Modern Fiction

First book assigned in Modern Fiction

is Joseph Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus.

The professor: dandelion lady

tall & thin, an old head capped

in gray-blonde wisps, spits

the hard R from her chest day one,

then again day two, then switches

to the Conrad novel every other time

like she’s not sure if there’s a max

before graves beneath her feet—below floor

and stair and brick—snap,

reach high, and drag down.

Tour guides say Thomas Jefferson went here,

but none detail the dense

death that shrouds

Williamsburg grounds,

the dead who live well

and those who stay dead.

Thomas Jefferson is a modern fiction.

The students here call him TJ,

his statue fixed to Old Campus like a sundial

telling no time but these, Read more »

The most striking thing about this remarkable surface was how easy it was to ignore. It flooded the entire floor surface so perfectly that it just seemed natural that you would glide on this cornucopia of shapes and textures, which made no attempt to reference the space of the hotel or the urban context around it. There was something else. Spending enough time observing the space made it clear that the carpet works in support of the hotel’s organization, in setting an atmosphere, and in moving people in inexplicable ways. “Why does it look like that?” was therefore followed by “What does it do?” during that long afternoon of carpet watching. As it turned out, there were no simple answers. The historians were not alone in their ignorance: front desk clerks and hotel managers, perfectly capable of guiding you through the thickets of the city’s urban history or recommending the right drink at the bar, had no idea who designed the carpet and with what motives.

The most striking thing about this remarkable surface was how easy it was to ignore. It flooded the entire floor surface so perfectly that it just seemed natural that you would glide on this cornucopia of shapes and textures, which made no attempt to reference the space of the hotel or the urban context around it. There was something else. Spending enough time observing the space made it clear that the carpet works in support of the hotel’s organization, in setting an atmosphere, and in moving people in inexplicable ways. “Why does it look like that?” was therefore followed by “What does it do?” during that long afternoon of carpet watching. As it turned out, there were no simple answers. The historians were not alone in their ignorance: front desk clerks and hotel managers, perfectly capable of guiding you through the thickets of the city’s urban history or recommending the right drink at the bar, had no idea who designed the carpet and with what motives. Criticism in the broadest sense is a key tactic for maintaining a nonrigid, noncomplacent orientation toward the world. You’re always stepping back and looking at everything afresh, never taking anything for granted, never turning a blind eye to your own complicities and flaws—ideally, anyway. We are committed to criticism not as a way of formulating value judgments but as a literary-artistic-intellectual practice that has a relationship to irony as defined by Friedrich Schlegel: “clear consciousness of an eternal agility.” It’s also related to Adorno’s comment that “it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.” The common denominator that links irony with Adorno’s remark is this: Never get too comfortable, never be quite congruent with yourself, and never assume anything else is entirely congruent with itself.

Criticism in the broadest sense is a key tactic for maintaining a nonrigid, noncomplacent orientation toward the world. You’re always stepping back and looking at everything afresh, never taking anything for granted, never turning a blind eye to your own complicities and flaws—ideally, anyway. We are committed to criticism not as a way of formulating value judgments but as a literary-artistic-intellectual practice that has a relationship to irony as defined by Friedrich Schlegel: “clear consciousness of an eternal agility.” It’s also related to Adorno’s comment that “it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.” The common denominator that links irony with Adorno’s remark is this: Never get too comfortable, never be quite congruent with yourself, and never assume anything else is entirely congruent with itself. Despite his many intellectual achievements, I suspect there are some concepts my dog cannot conceive of, or even contemplate. He can sit on command and fetch a ball, but I suspect that he cannot imagine that the metal can containing his food is made from processed rocks. I suspect he cannot imagine that the slowly lengthening white lines in the sky are produced by machines also made from rocks like his cans of dog food. I suspect he cannot imagine that these flying repurposed dog food cans in the sky look so small only because they are so high up. And I wonder: is there any way that my dog could know that these ideas even exist? It doesn’t take long for this question to spread elsewhere. Soon I start to wonder about concepts that I don’t know exist: concepts whose existence I can never even suspect, let alone contemplate. What can I ever know about that which lies beyond the limits of what I can even imagine?

