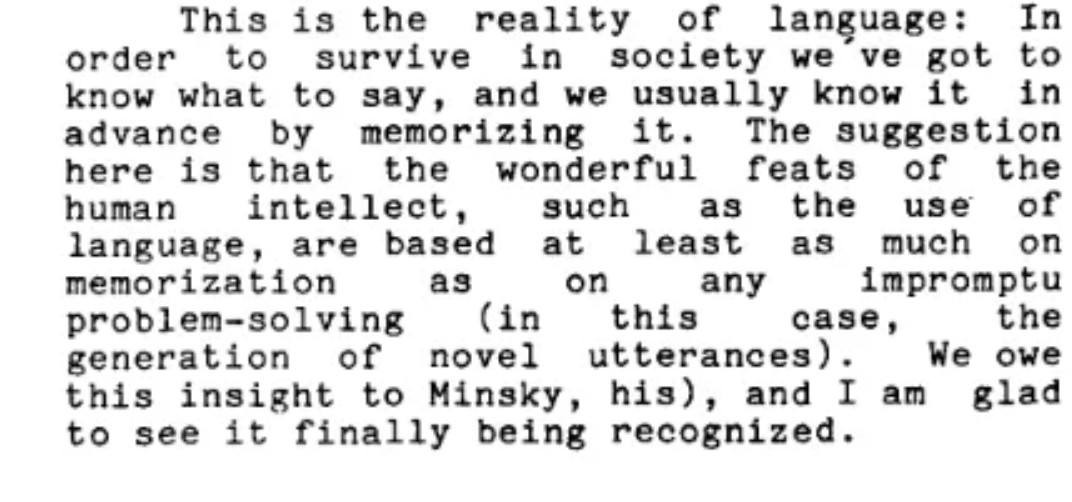

While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space. The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far.

The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far. Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization.

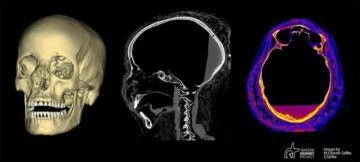

Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization. A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their  In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin

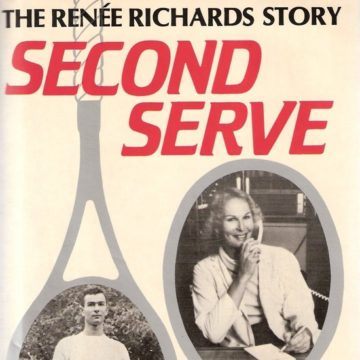

In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin  RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was  We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters.

We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters.