Zain and Swetz in Scientific American:

Sūnya, nulla, ṣifr, zevero, zip and zilch are among the many names of the mathematical concept of nothingness. Historians, journalists and others have variously identified the symbol’s birthplace as the Andes mountains of South America, the flood plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the surface of a calculating board in the Tang dynasty of China, a cast iron column and temple inscriptions in India, and most recently, a stone epigraphic inscription found in Cambodia.

Sūnya, nulla, ṣifr, zevero, zip and zilch are among the many names of the mathematical concept of nothingness. Historians, journalists and others have variously identified the symbol’s birthplace as the Andes mountains of South America, the flood plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the surface of a calculating board in the Tang dynasty of China, a cast iron column and temple inscriptions in India, and most recently, a stone epigraphic inscription found in Cambodia.

The tracing of zero’s heritage has been elusive. For a country to be able to claim the number’s origin would provide a sense of ownership and determine a source of great nationalistic pride.

Throughout the 20th century, this ownership rested in India. That’s where an inscription was discovered, holding the number “0” in reference to land measurement inside a temple in the central Indian city of Gwalior. In 1883 the renowned German Indologist and philologist, Eugen Julius Theodor Hultzsch copied and translated the inscription into English, dating the text to the year C.E. 876. And this has been accepted as the oldest known date for the appearance of zero. However, a series of stones in what is now Sumatra, casts India’s ownership of nothingness in doubt, and several investigators agree that the first reference of zero was likely on a set of stones found on the island.

More here.

The Green New Deal is so dead that uttering the name now sounds like a bitter joke. Other ambitious plans like Jay Inslee’s were ignored. Biden’s more realistic plan was killed by Joe Manchin. Polls like the one that Wallace-Wells cite above

The Green New Deal is so dead that uttering the name now sounds like a bitter joke. Other ambitious plans like Jay Inslee’s were ignored. Biden’s more realistic plan was killed by Joe Manchin. Polls like the one that Wallace-Wells cite above  While I defend the existence and utility of IQ and its principal component, general intelligence or g, in the study of individual differences, I think it’s completely irrelevant to AI, AI scaling, and AI safety. It’s a measure of differences among humans within the restricted range they occupy, developed more than a century ago. It’s a statistical construct with no theoretical foundation, and it has tenuous connections to any mechanistic understanding of cognition other than as an omnibus measure of processing efficiency (speed of neural transmission, amount of neural tissue, and so on). It exists as a coherent variable only because performance scores on subtests like vocabulary, digit string memorization, and factual knowledge intercorrelate, yielding a statistical principal component, probably a global measure of neural fitness.

While I defend the existence and utility of IQ and its principal component, general intelligence or g, in the study of individual differences, I think it’s completely irrelevant to AI, AI scaling, and AI safety. It’s a measure of differences among humans within the restricted range they occupy, developed more than a century ago. It’s a statistical construct with no theoretical foundation, and it has tenuous connections to any mechanistic understanding of cognition other than as an omnibus measure of processing efficiency (speed of neural transmission, amount of neural tissue, and so on). It exists as a coherent variable only because performance scores on subtests like vocabulary, digit string memorization, and factual knowledge intercorrelate, yielding a statistical principal component, probably a global measure of neural fitness. American Stutter, 2019–2021, novelist Steve Erickson’s journal of our ongoing plague year — the everything-at-once-all-the-time mash-up of election, pandemic, and still-unresolved attempted coup — springs from a clarifying rage that not only scorns right-wing perfidy but also looks askance at liberal good intentions (and their too-often ether-brained descendants, progressive good intentions). In Erickson’s view, liberal humanism is just not up to the job of preventing America from becoming a democracy in name only. His voice in this book is simultaneously that of a soldier exhorting his fellow combatants to get off their asses and rush with him into enemy fire, and of a disillusioned man wiping the dirt off his hands as he walks away from the grave of American democracy. It is hopeful and fierce and already grieving.