Despite his many intellectual achievements, I suspect there are some concepts my dog cannot conceive of, or even contemplate. He can sit on command and fetch a ball, but I suspect that he cannot imagine that the metal can containing his food is made from processed rocks. I suspect he cannot imagine that the slowly lengthening white lines in the sky are produced by machines also made from rocks like his cans of dog food. I suspect he cannot imagine that these flying repurposed dog food cans in the sky look so small only because they are so high up. And I wonder: is there any way that my dog could know that these ideas even exist? It doesn’t take long for this question to spread elsewhere. Soon I start to wonder about concepts that I don’t know exist: concepts whose existence I can never even suspect, let alone contemplate. What can I ever know about that which lies beyond the limits of what I can even imagine? People throughout history have imagined ideal societies of various sorts. As the twentieth century dawned, advances in manufacturing and communication arguably brought the idea of utopia within our practical reach, at least as far as economic necessities are concerned. But we failed to achieve it, to say the least. Brad DeLong’s new book,

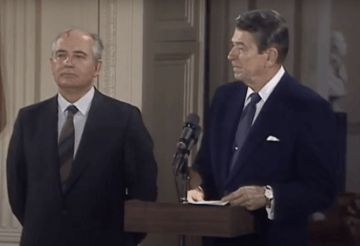

People throughout history have imagined ideal societies of various sorts. As the twentieth century dawned, advances in manufacturing and communication arguably brought the idea of utopia within our practical reach, at least as far as economic necessities are concerned. But we failed to achieve it, to say the least. Brad DeLong’s new book,  Mikhail Gorbachev presented a figure of Greek tragedy proportions. Possessing good intentions and intellectual curiosity, Gorbachev nonetheless became the most reviled man in Russia, following the USSR’s demise. Yet, with Gorbachev, his worst qualities were connected to his best. Gorbachev was the wrong man at the wrong time to resolve the contradictions created by the Stalinist and then Brezhnev bureaucratic model of really-existing socialism in the Soviet Union. Increasingly hated at home, Gorbachev was beloved by world leaders in the “West” as the man who peacefully (at least by the comparative metrics of collapsing empires) unwound the USSR, even if trying to save its all-union character. Meanwhile, for China, Gorbachev delivered lessons in what not to do when reforming a sclerotic post-Stalinist system requiring economic reforms, if not transformation.

Mikhail Gorbachev presented a figure of Greek tragedy proportions. Possessing good intentions and intellectual curiosity, Gorbachev nonetheless became the most reviled man in Russia, following the USSR’s demise. Yet, with Gorbachev, his worst qualities were connected to his best. Gorbachev was the wrong man at the wrong time to resolve the contradictions created by the Stalinist and then Brezhnev bureaucratic model of really-existing socialism in the Soviet Union. Increasingly hated at home, Gorbachev was beloved by world leaders in the “West” as the man who peacefully (at least by the comparative metrics of collapsing empires) unwound the USSR, even if trying to save its all-union character. Meanwhile, for China, Gorbachev delivered lessons in what not to do when reforming a sclerotic post-Stalinist system requiring economic reforms, if not transformation. In 2016, Hillary Clinton

In 2016, Hillary Clinton  By 2050, nearly 7 out of 10 people in the world will live in cities, up from just over half in 2020. Urbanization is nothing new, but an effort is under way across many high-income countries to make their cities smarter, using data, instrumentation and more efficient resource management. In most of these nations, the vast majority of smart-city projects involve upgrades to existing infrastructure. Japan stands out for its willingness to build smart communities from scratch as it grapples with a rapidly ageing population and a shrinking workforce, meaning that there are fewer people of working age to support older people.

