Peter Wollen at New Left Review:

The exile Bertolt Brecht arrived in Los Angeles on 21 July 1941, and was taken by friends to a small house in Hollywood found for him by the director William Dieterle and his wife. Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane had recently premiered in New York, on 1 May. On his previous short visit to the United States, in connection with the New York opening of his play The Mother in 1935, Brecht had met the composer Marc Blitzstein through Hanns Eisler, who was teaching at the New School for Social Research. Blitzstein had played one of his new songs to Brecht and Brecht had advised Blitzstein to go ahead and write a full-scale opera. The result was Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock, which was dedicated to Brecht and directed on stage by Orson Welles. A decade later, in 1946, Brecht saw Welles’s production of Cole Porter’s Around the World in Boston and went backstage afterwards to announce that, ‘This is the greatest thing I have seen in American theatre. This is wonderful. This is what theatre should be.’ Subsequently Brecht tried to persuade Welles to direct his own new play, Galileo. Welles was keen to do it but negotiations broke down over the role of Mike Todd, with whom Welles had become involved as his producer. Instead, it was Joseph Losey who directed Galileo.

The exile Bertolt Brecht arrived in Los Angeles on 21 July 1941, and was taken by friends to a small house in Hollywood found for him by the director William Dieterle and his wife. Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane had recently premiered in New York, on 1 May. On his previous short visit to the United States, in connection with the New York opening of his play The Mother in 1935, Brecht had met the composer Marc Blitzstein through Hanns Eisler, who was teaching at the New School for Social Research. Blitzstein had played one of his new songs to Brecht and Brecht had advised Blitzstein to go ahead and write a full-scale opera. The result was Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock, which was dedicated to Brecht and directed on stage by Orson Welles. A decade later, in 1946, Brecht saw Welles’s production of Cole Porter’s Around the World in Boston and went backstage afterwards to announce that, ‘This is the greatest thing I have seen in American theatre. This is wonderful. This is what theatre should be.’ Subsequently Brecht tried to persuade Welles to direct his own new play, Galileo. Welles was keen to do it but negotiations broke down over the role of Mike Todd, with whom Welles had become involved as his producer. Instead, it was Joseph Losey who directed Galileo.

more here.

Democracy is the worst form of government,”

Democracy is the worst form of government,”  Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new  Unlike most modern European languages, English designates book-length works of prose fiction with the term “novel”. Imported sometime in the mid-16th century from Italy – where novella had been coined to describe the short stories collected in Boccaccio’s Decameron 200 years before – and extended to its more or less current sense in the 17th century, the word retains a semantic filiation to that other child of the age of print, the newspaper, and thus to the concepts of information and modernity itself. Until the Austenite revolution of 1811 the novel often cloaked itself in the trappings of genres later classified as

Unlike most modern European languages, English designates book-length works of prose fiction with the term “novel”. Imported sometime in the mid-16th century from Italy – where novella had been coined to describe the short stories collected in Boccaccio’s Decameron 200 years before – and extended to its more or less current sense in the 17th century, the word retains a semantic filiation to that other child of the age of print, the newspaper, and thus to the concepts of information and modernity itself. Until the Austenite revolution of 1811 the novel often cloaked itself in the trappings of genres later classified as  An artificial intelligence model built by Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear scientists was shown to be significantly more accurate than doctors at diagnosing pediatric ear infections in the first head-to-head evaluation of its kind, the research team working to develop the model for clinical use reported.

