Richard Hughes Gibson at The Hedgehog Review:

What is a paragraph? Consult a writing guide, and you will receive an answer like this: “A paragraph is a group of sentences that develops one central idea.” However solid such a definition appears on the page, it quickly melts in the heat of live instruction, as any writing teacher will tell you. Faced with the task of assembling their own paragraphs, students find nearly every word in the formula problematic. How many sentences belong in the “group?” Somewhere along the way, many were taught that five or six will do. But then out there in the world, they have seen (or heard rumors of) bulkier and slimmer specimens, some spilling over pages, some consisting of a single sentence. And how does one go about “developing” a central idea? Is there a magic number of subpoints or citations? Most problematic of all is the notion of the main “idea” itself. What qualifies? Facts? Propositions? Your ideas? Someone else’s?

What is a paragraph? Consult a writing guide, and you will receive an answer like this: “A paragraph is a group of sentences that develops one central idea.” However solid such a definition appears on the page, it quickly melts in the heat of live instruction, as any writing teacher will tell you. Faced with the task of assembling their own paragraphs, students find nearly every word in the formula problematic. How many sentences belong in the “group?” Somewhere along the way, many were taught that five or six will do. But then out there in the world, they have seen (or heard rumors of) bulkier and slimmer specimens, some spilling over pages, some consisting of a single sentence. And how does one go about “developing” a central idea? Is there a magic number of subpoints or citations? Most problematic of all is the notion of the main “idea” itself. What qualifies? Facts? Propositions? Your ideas? Someone else’s?

more here.

AT THE BEGINNING OF

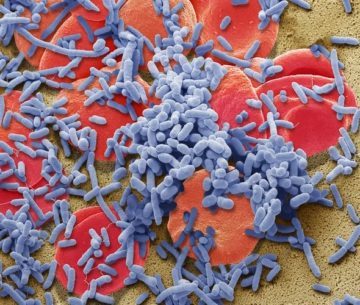

AT THE BEGINNING OF Hospital patients are at risk of a number of life-threatening complications, especially sepsis—a condition that can kill within hours and contributes to one out of three

Hospital patients are at risk of a number of life-threatening complications, especially sepsis—a condition that can kill within hours and contributes to one out of three  Shortly after my parents died in 2017, I nearly lost custody of my dog, Zoe, in my divorce. When we were reunited, I remember telling her firmly, “You cannot die now,” even though she had just turned 15. Not long after, the vet told me that new lab work indicated kidney failure. I was quite glad then that Zoe couldn’t talk, at least not in the traditional sense. We had no painful discussions about quality-of-life issues or end-of-life concerns.

Shortly after my parents died in 2017, I nearly lost custody of my dog, Zoe, in my divorce. When we were reunited, I remember telling her firmly, “You cannot die now,” even though she had just turned 15. Not long after, the vet told me that new lab work indicated kidney failure. I was quite glad then that Zoe couldn’t talk, at least not in the traditional sense. We had no painful discussions about quality-of-life issues or end-of-life concerns. In 2017, I published my fourth novel,

In 2017, I published my fourth novel,  The omicron variant did indeed become

The omicron variant did indeed become  On the fourth page of Pure Colour, the fourth and most recent novel by the Canadian writer Sheila Heti, it is proposed that there are three kinds of beings on the face of the earth. They are each a different kind of “critic,” tasked with helping God to improve upon His “first draft” of the universe. There are birds who “consider the world as if from a distance” and are interested in beauty above all. There are fish who “critique from the middle” and are consumed by the “condition of the many.” And there are bears who “do not have a pragmatic way of thinking” and are “deeply consumed with their own.” The three main characters in the novel track with the three types: Mira, the art critic and main character, is a bird; Mira’s father, whose death takes up the middle part of the novel, is a bear; and Mira’s romantic interest and colleague at a school for art critics, Annie, is a fish.

On the fourth page of Pure Colour, the fourth and most recent novel by the Canadian writer Sheila Heti, it is proposed that there are three kinds of beings on the face of the earth. They are each a different kind of “critic,” tasked with helping God to improve upon His “first draft” of the universe. There are birds who “consider the world as if from a distance” and are interested in beauty above all. There are fish who “critique from the middle” and are consumed by the “condition of the many.” And there are bears who “do not have a pragmatic way of thinking” and are “deeply consumed with their own.” The three main characters in the novel track with the three types: Mira, the art critic and main character, is a bird; Mira’s father, whose death takes up the middle part of the novel, is a bear; and Mira’s romantic interest and colleague at a school for art critics, Annie, is a fish. Americans aged sixty-two and older are the fastest-growing demographic of student borrowers. Of the forty-five million Americans who hold student debt, one in five are over fifty years old. Between 2004 and 2018, student-loan balances for borrowers over fifty increased by five hundred and twelve per cent. Perhaps because policymakers have considered student debt as the burden of upwardly mobile young people, inaction has seemed a reasonable response, as if time itself will solve the problem. But, in an era of declining wages and rising debt, Americans are not aging out of their student loans—they are aging into them.

Americans aged sixty-two and older are the fastest-growing demographic of student borrowers. Of the forty-five million Americans who hold student debt, one in five are over fifty years old. Between 2004 and 2018, student-loan balances for borrowers over fifty increased by five hundred and twelve per cent. Perhaps because policymakers have considered student debt as the burden of upwardly mobile young people, inaction has seemed a reasonable response, as if time itself will solve the problem. But, in an era of declining wages and rising debt, Americans are not aging out of their student loans—they are aging into them. Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another. I was bothered by the hashtag campaign. Not by the male response, which ranged from outraged and cynical to condescending, nor the way the media dove in because the campaign was useful fodder. I recoiled from the gendering of pain, the installation of victimhood into the definition of femininity—and from the way pain became a polemic.

Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another. I was bothered by the hashtag campaign. Not by the male response, which ranged from outraged and cynical to condescending, nor the way the media dove in because the campaign was useful fodder. I recoiled from the gendering of pain, the installation of victimhood into the definition of femininity—and from the way pain became a polemic. W

W Gregory Afinogenov in The Nation (illustration by Lily Qian):

Gregory Afinogenov in The Nation (illustration by Lily Qian): Patrick Iber interviews Matt Duss in Dissent:

Patrick Iber interviews Matt Duss in Dissent: N

N