Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):

Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):

Darya Dugina, a twenty-nine-year-old Russian television commentator, was laid to rest at an undisclosed location in Moscow on August 23rd. Three days earlier, Dugina had attended a festival called Tradition, a daylong event that, this year, included a lecture by her father, the self-styled political philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, on the metaphysical dualism of historical thinking. The gathering concluded with a concert called “The Russian Cosmos.” Afterward, Darya Dugina drove away in a Toyota Land Cruiser. The car exploded, killing her. Aleksandr Dugin was apparently travelling in a different vehicle, and it seems likely that whoever killed Darya had meant to kill her better-known father. There has since been much speculation about the identity and motives of the killers, but little is known for certain. Still, some theories are better than others.

Western media accounts have portrayed Dugin as a sort of Putin whisperer, the brains behind the Kremlin’s ideology. He is not that, but his story tells a lot about recent Russian history and the current state of Russian society. Dugin came out of the Moscow cultural underground. The son of minor members of the Soviet nomenklatura, he was expelled from college and educated himself by reading banned and restricted literature. When I was researching Dugin’s story for my book “The Future Is History,” an ex-partner of his and the mother of his older child, Evgeniya Debryanskaya, remembered that Dugin, then in his early twenties, procured a copy of Martin Heidegger’s “Being and Time” on microfilm. He did not, of course, have a microfilm reader at home, so he rigged up a device designed for showing simple children’s reels and projected the book onto his desk. The arrangement was not ideal: it showed a barely visible mirror image of the text. Dugin read Heidegger backward, in the dark, and, according to Debryanskaya, lost some of his eyesight in the process. The symbolic potential of this story is staggering. Its literal meaning is informative: Dugin’s ability to self-educate was limited by censorship, isolation, and ignorance.

Much of Pakistan is now underwater.

Much of Pakistan is now underwater.

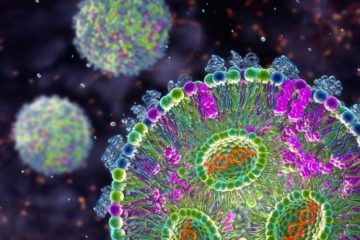

Can messenger RNA (mRNA) train the immune system to attack cancers that resist conventional treatments? To find out, researchers at Atlantic Health System are conducting

Can messenger RNA (mRNA) train the immune system to attack cancers that resist conventional treatments? To find out, researchers at Atlantic Health System are conducting  There are some artists, scientists, and economists whose oeuvre is significant for philosophers even though we generally overlook them. This occurs because too often we deem worthy of philosophical interpretation only other philosophers and their investigations. But there are figures who have provided philosophers with new cultural, scientific, and political paradigms who are absent from our philosophical traditions. Although we could say they were philosophers without defining themselves as such, their works have often presented innovative concepts, meanings, and truths that give them the same ontological status as the work of other philosophers. For most continental thinkers—as analytic philosophers still believe our discipline is circumscribed exclusively to logical problems derived from mathematics and science—these figures are vital to understanding our past, present, and also future.

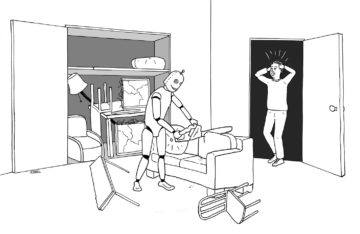

There are some artists, scientists, and economists whose oeuvre is significant for philosophers even though we generally overlook them. This occurs because too often we deem worthy of philosophical interpretation only other philosophers and their investigations. But there are figures who have provided philosophers with new cultural, scientific, and political paradigms who are absent from our philosophical traditions. Although we could say they were philosophers without defining themselves as such, their works have often presented innovative concepts, meanings, and truths that give them the same ontological status as the work of other philosophers. For most continental thinkers—as analytic philosophers still believe our discipline is circumscribed exclusively to logical problems derived from mathematics and science—these figures are vital to understanding our past, present, and also future. David Ferrucci, who led the team that built IBM’s famed Watson computer, was elated when it beat the best-ever human “Jeopardy!” players in 2011, in a televised triumph for artificial intelligence.

David Ferrucci, who led the team that built IBM’s famed Watson computer, was elated when it beat the best-ever human “Jeopardy!” players in 2011, in a televised triumph for artificial intelligence. The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than

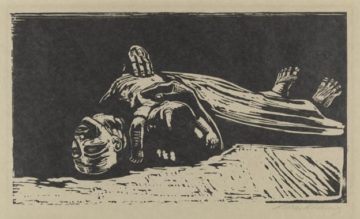

The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than  In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside.

In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside. The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies.

The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies. Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch.

Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch. From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project

From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project  There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music.

There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music. However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world.

However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world. THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR

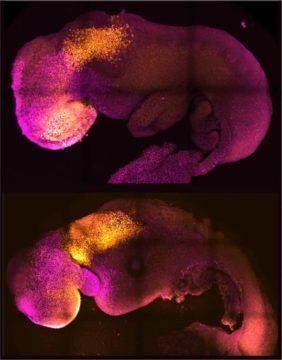

THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds.

The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds. Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):

Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):