Dylan Matthews in Vox:

So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

But to DeLong, who beyond his academic work is known for his widely read blog on economics, something incredible happened in that sliver of time that eluded our species for the other 99.95 percent of our history. Whereas before 1870, technological progress proceeded slowly, if at all, after 1870 it accelerated dramatically. And especially for residents of rich countries, this technological progress brought a world of unprecedented plenty.

More here.

James Gallagher in BBC:

Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus was able to survive for up to 72 hours on some surfaces, but that is nothing compared to sturdier species. Norovirus – known as the winter vomiting bug – can survive outside the body for two weeks while waiting for somebody new to infect. The team of chemists and virologists investigated self-sterilising materials that reduce the risk of contaminated surfaces spreading infections.

Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus was able to survive for up to 72 hours on some surfaces, but that is nothing compared to sturdier species. Norovirus – known as the winter vomiting bug – can survive outside the body for two weeks while waiting for somebody new to infect. The team of chemists and virologists investigated self-sterilising materials that reduce the risk of contaminated surfaces spreading infections.

Jeff Tollefson in Nature:

In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and curtailed climate regulations. Although the decisions differed in rationale, they share a distinct trait: all three dismissed substantial evidence about how the court’s rulings would affect public health and safety. It is a troubling trend that many scientists fear could undermine the role of scientific evidence in shaping public policy. Now, as the court prepares to consider a landmark case on electoral policies, many worry about the future of American democracy itself.

In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and curtailed climate regulations. Although the decisions differed in rationale, they share a distinct trait: all three dismissed substantial evidence about how the court’s rulings would affect public health and safety. It is a troubling trend that many scientists fear could undermine the role of scientific evidence in shaping public policy. Now, as the court prepares to consider a landmark case on electoral policies, many worry about the future of American democracy itself.

Often regarded as the most powerful court in the free world, the Supreme Court sits in judgment of laws enacted by Congress and state legislatures, as well as constitutional disputes at any level of government. Its unusual power, in comparison to high courts in other democracies, derives in part from its small size and the fact that its nine justices are appointed for life, says Nancy Gertner, a retired federal judge who teaches at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This makes appointments both highly consequential and highly political. Partisan divisions in the US government make passing new laws difficult and adopting constitutional amendments next to impossible, meaning that the court’s word on crucial issues — such as the right to an abortion — can stand as the law of the land for a generation or more.

More here.

Tuesday, September 13, 2022

Ed Simon at Poetry Magazine:

In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not Ben Jonson, who is so clearly of the Renaissance, or sublime George Herbert, enmeshed in the theology of his day. Not Thomas Traherne, whose beautiful mysticism demands a high price of entry, or Andrew Marvell, a chameleon whose politics are now so distant. Even Shakespeare, with all those Ren-Faire jester hats and jigs, is more a subject of that far country of the past than is Donne. An uncertain Catholic and then a recalcitrant Protestant, Donne was a skeptic, an agnostic who knew that in doubt comes faith. His is a “quintessence even from nothingness, / From dull privations, and lean emptiness […] I am re-begot / Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.” If his age saw the first glimmerings of such anxieties, then Donne reads as modern before modernity because his manuscripts circulated among courtiers and poets. Yet only God can generate from a vacuum, and Rundell explains that Donne’s family and their faith “would haunt him for life. … To read him is to know that we cannot ever expect to shake off our family: only to pick up the skull, the tooth, and walk on.”

In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not Ben Jonson, who is so clearly of the Renaissance, or sublime George Herbert, enmeshed in the theology of his day. Not Thomas Traherne, whose beautiful mysticism demands a high price of entry, or Andrew Marvell, a chameleon whose politics are now so distant. Even Shakespeare, with all those Ren-Faire jester hats and jigs, is more a subject of that far country of the past than is Donne. An uncertain Catholic and then a recalcitrant Protestant, Donne was a skeptic, an agnostic who knew that in doubt comes faith. His is a “quintessence even from nothingness, / From dull privations, and lean emptiness […] I am re-begot / Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.” If his age saw the first glimmerings of such anxieties, then Donne reads as modern before modernity because his manuscripts circulated among courtiers and poets. Yet only God can generate from a vacuum, and Rundell explains that Donne’s family and their faith “would haunt him for life. … To read him is to know that we cannot ever expect to shake off our family: only to pick up the skull, the tooth, and walk on.”

more here.