American Stutter, 2019–2021, novelist Steve Erickson’s journal of our ongoing plague year — the everything-at-once-all-the-time mash-up of election, pandemic, and still-unresolved attempted coup — springs from a clarifying rage that not only scorns right-wing perfidy but also looks askance at liberal good intentions (and their too-often ether-brained descendants, progressive good intentions). In Erickson’s view, liberal humanism is just not up to the job of preventing America from becoming a democracy in name only. His voice in this book is simultaneously that of a soldier exhorting his fellow combatants to get off their asses and rush with him into enemy fire, and of a disillusioned man wiping the dirt off his hands as he walks away from the grave of American democracy. It is hopeful and fierce and already grieving. There’s something odd about the sky in Giuseppe Cesari’s rendition of Perseus and Andromeda. The blue is too bright, too saturated; it has a hyperreal quality that feels appropriate for a myth. This luminous sky and its fuzzy wisps of cloud were not picked out by an artist’s brush, but rather, formed by geological forces. The painting is worked on a chunk of polished lapis lazuli. It’s a visual pun: in the myth, Andromeda was chained to a rock, just as her image is secured to a stone in this painting. Cesari returned to this story over and over, producing versions on wood panels, on limestone, and on slate. Each substrate contributes to the painting in its own way:

There’s something odd about the sky in Giuseppe Cesari’s rendition of Perseus and Andromeda. The blue is too bright, too saturated; it has a hyperreal quality that feels appropriate for a myth. This luminous sky and its fuzzy wisps of cloud were not picked out by an artist’s brush, but rather, formed by geological forces. The painting is worked on a chunk of polished lapis lazuli. It’s a visual pun: in the myth, Andromeda was chained to a rock, just as her image is secured to a stone in this painting. Cesari returned to this story over and over, producing versions on wood panels, on limestone, and on slate. Each substrate contributes to the painting in its own way:  “I am for Kool-art, 7-Up art, Pepsi-art, Sunshine art, 39 cents art, 15 cents art. . . . I am for an art of things lost or thrown away on the way home from school.” When the artist Claes Oldenburg, who authored these words in 1961, died this week at ninety-three, one had a sense that it had been a long while since his vision, for good or ill, had engaged the center ring of the art world’s attention. If he had not exactly disappeared from view, he had faded a little. Examples of his outsized, monumental tributes to the sheer thingness of ordinary things, celebrated in the Whitman-esque list above, could be found in many American cities—a giant clothespin in Philadelphia, shuttlecocks in Kansas City—but, though his sculptures are often beloved, they exist by now more as local color than as visionary art. They have become, in an irony that Oldenburg would have appreciated, numbered among the vernacular eccentricities that have always dotted the American landscape: the giant elephant in Margate, the duck on Long Island, or the giant pickle that once stood at Fifth Avenue and Broadway.

“I am for Kool-art, 7-Up art, Pepsi-art, Sunshine art, 39 cents art, 15 cents art. . . . I am for an art of things lost or thrown away on the way home from school.” When the artist Claes Oldenburg, who authored these words in 1961, died this week at ninety-three, one had a sense that it had been a long while since his vision, for good or ill, had engaged the center ring of the art world’s attention. If he had not exactly disappeared from view, he had faded a little. Examples of his outsized, monumental tributes to the sheer thingness of ordinary things, celebrated in the Whitman-esque list above, could be found in many American cities—a giant clothespin in Philadelphia, shuttlecocks in Kansas City—but, though his sculptures are often beloved, they exist by now more as local color than as visionary art. They have become, in an irony that Oldenburg would have appreciated, numbered among the vernacular eccentricities that have always dotted the American landscape: the giant elephant in Margate, the duck on Long Island, or the giant pickle that once stood at Fifth Avenue and Broadway. Caring less doesn’t mean negligence. To care less about inconsequential matters, you need to zero in on what is worth caring for. Consider taking stock of to-do list items and obligations and asking if these responsibilities make your day feel more spacious or more confined, Cohan suggests. Does it nourish your sense of creativity? Is it the best use of your time and talent? Does it make you feel exhausted? Do you want to spend your time and energy on this?

