Nora Krug in The Washington Post:

My bookshelves are a mess. It’s not just that I have too many books and too little space. I’m also simply disorganized. It wasn’t always so. Shelves I put together years ago, pre-children, remain generally intact: a full bookcase of poetry, alphabetized by author, and several jam-packed bookcases of fiction, also by authors’ last names. These shelves now serve primarily as decoration or reference or as a lending library for guests. But there’s more, much more: the tumbling pile on my desk — propping up the computer I am typing on — and the volumes stuffed frantically in the bookcase in my bedroom and stacked in towers on and around my nightstand. These are the books that are part of my daily life — for work, for pleasure, sometimes both. There is no rhyme or reason to how I arrange them, but as I read in one of the books I consulted (then discarded) to help deal with my little problem: “If it’s where you meant it to be, then it’s organized.” I am adopting that as my book-organizing principle. Don’t tell my kids.

My bookshelves are a mess. It’s not just that I have too many books and too little space. I’m also simply disorganized. It wasn’t always so. Shelves I put together years ago, pre-children, remain generally intact: a full bookcase of poetry, alphabetized by author, and several jam-packed bookcases of fiction, also by authors’ last names. These shelves now serve primarily as decoration or reference or as a lending library for guests. But there’s more, much more: the tumbling pile on my desk — propping up the computer I am typing on — and the volumes stuffed frantically in the bookcase in my bedroom and stacked in towers on and around my nightstand. These are the books that are part of my daily life — for work, for pleasure, sometimes both. There is no rhyme or reason to how I arrange them, but as I read in one of the books I consulted (then discarded) to help deal with my little problem: “If it’s where you meant it to be, then it’s organized.” I am adopting that as my book-organizing principle. Don’t tell my kids.

More here.

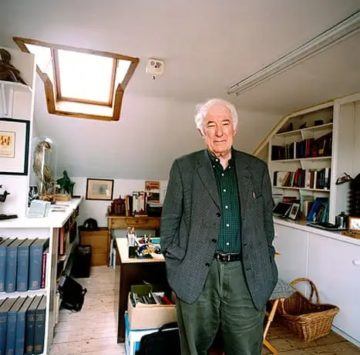

In the summer of 2012 Seamus Heaney wrote to me on some questions I had sent him about dictionaries and words and etymologies. Bits of what he had to say made it into a couple of talks I did around that time, but I recently rediscovered the original text, and thought it should see the light of day. So here’s a very lightly edited rendition of our exchange:

In the summer of 2012 Seamus Heaney wrote to me on some questions I had sent him about dictionaries and words and etymologies. Bits of what he had to say made it into a couple of talks I did around that time, but I recently rediscovered the original text, and thought it should see the light of day. So here’s a very lightly edited rendition of our exchange:

In a recent

In a recent  Pretexts:

Pretexts: Researchers in the Biomedical Engineering Department at UConn have developed a new cardiac cell-derived platform that closely mimics the human heart, unlocking potential for more thorough preclinical drug development and testing, and model for cardiac diseases. The research, published in Cell Reports by Assistant Professor Kshitiz in collaboration with Dr. Junaid Afzal in the cardiology department at the University of California San Francisco, presents a method that accelerates maturation of human cardiac cells towards a state suitable enough to be a surrogate for preclinical drug testing.

Researchers in the Biomedical Engineering Department at UConn have developed a new cardiac cell-derived platform that closely mimics the human heart, unlocking potential for more thorough preclinical drug development and testing, and model for cardiac diseases. The research, published in Cell Reports by Assistant Professor Kshitiz in collaboration with Dr. Junaid Afzal in the cardiology department at the University of California San Francisco, presents a method that accelerates maturation of human cardiac cells towards a state suitable enough to be a surrogate for preclinical drug testing. Around you, there is piracy and chaos. But you’re enterprising, and keep to your path. At university, you hardly sleep, and you eat what you can afford. Why do you work yourself this way? It’s not as if you’re getting paid for it. Another version of yourself, in another time, though, is. Now, living in the California sun with some success, you reflect on your poor, wan, sleepless younger self and feel a wave of gratitude, and then of prickly regret. The kid you were had different dreams; it strikes you as unfair that you sit pretty on the spoils of that person’s efforts. If you could take some of your wealth and send it backward in time, to your younger self, you would.

