Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Thomas Oatley:

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s response have fractured global order. Western governments will not be able to piece the system back together. The invasion, as well as the broader foreign policy that produced it, indicate that Putin’s Russia is unwilling to continue as a subordinate member of a Western-led international order.

Debate over the West’s supposed responsibility for triggering the invasion has focused narrowly on the developing relationship between Ukraine and NATO and the extent to which this threatens Russian security. This focus has led analysts to neglect the broader question of how Putin views Russia’s place in the contemporary world order, as well as the extent to which the invasion constitutes an attempt to change this system.

Yet these broader concerns appear to play an important role in the regime’s calculations. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has commented that Russia’s invasion

is “rooted in the U.S. and West’s desire to rule the world,” and reflects a determination by Russia to create “a multipolar, just, democratic world order.”

Regardless of the outcome in Ukraine, therefore, Russia’s dissatisfaction with its subordinate status in the Liberal Order (does one peer tell another that it stands on the “wrong side of history”?) and determination to restructure it will persist. Consequently, Russia will not reintegrate into this order.

More here.

Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs.

Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs.

With its recent

With its recent  Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020.

Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020. Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher

Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher  t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that

t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that  If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly  Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson):

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson): The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of

The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of  The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives.

The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives. Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the

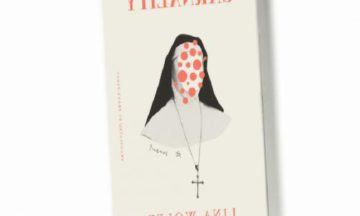

Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the  “Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

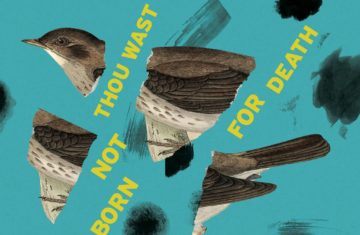

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life. Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”