An artificial intelligence model built by Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear scientists was shown to be significantly more accurate than doctors at diagnosing pediatric ear infections in the first head-to-head evaluation of its kind, the research team working to develop the model for clinical use reported. A sizable literature tracing back to Richard Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style (1964) argues that Republicans and conservatives are more likely to believe conspiracy theories than Democrats and liberals. However, the evidence for this proposition is mixed. Since conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with dangerous orientations and behaviors, it is imperative that social scientists better understand the connection between conspiracy theories and political orientations. Employing 20 surveys of Americans from 2012 to 2021 (total n = 37,776), as well as surveys of 20 additional countries spanning six continents (total n = 26,416), we undertake an expansive investigation of the asymmetry thesis. First, we examine the relationship between beliefs in 52 conspiracy theories and both partisanship and ideology in the U.S.; this analysis is buttressed by an examination of beliefs in 11 conspiracy theories across 20 more countries. In our second test, we hold constant the content of the conspiracy theories investigated—manipulating only the partisanship of the theorized villains—to decipher whether those on the left or right are more likely to accuse political out-groups of conspiring. Finally, we inspect correlations between political orientations and the general predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories over the span of a decade.

A sizable literature tracing back to Richard Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style (1964) argues that Republicans and conservatives are more likely to believe conspiracy theories than Democrats and liberals. However, the evidence for this proposition is mixed. Since conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with dangerous orientations and behaviors, it is imperative that social scientists better understand the connection between conspiracy theories and political orientations. Employing 20 surveys of Americans from 2012 to 2021 (total n = 37,776), as well as surveys of 20 additional countries spanning six continents (total n = 26,416), we undertake an expansive investigation of the asymmetry thesis. First, we examine the relationship between beliefs in 52 conspiracy theories and both partisanship and ideology in the U.S.; this analysis is buttressed by an examination of beliefs in 11 conspiracy theories across 20 more countries. In our second test, we hold constant the content of the conspiracy theories investigated—manipulating only the partisanship of the theorized villains—to decipher whether those on the left or right are more likely to accuse political out-groups of conspiring. Finally, we inspect correlations between political orientations and the general predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories over the span of a decade. PRESIDENT LAWRENCE S. BACOW

PRESIDENT LAWRENCE S. BACOW Terri Apter, a psychologist, still remembers the time she explained to an 18-year-old how the teenage brain works: “So that’s why I feel like my head’s exploding!” the teen replied, with pleasure. Parents and teachers of teens may recognise that sensation of dealing with a highly combustible mind. The teenage years can feel like a shocking transformation – a turning inside out of the mind and soul that renders the person unrecognisable from the child they once were. There’s the hard-to-control mood swings, identity crises and the hunger for social approval, a newfound taste for risk and adventure, and a seemingly complete inability to think about the future repercussions of their actions.

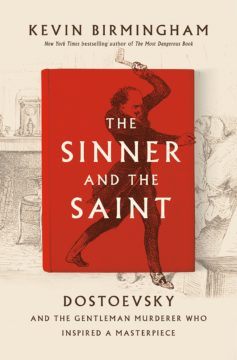

Terri Apter, a psychologist, still remembers the time she explained to an 18-year-old how the teenage brain works: “So that’s why I feel like my head’s exploding!” the teen replied, with pleasure. Parents and teachers of teens may recognise that sensation of dealing with a highly combustible mind. The teenage years can feel like a shocking transformation – a turning inside out of the mind and soul that renders the person unrecognisable from the child they once were. There’s the hard-to-control mood swings, identity crises and the hunger for social approval, a newfound taste for risk and adventure, and a seemingly complete inability to think about the future repercussions of their actions. Dostoevsky’s own fixation on Lacenaire and his crime, which he declared “more exciting than all possible fiction,” is the focus of Birmingham’s consistently immersing The Sinner and the Saint. The Lacenaire who emerges from these pages is a subtle, ambiguous, sometimes insidiously appealing challenger to a corrupt established order. “I come to preach the religion of fear to the elite,” he announced at his trial, sounding a bit like a prototype Charles Manson. Almost anyone could write a gripping account of Lacenaire’s particular offense, but it took a writer of Dostoevsky’s gifts, not to mention of his experience in Semyonovosky Square, to painstakingly lead his readers on a course between the extremes of revulsion and fascination. What really interested Dostoevsky, and interests us, is the morality of crime, and how people can come to rationalize even the most depraved homicidal frenzy. He’s an author who takes risks, makes us both laugh and wince, and (depending on the translator’s art) writes like an angel with a devilish sense of humor.