Peter Orner at The Paris Review:

So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound.

So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound.

His last sip of champagne. The whole thing about the popping of the cork, I forget what exactly. The enigmatic words he likely never said: Has the sailor left? But wouldn’t it be wonderful if he had said them? What sailor? Where’d he go?

His wife, the actress Olga Knipper, wrote that a huge black moth careened around the room crashing into light bulbs as he took his final breaths. Olga was present in the room, of course, but I don’t think she was above creating myths, either. They had only so little time together, less than five years.

more here.

Lynne Segal in the Boston Review:

Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive.

Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive.

More here.

Kevin Hartnett in Quanta:

If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated.

If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated.

This distinction is at the heart of Claude Shannon’s theory of information. Introduced in an epochal 1948 paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” it provides a rigorous mathematical framework for quantifying the amount of information needed to accurately send and receive a message, as determined by the degree of uncertainty around what the intended message could be saying.

Which is to say, it’s time for an example.

More here.

Hippolyte Fofack in Project Syndicate:

Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence.

Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence.

Developing countries’ GDP growth has exceeded the global average over the past several years, and their economies are projected to expand by 3.6% on average in 2022, compared to world growth of 3.2%, according to the International Monetary Fund. But the income and welfare gaps between them and the advanced economies have widened, especially where GDP has consistently expanded at the expense of total wealth and future prosperity.

This counterintuitive development reflects a combination of factors.

More here.

Drone: The Pilot’s Wife in Church

She wears a kind of doily hair-pinned to her crown,

her glory, the pastor says. She stands and the hymn

is sung along with the keyboard, the electric

guitar and the lead singer, heavy eyeliner, a tear

in the voice. The pastor stands at the rail, waiting

on sinners, scanning the congregation.

What should she pray? That her husband’s hands

should stop shaking? That he should stop working

on the Sabbath? That he should stop having those dreams,

stop getting up and playing video games in the dark?

Stop turning out the lights and then talking?

Stop not talking? Stop hating her for listening?

Stop killing those men who kill us? Stop killing

those children who cluster around them? Stop

the women who he must watch collect the bodies,

parts of bodies, who are themselves sometimes nothing

but bodies? Stop watching the bodies get into carts,

into trucks, into the trunks of cars? Stop being paid

for watching, for locating, for prosecuting,

for firing? Stop fighting for the insurance to pay,

for the VA to pay, for the government to pay.

What should she pray? How can God answer?

by Kim Garcia

from The Brooklyn Quarterly

Nancy Walecki in Harveard Magazine:

IS A GAS GUZZLER actually better for the environment than an electric vehicle? Sometimes. Ashley Nunes, Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program fellow, and undergraduate economics concentrator Lucas Woodley ’23 found that many electric vehicle (EV) owners—usually wealthy individuals incentivized by federal tax credits to purchase an electric vehicle as a second car—are doing more environmental harm than good. Why? They’re not driving enough.

IS A GAS GUZZLER actually better for the environment than an electric vehicle? Sometimes. Ashley Nunes, Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program fellow, and undergraduate economics concentrator Lucas Woodley ’23 found that many electric vehicle (EV) owners—usually wealthy individuals incentivized by federal tax credits to purchase an electric vehicle as a second car—are doing more environmental harm than good. Why? They’re not driving enough.

To build an electric-car battery, manufacturers need lithium, and to find lithium, they need the high-altitude salt flats of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. There, beneath turquoise brine lakes, is mud rich in manganese, potassium, borax, and lithium salts. It’s chemical- and water-intensive to isolate lithium from all that mud, and it takes even more energy to make a functional car battery from it. As a result, building a clean-burning EV battery is twice as greenhouse-gas-intensive as making a conventional internal combustion engine.

