Alisson Wilkinson in Vox:

Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.”

Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.”

In fact, numerous studies seem to suggest that when it comes to the psychological benefits of reading, just doing it might matter as much or more than the content. Researchers have found that people who spend a few hours per week reading books live longer than those who don’t read, or who read only articles in periodicals; the sustained act of cognition that books demand seems to be the deciding factor. Other research finds a vast array of social-cognitive benefits that come with reading, particularly reading fiction, aiding the brain’s development in understanding others and imagining the world.

Some studies have suggested that reading fiction can increase empathy. But a perhaps even more surprising finding comes from researchers who discovered a short-term decrease in the need for “cognitive closure” in the minds of readers of fiction. In brief, the researchers write, those with a high need for cognitive closure “need to reach a quick conclusion in decision-making and an aversion to ambiguity and confusion,” and thus, when confronted with confusing circumstances, tend to seize on fast explanations and hang on to them. That generally means they’re more susceptible to things like conspiracy theories and poor information, and they become less rational in their thinking. Reading fiction, though, studies have found, tends to retrain the brain to stay open, comfortable with ambiguity, and able to sort through information more carefully.

More here.

We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already becoming normal in southern Europe, and would be counted among the cooler days during hot periods in parts of the Middle East, Africa and South Asia, where heat is becoming a regular threat to life. It cannot now be long, unless immediate and comprehensive measures are taken, before these days of rage become the norm even in our once-temperate climatic zone.

We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already becoming normal in southern Europe, and would be counted among the cooler days during hot periods in parts of the Middle East, Africa and South Asia, where heat is becoming a regular threat to life. It cannot now be long, unless immediate and comprehensive measures are taken, before these days of rage become the norm even in our once-temperate climatic zone.

Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them.

Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them. In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.”

In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.” CLAES OLDENBURG IS THE SINGLE Pop artist to have added significantly to the history of form. In order to perceive this, however, one must look beyond the Rabelaisian absurdity of his grotesque imagery to the inventiveness of his shapes, techniques, and materials. These are sufficiently original to identify Oldenburg, not, as he has erroneously been seen, as a chef d’ecole of Pop art, but as one of the most vital innovators in the field of contemporary sculpture, whose vision has affected the work of many other young artists of his generation.

CLAES OLDENBURG IS THE SINGLE Pop artist to have added significantly to the history of form. In order to perceive this, however, one must look beyond the Rabelaisian absurdity of his grotesque imagery to the inventiveness of his shapes, techniques, and materials. These are sufficiently original to identify Oldenburg, not, as he has erroneously been seen, as a chef d’ecole of Pop art, but as one of the most vital innovators in the field of contemporary sculpture, whose vision has affected the work of many other young artists of his generation. After 20 years spent recovering long-lost artifacts and priceless art from across the globe, Dutch art detective Arthur Brand thought his career had peaked. He wondered how any case could top those that turned up a stolen Picasso or the pair of bronze horses made for Adolf Hitler once believed to have been destroyed by the Soviet army.

After 20 years spent recovering long-lost artifacts and priceless art from across the globe, Dutch art detective Arthur Brand thought his career had peaked. He wondered how any case could top those that turned up a stolen Picasso or the pair of bronze horses made for Adolf Hitler once believed to have been destroyed by the Soviet army.

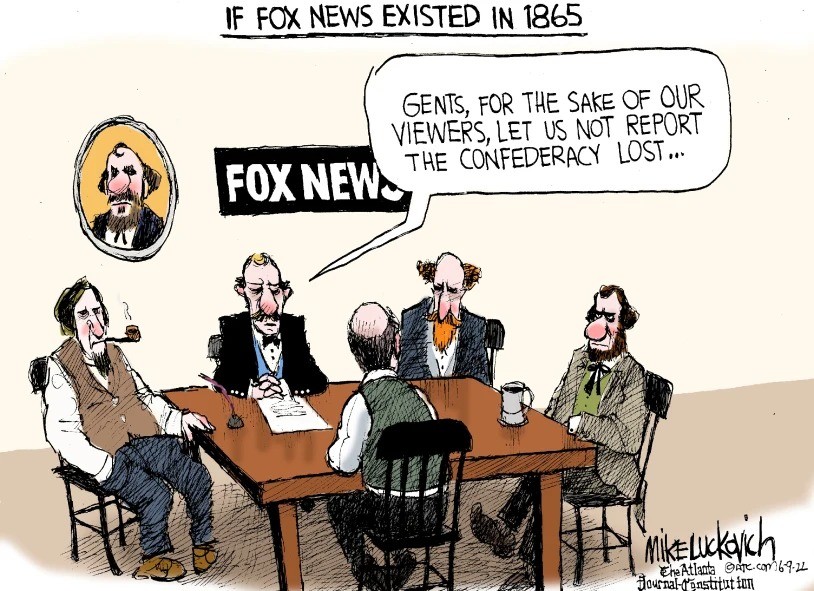

Many of the things that you believe right now—in this very moment—are utterly wrong.