Caring less doesn’t mean negligence. To care less about inconsequential matters, you need to zero in on what is worth caring for. Consider taking stock of to-do list items and obligations and asking if these responsibilities make your day feel more spacious or more confined, Cohan suggests. Does it nourish your sense of creativity? Is it the best use of your time and talent? Does it make you feel exhausted? Do you want to spend your time and energy on this? One evening in his Paris flat, Édouard Louis, the French literary star who shot to fame at 21 with

One evening in his Paris flat, Édouard Louis, the French literary star who shot to fame at 21 with  On an early autumn day in 1992, E Bruce Harrison, a man widely acknowledged as the father of environmental PR, stood up in a room full of business leaders and delivered a pitch like no other.

On an early autumn day in 1992, E Bruce Harrison, a man widely acknowledged as the father of environmental PR, stood up in a room full of business leaders and delivered a pitch like no other. Many people have strong opinions about abortion – especially in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, revoking a constitutional right previously held by more than 165 million Americans.

Many people have strong opinions about abortion – especially in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, revoking a constitutional right previously held by more than 165 million Americans. NATO traditionally maintains strong deterrence and defense, while it has also led the way toward detente and dialogue. NATO’s current commitment to deterrence and defense is clear. But to restart conversations, NATO must now also find a way to encourage détente and dialogue.

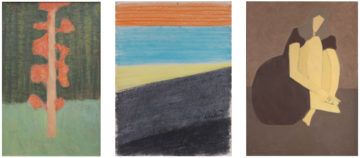

NATO traditionally maintains strong deterrence and defense, while it has also led the way toward detente and dialogue. NATO’s current commitment to deterrence and defense is clear. But to restart conversations, NATO must now also find a way to encourage détente and dialogue. Even the critic Clement Greenberg, who had earlier dismissed Avery, came to acknowledge the unique liminal quality of his work, which hovers between representational and non-representational art. “There is the sublime lightness of Avery’s hand on the one side,” he noted, “and the morality of the eye on the other: the exact loyalty of these eyes to what they experience.” A negotiation between Avery’s instinct for “sublime lightness” and the optical exactitude of what his eyes actually experienced can be heard echoing from every canvas. Avery’s art, Greenberg poetically observed, “floats, but it also coheres and stays in place, as tight as a drum and as open as light”.

Even the critic Clement Greenberg, who had earlier dismissed Avery, came to acknowledge the unique liminal quality of his work, which hovers between representational and non-representational art. “There is the sublime lightness of Avery’s hand on the one side,” he noted, “and the morality of the eye on the other: the exact loyalty of these eyes to what they experience.” A negotiation between Avery’s instinct for “sublime lightness” and the optical exactitude of what his eyes actually experienced can be heard echoing from every canvas. Avery’s art, Greenberg poetically observed, “floats, but it also coheres and stays in place, as tight as a drum and as open as light”. WHEN STEVE BARNHILL moved into his dead uncle’s old room, he decided it was time to finally read the man’s mysterious book. It was the mid-1970s, in his aunt’s house in Huntington, a small West Virginia city on the border of Ohio and Kentucky. He recalls the book sitting on a shelf, a slim hardcover volume dressed in taupe cloth and stamped with bold red letters: Waiting for Nothing.

WHEN STEVE BARNHILL moved into his dead uncle’s old room, he decided it was time to finally read the man’s mysterious book. It was the mid-1970s, in his aunt’s house in Huntington, a small West Virginia city on the border of Ohio and Kentucky. He recalls the book sitting on a shelf, a slim hardcover volume dressed in taupe cloth and stamped with bold red letters: Waiting for Nothing. L

L Truth is democracy’s most important moral value. We work out our direction, as a society, through public discourse. Power and wealth confer an advantage in this: the more people you can reach (by virtue of enjoying easy access to the media, or even controlling sections of it), the more likely you are to bring others round to your point of view. The rich and powerful may be able to reach more people but, if their arguments are required to conform to reality, we can at least hold them to account. Truth is a great leveller.

Truth is democracy’s most important moral value. We work out our direction, as a society, through public discourse. Power and wealth confer an advantage in this: the more people you can reach (by virtue of enjoying easy access to the media, or even controlling sections of it), the more likely you are to bring others round to your point of view. The rich and powerful may be able to reach more people but, if their arguments are required to conform to reality, we can at least hold them to account. Truth is a great leveller.