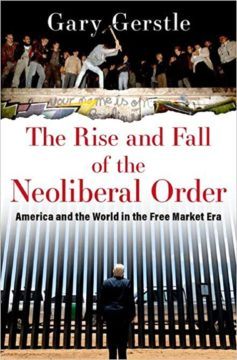

Around you, there is piracy and chaos. But you’re enterprising, and keep to your path. At university, you hardly sleep, and you eat what you can afford. Why do you work yourself this way? It’s not as if you’re getting paid for it. Another version of yourself, in another time, though, is. Now, living in the California sun with some success, you reflect on your poor, wan, sleepless younger self and feel a wave of gratitude, and then of prickly regret. The kid you were had different dreams; it strikes you as unfair that you sit pretty on the spoils of that person’s efforts. If you could take some of your wealth and send it backward in time, to your younger self, you would. Intellectual histories of recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “

Intellectual histories of recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “ In 1868, the mathematician Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) proclaimed that an encryption scheme called the Vigenère cipher was “unbreakable.” He had no proof, but he had compelling reasons for his belief, since mathematicians had been trying unsuccessfully to break the cipher for more than three centuries.

In 1868, the mathematician Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) proclaimed that an encryption scheme called the Vigenère cipher was “unbreakable.” He had no proof, but he had compelling reasons for his belief, since mathematicians had been trying unsuccessfully to break the cipher for more than three centuries. The scientist James Lovelock’s discoveries had an immense influence on our understanding of the global impact of humankind, and on the search for extraterrestrial life. A vigorous writer and speaker, he became a hero to the green movement, although he was one of its most formidable critics.

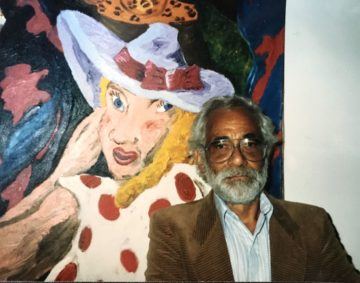

The scientist James Lovelock’s discoveries had an immense influence on our understanding of the global impact of humankind, and on the search for extraterrestrial life. A vigorous writer and speaker, he became a hero to the green movement, although he was one of its most formidable critics. “Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott,” a clamorous retrospective at the New Museum, bodes to be enjoyed by practically everyone who sees it, though some may be nagged by inklings that they shouldn’t. For more than three decades, until he was slowed by health ailments in the two-thousands—he died in 2009, at the age of eighty-three—the impetuous figurative painter danced across minefields of racial and sexual provocation, celebrating libertine romance and cannibalizing canonical art history by way of appreciative parody. He was born in California, the son of musicians from New Orleans. His mother, certainly, and possibly his father, who worked as a railroad waiter, had enslaved ancestors, but both of them—and Colescott—could pass for white. As Matthew Weseley, the co-curator of the show with Lowery Stokes Sims, recounts in the splendid catalogue, Colescott’s mother insisted on the ruse, which he adopted. The mild-mannered modernism of his early works, sampled at the New Museum, affords no hints to the contrary.

“Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott,” a clamorous retrospective at the New Museum, bodes to be enjoyed by practically everyone who sees it, though some may be nagged by inklings that they shouldn’t. For more than three decades, until he was slowed by health ailments in the two-thousands—he died in 2009, at the age of eighty-three—the impetuous figurative painter danced across minefields of racial and sexual provocation, celebrating libertine romance and cannibalizing canonical art history by way of appreciative parody. He was born in California, the son of musicians from New Orleans. His mother, certainly, and possibly his father, who worked as a railroad waiter, had enslaved ancestors, but both of them—and Colescott—could pass for white. As Matthew Weseley, the co-curator of the show with Lowery Stokes Sims, recounts in the splendid catalogue, Colescott’s mother insisted on the ruse, which he adopted. The mild-mannered modernism of his early works, sampled at the New Museum, affords no hints to the contrary.