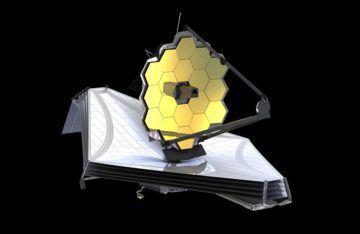

Many of the things that you believe right now—in this very moment—are utterly wrong. Scientists are reporting that damage sustained to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) during a micrometeoroid strike in late May 2022 may be worse than first thought.

Scientists are reporting that damage sustained to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) during a micrometeoroid strike in late May 2022 may be worse than first thought. Ms. Koo wondered whether people who started out at the bottom and achieved high status would support public policies to assist other strivers like themselves. Or, having successfully climbed the socioeconomic ladder, would they perceive upward social mobility as less difficult? “If I did it, why can’t they do it?” Ms. Koo asked rhetorically.

Ms. Koo wondered whether people who started out at the bottom and achieved high status would support public policies to assist other strivers like themselves. Or, having successfully climbed the socioeconomic ladder, would they perceive upward social mobility as less difficult? “If I did it, why can’t they do it?” Ms. Koo asked rhetorically. Sylvia Plath is the Diane Arbus of poetry, the verbal equivalent of her visual art. Since Arbus and Plath had strikingly similar lives, it’s surprising that they never mentioned each other and that their biographers have not compared them. They were self-destructive sexual adventurers, angry and rebellious, driven and ambitious. Both suffered extreme depression, had nervous breakdowns and committed suicide. But they used their mania to deepen their awareness and inspire their art, and created photographs and poetry to impose order on their chaotic lives. They shared an ability to combine the ordinary with the grotesque and monstrous, and expressed anguished feelings with macabre humor. Arbus was consciously and deliberately bohemian, Plath outwardly conventional yet inwardly raging. Both explored the dark side of human existence and revealed their own torments.

Sylvia Plath is the Diane Arbus of poetry, the verbal equivalent of her visual art. Since Arbus and Plath had strikingly similar lives, it’s surprising that they never mentioned each other and that their biographers have not compared them. They were self-destructive sexual adventurers, angry and rebellious, driven and ambitious. Both suffered extreme depression, had nervous breakdowns and committed suicide. But they used their mania to deepen their awareness and inspire their art, and created photographs and poetry to impose order on their chaotic lives. They shared an ability to combine the ordinary with the grotesque and monstrous, and expressed anguished feelings with macabre humor. Arbus was consciously and deliberately bohemian, Plath outwardly conventional yet inwardly raging. Both explored the dark side of human existence and revealed their own torments. Katia and Maurice Krafft were both born in the 1940s in the Rhine valley, close to the Miocene Kaiser volcano, though they didn’t know each other as children. They met on a park bench when they were students at the University of Strasbourg, and from that moment on, according to their joint obituary in the Bulletin of Volcanology, ‘volcanic eruptions became the common passion to which everything else in their life seemed subordinate’. They married in 1970, formed a crack team of volcano-chasers, équipe volcanique, and set off to get as close as they possibly could to the very edge of every fiery crater, to collect samples and data and just to be there, ecstatic with the enormity of it all, like a pair of mad moths drawn into a candle flame.

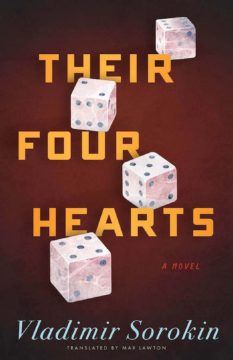

Katia and Maurice Krafft were both born in the 1940s in the Rhine valley, close to the Miocene Kaiser volcano, though they didn’t know each other as children. They met on a park bench when they were students at the University of Strasbourg, and from that moment on, according to their joint obituary in the Bulletin of Volcanology, ‘volcanic eruptions became the common passion to which everything else in their life seemed subordinate’. They married in 1970, formed a crack team of volcano-chasers, équipe volcanique, and set off to get as close as they possibly could to the very edge of every fiery crater, to collect samples and data and just to be there, ecstatic with the enormity of it all, like a pair of mad moths drawn into a candle flame. ALTHOUGH VLADIMIR SOROKIN has earned his reputation as Russia’s premier satirist, he deserves more credit for being among its finest metaphysicians. In Russia, as the saying goes, fiction is philosophy. Though very few Russian philosophers have established a position for themselves in the Western canon, the particularities of Russian thought still find their way into the global imagination through the work of literary greats like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Sorokin, known as much for his stylistic range as for his prescient depictions of Russia’s shifting sociopolitical tides, is a standard-bearer in this venerable tradition.

ALTHOUGH VLADIMIR SOROKIN has earned his reputation as Russia’s premier satirist, he deserves more credit for being among its finest metaphysicians. In Russia, as the saying goes, fiction is philosophy. Though very few Russian philosophers have established a position for themselves in the Western canon, the particularities of Russian thought still find their way into the global imagination through the work of literary greats like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Sorokin, known as much for his stylistic range as for his prescient depictions of Russia’s shifting sociopolitical tides, is a standard-bearer in this venerable tradition. It was the first in

It was the first in Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.”

Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.”