More here.

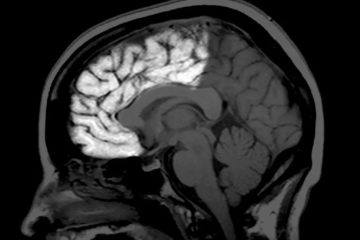

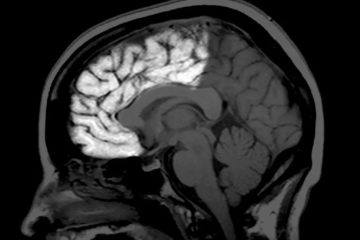

Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new study published in Science on Thursday.

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new study published in Science on Thursday.

“What we found is one gene that certainly contributes to making us human,” said Wieland Huttner, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, and one of the authors of the study. The human brain allows us to do things that other living species cannot, such as using full-blown language and making complicated plans for the future. For decades, scientists have been comparing the anatomy of our brain to that of other mammals to understand how those sophisticated faculties evolved.

Monday, September 12, 2022

by Andrew Bard Schmookler

Evil: Lost and Found

Evil: Lost and Found

Over the centuries, for people whose worldview was governed by the religions of Western civilization, it was reasonably straightforward to conceive of the existence of a “Force of Evil.” Judeo-Christian religion personified such a force in the figure of Satan, or the Devil.

The image of this Supernatural Being enabled people to form some intuitive conception of a powerful force that makes bad things happen: the Devil, with malevolent intent, was always working to get people to do what they shouldn’t do, and to degrade the human world generally.

Wielding his powers with diabolical cleverness, the Devil could make the world uglier. (Quoth Luther: “For still our ancient foe / Doth seek to work us woe;/ His craft and power are great/ And, armed with cruel hate./ On earth is not his equal.”)

The more recent historical emergence of a secular worldview has meant that — in the minds of a major component of the Western world — this supernatural figure has disappeared from people’s picture of what’s real in our world, with nothing equivalent to take its place. And this disappearance of Satan left most of those people with no way of conceiving the possibility of anything existing that might reasonably be called a “Force of Evil.” Read more »

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Sean Trott in Psyche:

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost 18 million words from published texts, the word can occurs about 70,000 times, while souse occurs only once. But can doesn’t just occur more frequently – it’s also much more ambiguous. That is, it has many possible meanings. Can sometimes refers to a container for storing food or drink (‘He drinks beer straight from the can’), but it also doubles as a verb about the process of putting things in a container (‘I need to can this food’), and as a modal verb about one’s ability or permission to do something (‘She can open the can’). It even occasionally moonlights as a verb about getting fired (‘Can they can him for stealing that can?’), and as an informal noun for prison (‘Well, it’s better than a year in the can’).

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost 18 million words from published texts, the word can occurs about 70,000 times, while souse occurs only once. But can doesn’t just occur more frequently – it’s also much more ambiguous. That is, it has many possible meanings. Can sometimes refers to a container for storing food or drink (‘He drinks beer straight from the can’), but it also doubles as a verb about the process of putting things in a container (‘I need to can this food’), and as a modal verb about one’s ability or permission to do something (‘She can open the can’). It even occasionally moonlights as a verb about getting fired (‘Can they can him for stealing that can?’), and as an informal noun for prison (‘Well, it’s better than a year in the can’).

This multiplicity of possible uses raises a question: how do can, souse and other words each end up with the particular numbers of meanings they have? The answer could rest in fundamental, competing forces that shape the evolution of languages.

More here.

Sara Reardon in Nature:

More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science1,2, dramatically increased the number of brain cells in the hominins that preceded modern humans, probably giving them a cognitive advantage over their Neanderthal cousins.