By 2050, nearly 7 out of 10 people in the world will live in cities, up from just over half in 2020. Urbanization is nothing new, but an effort is under way across many high-income countries to make their cities smarter, using data, instrumentation and more efficient resource management. In most of these nations, the vast majority of smart-city projects involve upgrades to existing infrastructure. Japan stands out for its willingness to build smart communities from scratch as it grapples with a rapidly ageing population and a shrinking workforce, meaning that there are fewer people of working age to support older people. Imagine someone told you that politics is a “great game,” that when citizens respect just principles, they do so “in much the same way that players have the shared end to execute a good and fair play of the game.” You would probably wonder if they meant it, if they really believed that civic duties resemble those acquired when “we join a game, namely, the obligations to play by the rules and to be a good sport.” You would because, for most people, politics is a serious business.

Imagine someone told you that politics is a “great game,” that when citizens respect just principles, they do so “in much the same way that players have the shared end to execute a good and fair play of the game.” You would probably wonder if they meant it, if they really believed that civic duties resemble those acquired when “we join a game, namely, the obligations to play by the rules and to be a good sport.” You would because, for most people, politics is a serious business. Isaac Newton was not known for his generosity of spirit, and his disdain for his rivals was legendary. But in one letter to his competitor Gottfried Leibniz, now known as the Epistola Posterior, Newton comes off as nostalgic and almost friendly. In it, he tells a story from his student days, when he was just beginning to learn mathematics. He recounts how he made a major discovery equating areas under curves with infinite sums by a process of guessing and checking. His reasoning in the letter is so charming and accessible, it reminds me of the pattern-guessing games little kids like to play.

Isaac Newton was not known for his generosity of spirit, and his disdain for his rivals was legendary. But in one letter to his competitor Gottfried Leibniz, now known as the Epistola Posterior, Newton comes off as nostalgic and almost friendly. In it, he tells a story from his student days, when he was just beginning to learn mathematics. He recounts how he made a major discovery equating areas under curves with infinite sums by a process of guessing and checking. His reasoning in the letter is so charming and accessible, it reminds me of the pattern-guessing games little kids like to play. AP: So, it’s not just the presence of English loanwords, but also how much of the original German novel is about who speaks in English and how that is a marker [of identity]. Nivedita grew up in Germany; her cousin Priti grew up in England. They meet because Priti comes to Germany to study the language for several summers in their youth. In the original, you see her command of German develop: she speaks a lot of English at first, and then, as the novel progresses, she’s speaking more and more German. Nivedita comments, “Wow, you know, Priti’s German was really getting good.” Basically, Priti is marked as the most “English” or British—the most not German character starting out. This couldn’t be replicated exactly in English, so I had to look for other little ways to solve it (like Priti mixing German into her speech in the English translation). That was one of the tricky things, and I never know how successfully I’ve solved a challenge. Beyond the character of Priti, I wanted to find ways to make it clear that Identitti originates in another language and then was brought into English. Some novels are inherently built that way because they’re constantly mentioning places or names. There are markers such that the reader never forgets that it’s happening where it’s happening. I didn’t want the North American reader to forget that the story they’re reading is taking place in Dusseldorf, Germany. But I also didn’t want to weigh the translation down with these unnecessary reminders. It was a fine line to walk.

AP: So, it’s not just the presence of English loanwords, but also how much of the original German novel is about who speaks in English and how that is a marker [of identity]. Nivedita grew up in Germany; her cousin Priti grew up in England. They meet because Priti comes to Germany to study the language for several summers in their youth. In the original, you see her command of German develop: she speaks a lot of English at first, and then, as the novel progresses, she’s speaking more and more German. Nivedita comments, “Wow, you know, Priti’s German was really getting good.” Basically, Priti is marked as the most “English” or British—the most not German character starting out. This couldn’t be replicated exactly in English, so I had to look for other little ways to solve it (like Priti mixing German into her speech in the English translation). That was one of the tricky things, and I never know how successfully I’ve solved a challenge. Beyond the character of Priti, I wanted to find ways to make it clear that Identitti originates in another language and then was brought into English. Some novels are inherently built that way because they’re constantly mentioning places or names. There are markers such that the reader never forgets that it’s happening where it’s happening. I didn’t want the North American reader to forget that the story they’re reading is taking place in Dusseldorf, Germany. But I also didn’t want to weigh the translation down with these unnecessary reminders. It was a fine line to walk. I

I