Noam Maggor in the European Review of Books:

Saint Domingue was the crown jewel of the French empire in the Caribbean when its slaves rebelled in 1791. They formed the independent republic of Haiti in 1804, but the terms of the island’s separation from France was contested long thereafter, and French reconquest loomed. In 1825, in order to secure their sovereignty, the Haitians were forced (in the words of Charles X’s decree) « to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity » for the human property that had been lost. The total sum of these reparations was 150 million golden francs, which the new Caribbean nation funded through a massive loan, paid back slowly over decades. Generations of Haitians – deep into the twentieth century – contributed a significant portion of their livelihood to support the descendants of those who had kidnapped their ancestors from Africa in the hundreds of thousands and forced them to labor under genocidal conditions.

Saint Domingue was the crown jewel of the French empire in the Caribbean when its slaves rebelled in 1791. They formed the independent republic of Haiti in 1804, but the terms of the island’s separation from France was contested long thereafter, and French reconquest loomed. In 1825, in order to secure their sovereignty, the Haitians were forced (in the words of Charles X’s decree) « to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity » for the human property that had been lost. The total sum of these reparations was 150 million golden francs, which the new Caribbean nation funded through a massive loan, paid back slowly over decades. Generations of Haitians – deep into the twentieth century – contributed a significant portion of their livelihood to support the descendants of those who had kidnapped their ancestors from Africa in the hundreds of thousands and forced them to labor under genocidal conditions.

The French aristocrat and intellectual Alexis De Tocqueville is best remembered for his prophetic insights into American democracy, but in 1843 he turned his attention to Haiti. When the indemnity arrangement was again debated in France, Tocqueville declared his unqualified support for the deal, calling it « fair to all participating parties. » Not only would it compensate slaveholders for their lost property, he argued, and restore the social order that had been badly undermined by the rebellion.

More here.

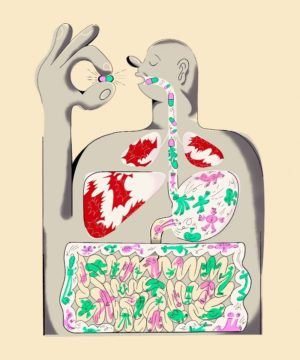

Almost as soon as it was floated in 1965 by Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Schildkraut, the serotonin hypothesis of

Almost as soon as it was floated in 1965 by Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Schildkraut, the serotonin hypothesis of  Term limits or other

Term limits or other

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters

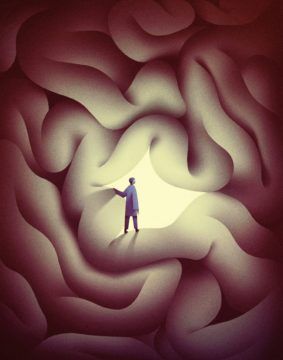

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters  It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories.

It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories. CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK—

CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK— For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong.

For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong. Germans call it

Germans call it  Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”:

Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”: I

I In Arabia Through the Looking Glass, when he wasn’t comparing everything to Alice in Wonderland, Jonathan Raban likened his experiences in the Gulf States at the height of the 1970s oil boom to passing through a ‘time loop’ into Britain at the heyday of the Industrial Revolution. Today – in polite academic circles, at least – it would constitute a major faux pas to compare the societies of the Middle East with those at some earlier stage of Western historical development. Yet, forty years on, one gains a strikingly similar impression from John McManus’s picture of life in 21st-century Qatar, from the outsized ambition, the extraordinary rate of economic growth and the transformation of the urban environment to the dreadful working conditions, the open racial hierarchies and the persistence of traditional rentier elites. To venture ‘inside Qatar’ in 2022, as McManus puts it, is to get a ‘glimpse of life at the coalface of globalisation’.

In Arabia Through the Looking Glass, when he wasn’t comparing everything to Alice in Wonderland, Jonathan Raban likened his experiences in the Gulf States at the height of the 1970s oil boom to passing through a ‘time loop’ into Britain at the heyday of the Industrial Revolution. Today – in polite academic circles, at least – it would constitute a major faux pas to compare the societies of the Middle East with those at some earlier stage of Western historical development. Yet, forty years on, one gains a strikingly similar impression from John McManus’s picture of life in 21st-century Qatar, from the outsized ambition, the extraordinary rate of economic growth and the transformation of the urban environment to the dreadful working conditions, the open racial hierarchies and the persistence of traditional rentier elites. To venture ‘inside Qatar’ in 2022, as McManus puts it, is to get a ‘glimpse of life at the coalface of globalisation’. Flora Bigelow Dodge had not traveled to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in January 1903 for the same reason so many women of her acquaintance had. She did not do anything for the same reason other women did—at least not if you believed the newspapers. A fixture in the society pages, Flora was the “most daring, most original, cleverest woman in New York.” She was a wonderful musician, a graceful dancer, an expert horsewoman, and a captivating storyteller, an author of plays and short stories. She was “both courageous and imaginative.” She was witty, ambitious, generous, and beautiful, a woman of “unusual individuality” with a retinue of admirers.

Flora Bigelow Dodge had not traveled to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in January 1903 for the same reason so many women of her acquaintance had. She did not do anything for the same reason other women did—at least not if you believed the newspapers. A fixture in the society pages, Flora was the “most daring, most original, cleverest woman in New York.” She was a wonderful musician, a graceful dancer, an expert horsewoman, and a captivating storyteller, an author of plays and short stories. She was “both courageous and imaginative.” She was witty, ambitious, generous, and beautiful, a woman of “unusual individuality” with a retinue of admirers. Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them.

Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them.