Dostoevsky’s own fixation on Lacenaire and his crime, which he declared “more exciting than all possible fiction,” is the focus of Birmingham’s consistently immersing The Sinner and the Saint. The Lacenaire who emerges from these pages is a subtle, ambiguous, sometimes insidiously appealing challenger to a corrupt established order. “I come to preach the religion of fear to the elite,” he announced at his trial, sounding a bit like a prototype Charles Manson. Almost anyone could write a gripping account of Lacenaire’s particular offense, but it took a writer of Dostoevsky’s gifts, not to mention of his experience in Semyonovosky Square, to painstakingly lead his readers on a course between the extremes of revulsion and fascination. What really interested Dostoevsky, and interests us, is the morality of crime, and how people can come to rationalize even the most depraved homicidal frenzy. He’s an author who takes risks, makes us both laugh and wince, and (depending on the translator’s art) writes like an angel with a devilish sense of humor. I did not expect that studying a childhood discipline would lead me to wonder about divine matters, but the possibility of a divine entity is threaded throughout mathematics, which, in its essence, so far as I can tell, is a mystical pursuit, an attempt to claim territory and define objects seen only in the minds of people doing mathematics. Why do I care about abstract possibilities and especially about God, when I have no idea what such a thing might be? A concept? An actual entity? Something hidden but accessible, or forever out of reach? Something once present and now gone? Something that ancient people appear to have experienced at close hand?

I did not expect that studying a childhood discipline would lead me to wonder about divine matters, but the possibility of a divine entity is threaded throughout mathematics, which, in its essence, so far as I can tell, is a mystical pursuit, an attempt to claim territory and define objects seen only in the minds of people doing mathematics. Why do I care about abstract possibilities and especially about God, when I have no idea what such a thing might be? A concept? An actual entity? Something hidden but accessible, or forever out of reach? Something once present and now gone? Something that ancient people appear to have experienced at close hand? When the first baby to be conceived using a technique that mixes genetic material from three people

When the first baby to be conceived using a technique that mixes genetic material from three people  While his filmography is now iconic — his mainstream hit Hairspray (1988) has spawned both a remake and an acclaimed musical — the 76-year-old provocateur hasn’t made a picture since 2004. Waters has instead occupied himself with other projects, namely fine art and writing. His more recent books include Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America (2014) and Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder (2019). The so-called “filth elder” has now written his first novel, Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance, released this May by Macmillan Publishers.

While his filmography is now iconic — his mainstream hit Hairspray (1988) has spawned both a remake and an acclaimed musical — the 76-year-old provocateur hasn’t made a picture since 2004. Waters has instead occupied himself with other projects, namely fine art and writing. His more recent books include Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America (2014) and Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder (2019). The so-called “filth elder” has now written his first novel, Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance, released this May by Macmillan Publishers. The human brain is an amazing computing machine. Weighing only three pounds or so, it can process information a thousand times faster than the fastest supercomputer, store a thousand times more information than a powerful laptop, and do it all using no more energy than a 20-watt lightbulb.

The human brain is an amazing computing machine. Weighing only three pounds or so, it can process information a thousand times faster than the fastest supercomputer, store a thousand times more information than a powerful laptop, and do it all using no more energy than a 20-watt lightbulb. In a speech on July 23, 2022, before the Conservative Political Action Committee, or CPAC, Sen. Ted Cruz

In a speech on July 23, 2022, before the Conservative Political Action Committee, or CPAC, Sen. Ted Cruz  Physics professor Wilhelm Röntgen made an unexpected discovery when he blasted electrons from one electrode to another:

Physics professor Wilhelm Röntgen made an unexpected discovery when he blasted electrons from one electrode to another: