Category: Recommended Reading

Frank Drake (1930 – 2022) Astronomer And Astrophysicist

Lars Vogt (1970 – 2022) Pianist And Conductor

Sunday Poem

All the Carefully Measured Seconds

Back then I still believed it was possible

to prevent certain things, until that hot afternoon.

It was the middle of grain harvest, August of ’54,

when Fred climbed down from his stalled combine

and took off to Montrose to buy a part.

Later I realized the part was a ruse of fate, like

something made up to get someone to a surprise party.

So many times I reran those last hours,

adding or subtracting a few seconds here or there.

Lingering a moment in the field, he could have

noticed the grain shiver as a cloud passed by,

he could have paused by the barn to admire the blue

and lavender flecks adorning the pigeon’s throats,

he could have stopped by the house to finger

the soft leaves of the African violets

on the sill, he could have slipped his arm

around Ella’s waist as she stood at the sink,

her hands in the dishwater.

But, he swatted the grain dust from his overalls

and climbed into his green Buick to keep

his appointment on Highway 38. Even then,

it was not too late. He could have floored

the car just this once, he could have let

the wind rush in, raising his sparse strands

of matted hair to dance in the breeze.

When I saw Fred’s car again, it looked as if

had been punched by the fist of some god

though surely not the same one who keeps

the earth spinning, the sun and moon rising,

passion ascending to fuse new life,

the rose unfolding with tenderness,

the worm tilling the orchard floor,

all the carefully measured seconds

adding up exactly to us.

by Josephine Redlin

from Ploughshares

publisher: Emerson College, Boston, Ma. 1995

‘The Case Against the Sexual Revolution’: How feminism let women down

Stephen Humphries in The Christian Science Monitor:

Statesman, majored in women’s studies. During her university years, she believed that hookup culture, pornography, and rough sex were all OK for consenting adults. A decade later, she’s changed her mind. Ms. Perry’s experience of working at a rape crisis center made her question the narrative she’d been taught that “rape is about power, not sex.” She then began to rethink other tenets of second-wave academic feminism.

Statesman, majored in women’s studies. During her university years, she believed that hookup culture, pornography, and rough sex were all OK for consenting adults. A decade later, she’s changed her mind. Ms. Perry’s experience of working at a rape crisis center made her question the narrative she’d been taught that “rape is about power, not sex.” She then began to rethink other tenets of second-wave academic feminism.

Ms. Perry is grateful that the birth control pill and modern contraceptives have given women greater control over their lives. But, she argues, it’s come at a cost. Modern feminism has encouraged women to feel empowered by having “sex like a man.” Ms. Perry believes that many women can’t just unyoke sex from emotion and a desire for committed relationships, including marriage. She says there’s a power imbalance in today’s sexual marketplace that can make women feel devalued.

More here.

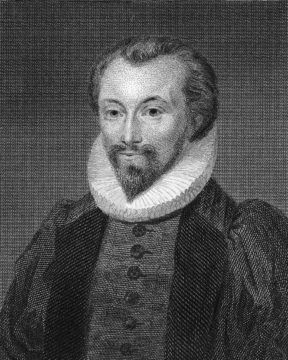

What John Donne Knew About Death Can Teach Us a Lot About Life

Katherine Rundell in The New York Times:

The power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man.

The power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man.

It was the spring of 1623, on the morning of Ascension Day, and Donne, long a struggling poet, had finally secured for himself celebrity, fortune and a captive audience. He had been appointed dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral two years before. He was 51, slim and amply bearded, and his preaching was famous across the whole of London. His congregation — merchants, aristocrats, actors in elaborate ruffs, the whole of the city’s elite — came to his sermons. Some carried paper and ink to write down his finest passages and take them home to relish and dissect them. Donne often wept in the pulpit, in joy and in sorrow, and his audience would weep with him.

That morning he was not preaching in his own church but 15 minutes’ easy walk across London at Lincoln’s Inn, in the center of town. Word went out: Wherever he was, people came flocking to hear him speak. But too many flocked, and as the crowd pushed closer to hear his words, some men were shoved to the ground, trampled and badly injured. A contemporary wrote in a letter, “Two or three were endangered, and taken up dead for the time.” There’s no record of Donne halting his sermon; so it’s not impossible that he kept going in his rich, authoritative voice as the bloodied men were carried off and out of sight.

More here.

Saturday, September 10, 2022

Is China’s Economy in Trouble?

Over at Foreign Policy:

China’s economy is projected to grow by 4 percent this year, a rate that many countries would envy. But with China’s track record, that number could actually be a harbinger of bad news. On today’s show, Adam and Cameron discuss the mechanics of the Chinese economy and why it’s unlike any other in the world.

Also on the show: Golf has been described as a game of strenuous idleness. How did it become an $84 billion industry in the United States?

Model Practitioner

Chris Lehmann in The Baffler:

Chris Lehmann in The Baffler:

WHEN I FIRST LAUNCHED my accidental career in journalism more than thirty years ago, as an intern at Mother Jones, one of my first assignments was to fact-check a column by Barbara Ehrenreich. I can still remember the topic: a characteristically biting and witty takedown of the daft notion of “reverse sexism” and some of its trademark turns of phrase. (A passing reference to men as the category of human responsible for hair growing out of their ears still makes me laugh whenever I’m forced to contemplate this unlovely truth.)

Most of all, though, the whole idea that I was trusted to work on this kind of thing—an energetic, incisive, and funny work of polemic journalism—gave me a direct and thrilling sense of the possibilities ahead on the dubious vocation I was then exploring. Given the generally squalid and chaotic condition of my mental life back then, the effect was roughly equivalent to hearing the clear and resounding sound of a tuning fork at the end of a command performance of Lou Reed’s dirge-and-noise opus Metal Machine Music.

More here.

The Inflated Promise of Science Education

Catarina Dutilh Novaes and Silvia Ivani in Boston Review:

Catarina Dutilh Novaes and Silvia Ivani in Boston Review:

Would the world be a better, or even a different, place if the public understood more of the scope and the limitations, the findings and the methods of science?” This question was taken up in 1985 by the UK’s Royal Society, one of the world’s oldest and most distinguished scientific bodies. A committee chaired by geneticist Sir Walter Bodmer answered in the affirmative: yes, a scientifically literate public would make the world a better place, facilitating public decision-making and increasing national prosperity.

Nearly four decades later, this view remains very popular—both within expert communities and without. The public, it is assumed, knows little about science: they are ignorant not just of scientific facts but of scientific methodology, the distinctive way scientific research is conducted. Moreover, this ignorance is supposed to be the primary source of widespread anti-science attitudes, generating fear and suspicion of scientists, scientific innovations, and public policy that is said to “follow the science.” The consequences are on wide display, from opposition to genetically modified foods to the anti-vax movement.

More here.

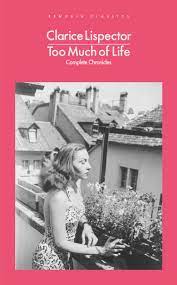

Too Much of Life by Clarice Lispector

Madoc Cairns at The Guardian:

From the age of seven, Clarice Lispector declared in a 1967 column for the newspaper Jornal do Brasil, she knew she was born to write. And write Lispector did. In a life foreshortened by illness – she died at the age of 56 – she wrote with impatient, impassioned energy, winning early fame for her short stories and novels. But it was her chronicles (crônicas) – newspaper columns published between 1967 and her death in 1977 and now translated into English for the first time – that made the Brazilian novelist a household name.

From the age of seven, Clarice Lispector declared in a 1967 column for the newspaper Jornal do Brasil, she knew she was born to write. And write Lispector did. In a life foreshortened by illness – she died at the age of 56 – she wrote with impatient, impassioned energy, winning early fame for her short stories and novels. But it was her chronicles (crônicas) – newspaper columns published between 1967 and her death in 1977 and now translated into English for the first time – that made the Brazilian novelist a household name.

Lispector was a successful journalist, but not a conventional one. Too Much of Life works in almost uninterrupted continuity with the writer’s fiction – stylistically and otherwise. Like her posthumous masterpiece, The Hour of the Star, her columns straddle realism, memoir, philosophy and politics, each dependent upon – and obscuring – the other.

more here.

Interview with Clarice Lispector – São Paulo, 1977

Chile’s Rejection

Camila Vergara in Sidecar:

Camila Vergara in Sidecar:

Pinochet and his legacy have proven hard to kill. The 2022 draft constitution – the most progressive constitution ever written in terms of socio-economic rights, gender equality, indigenous rights and the protection of nature – was rejected by almost 62% of voters in a national plebiscite on 4 September. How could Chileans, after rising up in October 2019 to demand a new constitution, then voting by an overwhelming majority to initiate the constituent process, reject the proposed draft? Why would they align with right-wing forces seeking to preserve the Pinochet constitution? This astonishing result surely demands a multi-causal explanation. Here I will focus on two of the most prominent ones: the right-wing disinformation campaign across traditional and social media, and the exclusion of the popular sectors from the constituent process, which I have highlighted in previous analyses.

Support for Rechazo (‘Reject’) was strongest in low-income municipalities, where turnout was also higher than in upper-class neighbourhoods. While in the 2020 plebiscite the opposition to the constituent process was led by the three wealthiest municipalities, this time around the poorest neighbourhoods turned out en masse to vote against the proposed draft. Also in contrast to 2020, voting was mandatory – with fines for non-compliance – which forced the popular sectors to cast a vote for fear of the pecuniary costs of abstention. Turnout increased substantially from 50% to 86%; and of the 5.4 million new votes cast, 96% opted to reject. In total, the draft constitution received only 4.8 million votes – one million less than voted in favour of redrafting two years earlier. This was not only a vote against the new constitutional text, however. It was also a rejection of Gabriel Boric’s administration and its parties: the ‘new left’ coalition including Frente Amplio, the Communist Party and the parties of the old Concertación. Apruebo (‘Approve’) was supported by roughly the same number of people that voted for Boric in the runoff against the far-right candidate José Antonio Kast in December 2021 – suggesting that he has been unable to expand his constituency since taking office.

More here.

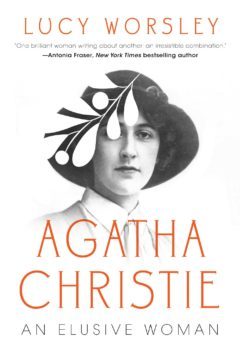

Agatha Christie’s Life of Mystery

Molly Young at the NYT:

Agatha Christie’s best books have crisp dialogue and high-velocity plots. The bad ones have a Mad Libs quality: feeble prose studded with blank spots into which you can picture the prolific Christie plugging a random “BODY PART” or “WEAPON.” In a 1971 study of English crime fiction, Colin Watson snickered that Christie “seems to have been well aware that intelligence and readership-potential are quite unrelated.”

Agatha Christie’s best books have crisp dialogue and high-velocity plots. The bad ones have a Mad Libs quality: feeble prose studded with blank spots into which you can picture the prolific Christie plugging a random “BODY PART” or “WEAPON.” In a 1971 study of English crime fiction, Colin Watson snickered that Christie “seems to have been well aware that intelligence and readership-potential are quite unrelated.”

Watson’s barb was unfair. Few readers turn to detective novels for complex cerebral rewards. Detective novels are games, and require a different method of evaluation (and construction) than works of capital-L Literature. Christie understood this.

more here.

Saturday Poem

The Edge of Sleep

And then I awoke, startled by

the slow walk of wind thru the trees.

The quilt crocheted by my mother

protects the bed, another layer

defying the cold on this quiet night.

I have never been afraid to dream,

but the numbers of the restless clock

remind me that time is never

finished, and this, an unremarkable truth.

I turn my head and look thru the window—

what I perceive to be enough

is merely a song I have forgotten the words to.

by Josh Mahler

from Bodega Magazine

Newfound Brain Switch Labels Experiences as Good or Bad

Ingrid Wickelgren in Scientific American:

For as long as she can remember, Kay Tye has wondered why she feels the way she does. Rather than just dabble in theories of the mind, however, Tye has long wanted to know what was happening in the brain. In college in the early 2000s, she could not find a class that spelled out how electrical impulses coursing through the brain’s trillions of connections could give rise to feelings. “There wasn’t the neuroscience course I wanted to take,” says Tye, who now heads a lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif. “It didn’t exist.” When she dedicated a chapter of her Ph.D. thesis to emotion, she was criticized for it, she recalls. The study of feelings had no place in behavioral neuroscience, she was told. Tye disagreed at the time, and she still does. “Where do we think emotions are being implemented—somewhere other than the brain?”

For as long as she can remember, Kay Tye has wondered why she feels the way she does. Rather than just dabble in theories of the mind, however, Tye has long wanted to know what was happening in the brain. In college in the early 2000s, she could not find a class that spelled out how electrical impulses coursing through the brain’s trillions of connections could give rise to feelings. “There wasn’t the neuroscience course I wanted to take,” says Tye, who now heads a lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif. “It didn’t exist.” When she dedicated a chapter of her Ph.D. thesis to emotion, she was criticized for it, she recalls. The study of feelings had no place in behavioral neuroscience, she was told. Tye disagreed at the time, and she still does. “Where do we think emotions are being implemented—somewhere other than the brain?”

Since then, Tye’s research team has taken a step toward deciphering the biological underpinnings of such ineffable experiences as loneliness and competitiveness. In a recent Nature study, she and her colleagues uncovered something fundamental: a molecular “switch” in the brain that flags an experience as positive or negative. Tye is no longer an outlier in pursuing these questions. Other researchers are thinking along the same lines. “If you have a brain response to anything that is important, how does it differentiate whether it is good or bad?” says Daniela Schiller, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who wasn’t involved in the Nature paper. “It’s a central problem in the field.”

More here.

Humanity was stagnant for millennia — then something big changed 150 years ago

Dylan Matthews in Vox:

“The 140 years from 1870 to 2010 of the long twentieth century were, I strongly believe, the most consequential years of all humanity’s centuries.” So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

“The 140 years from 1870 to 2010 of the long twentieth century were, I strongly believe, the most consequential years of all humanity’s centuries.” So argues Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, the new magnum opus from UC Berkeley professor Brad DeLong. It’s a bold claim. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years; the “long twentieth century” represents 0.05 percent of that history.

But to DeLong, who beyond his academic work is known for his widely read blog on economics, something incredible happened in that sliver of time that eluded our species for the other 99.95 percent of our history. Whereas before 1870, technological progress proceeded slowly, if at all, after 1870 it accelerated dramatically. And especially for residents of rich countries, this technological progress brought a world of unprecedented plenty. DeLong reports that in 1870, an average unskilled male worker living in London could afford 5,000 calories for himself and his family on his daily wages. That was more than the 3,000 calories he could’ve afforded in 1600, a 66 percent increase — progress, to be sure. But by 2010, the same worker could afford 2.4 million calories a day, a nearly five hundred fold increase.

More here.

Friday, September 9, 2022

How to lie (in mathematics) using visual proofs

Americans think they know a lot about politics – and it’s bad for democracy that they’re so often wrong in their confidence

Ian Anson in The Conversation:

Over the past five years, I have studied the phenomenon of what I call “political overconfidence.” My work, in tandem with other researchers’ studies, reveals the ways it thwarts democratic politics.

Over the past five years, I have studied the phenomenon of what I call “political overconfidence.” My work, in tandem with other researchers’ studies, reveals the ways it thwarts democratic politics.

Political overconfidence can make people more defensive of factually wrong beliefs about politics. It also causes Americans to underestimate the political skill of their peers. And those who believe themselves to be political experts often dismiss the guidance of real experts.

Political overconfidence also interacts with political partisanship, making partisans less willing to listen to peers across the aisle.

The result is a breakdown in the ability to learn from one another about political issues and events.

More here.

The Hunger | ContraPoints

Mikhail Gorbachev And His Generation

Gregory Afinogenov at n+1:

Gorbachev was born in 1931, on the other side of the revolutionary chasm. Though famine and terror made their appearances in his childhood, he entered adulthood after the most traumatic periods of Soviet history had already passed. Graduating from university two years after Stalin’s death, Gorbachev became part of a generation of starry-eyed young utopians. As their elders began to make their peace with the indefinite deferral of communism, young people were determined to see it in their lifetimes. In 1967, a group of youth in the city of Novorossiisk sank a time capsule into the Black Sea filled with letters addressed to the anticipated space-faring communist future of 2017. A schoolgirl named Olga wrote, “We dream of communism, of a time when you can eat ice cream and go to the movies for free, when machines will do our homework while our teachers will be patient robots. You live under communism, and I will live under communism too, with the only difference being that you will be as old as I was fifty years ago.” Gorbachev, on the older end of this generation, was then just beginning his rapid political ascent in the nearby city of Stavropol.

Gorbachev was born in 1931, on the other side of the revolutionary chasm. Though famine and terror made their appearances in his childhood, he entered adulthood after the most traumatic periods of Soviet history had already passed. Graduating from university two years after Stalin’s death, Gorbachev became part of a generation of starry-eyed young utopians. As their elders began to make their peace with the indefinite deferral of communism, young people were determined to see it in their lifetimes. In 1967, a group of youth in the city of Novorossiisk sank a time capsule into the Black Sea filled with letters addressed to the anticipated space-faring communist future of 2017. A schoolgirl named Olga wrote, “We dream of communism, of a time when you can eat ice cream and go to the movies for free, when machines will do our homework while our teachers will be patient robots. You live under communism, and I will live under communism too, with the only difference being that you will be as old as I was fifty years ago.” Gorbachev, on the older end of this generation, was then just beginning his rapid political ascent in the nearby city of Stavropol.

more here.