More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science1,2, dramatically increased the number of brain cells in the hominins that preceded modern humans, probably giving them a cognitive advantage over their Neanderthal cousins.

“This is a surprisingly important gene,” says Arnold Kriegstein, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. However, he expects that it will turn out to be one of many genetic tweaks that gave humans an evolutionary advantage over other hominins. “I think it sheds a whole new light on human evolution.”

When researchers first fully sequenced a Neanderthal genome in 20143, they identified 96 amino acids — the building blocks that make up proteins — that differ between Neanderthals and modern humans in addition to a number of other genetic tweaks. Scientists have been studying this list to learn which of these helped modern humans to outcompete Neanderthals and other hominins.

More here.

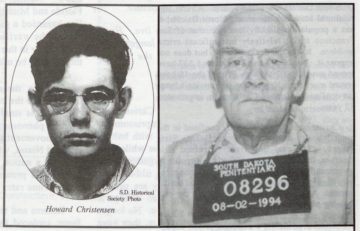

Jessica Pishko in JSTOR Daily:

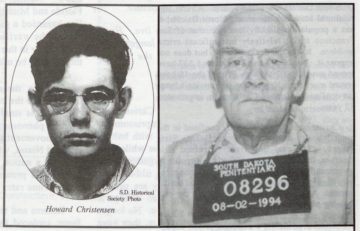

In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “The Living Dead.” They did not mince words describing men like Christensen, who was 74 at the time of the story: “[They are] grey and withered by decades of imprisonment. Faded men who plod prison yards with halting steps, nursing a spark of ersatz hope while they wait to die.”

In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “The Living Dead.” They did not mince words describing men like Christensen, who was 74 at the time of the story: “[They are] grey and withered by decades of imprisonment. Faded men who plod prison yards with halting steps, nursing a spark of ersatz hope while they wait to die.”

In a special issue on “The Living Dead,” the publication details the stories of people who had served an unthinkable number of decades behind bars and astutely points out that the number of people serving sentences of two decades or more was only growing. That prediction proved painfully accurate, as Hope Reese writes in, “What Should We Do about Our Aging Prison Population?”

In 1994, the problem of prison sentences that constituted life or de facto life (50 years or more) felt dire to theI writers of The Angolite article. They counted 2,099 “long-timers” compared to the then 775,624 total number of incarcerated people, or 0.3%. But those statistics pale in comparison to today’s. Now, that number is over 200,000 out of the 1.4 million total people in prison.

More here.

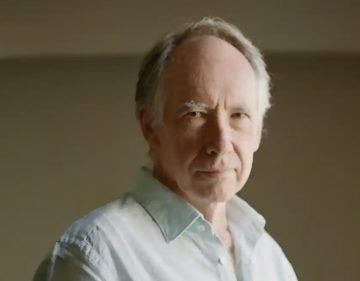

Lisa Allardice in The Guardian:

Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of Midnight’s Children, which transformed both British and Indian writing, and won the Booker prize that year. “It was amazing, it expanded horizons,” McEwan says. “Salman is a great conversationalist, with a great taste for fun and mischief,” he adds. “So we all got on straight away.”

Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of Midnight’s Children, which transformed both British and Indian writing, and won the Booker prize that year. “It was amazing, it expanded horizons,” McEwan says. “Salman is a great conversationalist, with a great taste for fun and mischief,” he adds. “So we all got on straight away.”

McEwan’s ambition with Lessons, his 18th novel, was to show the ways in which “global events penetrate individual lives”, of which the fatwa was a perfect example. “It was a world-historical moment that had immediate personal effects, because we had to learn to think again, to learn the language of free speech,” he says. “It was a very steep learning curve.”

More here.

So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus

Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus  In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and

In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and  In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not

In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not  So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound.

So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound. Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive.

Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive. If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated.

If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated. Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence.

Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence. IS A GAS GUZZLER

IS A GAS GUZZLER Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new  Evil: Lost and Found

Evil: Lost and Found Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost  More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science

More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “

In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “ Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of

Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of