Category: Recommended Reading

China’s New Direction

Paola Subacchi in Project Syndicate:

China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “responsible stakeholder” in the international institutions that emerged after World War II and survived the Cold War. But now, many worry that China is “an illiberal state seeking leadership in a liberal world order,” as former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker puts it in Global Discord. The question, then, is how liberal democracies with market economies should deal with such a state when it becomes a systematically important power.

China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “responsible stakeholder” in the international institutions that emerged after World War II and survived the Cold War. But now, many worry that China is “an illiberal state seeking leadership in a liberal world order,” as former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker puts it in Global Discord. The question, then, is how liberal democracies with market economies should deal with such a state when it becomes a systematically important power.

None of the four books reviewed here provides a convincing answer – but that may be because the China question does not admit of one. Instead, each author offers a clear narrative of China’s transformation from a poor developing country to the main global competitor to the West.

More here.

The Difficult Task of Erasing…Twentieth-Century Art – Yves-Alain Bois

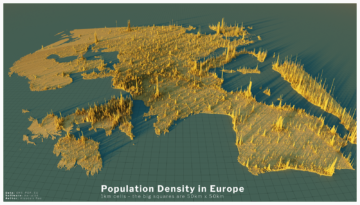

The World’s Largest Population Density Centers

Alasdair Rae at Visual Capitalist:

It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of 8 billion people, but this series of population density maps makes the picture abundantly clear. Created using the EU’s population density data and mapping tool Aerialod by Alasdair Rae, the 3D-rendered maps highlight demographic trends and geographic constraints.

It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of 8 billion people, but this series of population density maps makes the picture abundantly clear. Created using the EU’s population density data and mapping tool Aerialod by Alasdair Rae, the 3D-rendered maps highlight demographic trends and geographic constraints.

Though they appear topographical and even resemble urban areas, the maps visualize population density in squares. The height of each bar represents the number of people living in that specific square, with the global map displaying 2km x 2km squares and subsequent maps displaying 1km x 1km squares. Each region and country tells its own demographic story, but the largest population clusters are especially illuminating.

more here.

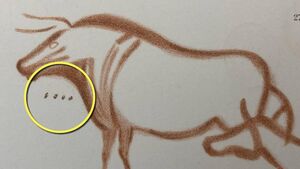

Londoner Solves 20,000-Year Ice Age Drawings Mystery

at the BBC:

A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings.

A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings.

Ben Bacon analysed 20,000-year-old markings on the drawings, concluding they could refer to a lunar calendar. It led to a specialist team proving early Europeans made notes about the timing of animals’ reproductive cycles. Mr Bacon said it was “surreal” to work out for the first time what hunter-gatherers were saying. Cave paintings of animals such as reindeer, fish and cattle have been found in caves across Europe. But archaeologists had been stumped by the meaning of dots and other marks on the paintings. So Mr Bacon decided he would try to decode them.

more here.

Friday Poem

Stone

De piedra, sangre.

I make my own heaven. I drag it out of the streets, and

inhospitable terrains. I mixed “tabique”, brick, mortar with

my hands, kneading,

I need, to make my own heaven.

It is clandestine, in broad daylight.

It’s microwave popcorn, from Costco, because Costco can

cross the border as many times as it wants and it has never

been asked to go back to where it came from. Not in this

kitchen, scrubbed so clean, with bleach, that the roaches have

to ask permission to scatter out onto the floor.

Sulema and I, don’t flinch. She has figured me out. We know

we have lived some shit and now, it takes more than a

cockroach to keep us from moving, forward.

Fuck the roaches, the military, the long nights and even

longer days. There is popcorn to be made,

a courtyard of children waiting for it.

Baby girl walks in to check on our progress. She is waiting

impatiently for popcorn, the smell of butter making its way

around the shelter, La Casa.

The house is built on a solid foundation of Goodyear tires,

and unpacked, repacked, suitcases, unpacked, repacked plans.

Today, there is popcorn.

All that matters is today,

For my sake, not Sulema’s.

The flowerbeds, and the upside-down Christmas trees, drying

out in the sun are beautiful.

I will remember them, when I am warm by a campfire,

watching my children for signs of a chill.

I will remember them,

determined,

uneven steps, protruding out of a hillside, going wherever

they need to go.

Wherever they need to go.

There is no going back.

Sulema and I both know this, standing in the hot kitchen of

the TJ shelter, it is obvious.

It is a beautiful truth, it takes hesitation and beats it down,

into the floor.

We danced on it.

by Aideed Medina

from Split This Rock

How companionship and an active social life can improve the lives of India’s elderly

Chawla and Chakraborty in Scroll.In:

You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.”

You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.”

When we ask Chandrika Desai how she stays connected to people, she has a hearty laugh. “It’s my personality,” she says. Desai is a jovial 74-year-old who epitomises how important social engagement could be. But like she tells us, passively becoming part of a group is not the only way to do it. You need to be active at your end, too. Every morning, Desai sits with a list. She has a large network of family and friends, and each morning she calls different people. “I make an effort to reach out,” says Desai who lives on her own, leads her own life but is deeply connected to her two children who live overseas.

More here.

Revolutionary Cancer Vaccine Simultaneously Kills and Prevents Brain Tumors

From SciTechDaily:

Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, investigators have developed a new cell therapy approach to eliminate established tumors and induce long-term immunity, training the immune system so that it can prevent cancer from recurring. The team tested their dual-action, cancer-killing vaccine in an advanced mouse model of the deadly brain cancer glioblastoma, with promising results. Findings are published in Science Translational Medicine.

Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, investigators have developed a new cell therapy approach to eliminate established tumors and induce long-term immunity, training the immune system so that it can prevent cancer from recurring. The team tested their dual-action, cancer-killing vaccine in an advanced mouse model of the deadly brain cancer glioblastoma, with promising results. Findings are published in Science Translational Medicine.

“Our team has pursued a simple idea: to take cancer cells and transform them into cancer killers and vaccines,” said corresponding author Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, director of the Center for Stem Cell and Translational Immunotherapy (CSTI) and the vice chair of research in the Department of Neurosurgery at the Brigham and faculty at Harvard Medical School and Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI). “Using gene engineering, we are repurposing cancer cells to develop a therapeutic that kills tumor cells and stimulates the immune system to both destroy primary tumors and prevent cancer.”

More here.

Thursday, January 5, 2023

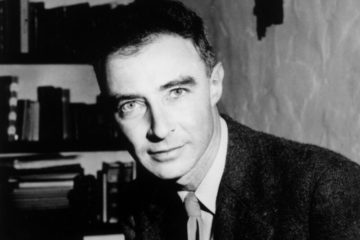

J. Robert Oppenheimer cleared of “black mark” against his name after 68 years

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer has finally received some form of justice just in time for Christmas, according to a December 16 article in the New York Times. US Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm released a statement nullifying the controversial decision that badly tarnished the late physicist’s reputation, declaring it to be the result of a “flawed process” that violated the AEC’s own regulations.

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer has finally received some form of justice just in time for Christmas, according to a December 16 article in the New York Times. US Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm released a statement nullifying the controversial decision that badly tarnished the late physicist’s reputation, declaring it to be the result of a “flawed process” that violated the AEC’s own regulations.

Science historian Alex Wellerstein of Stevens Institute of Technology told the New York Times that the exoneration was long overdue. “I’m sure it doesn’t go as far as Oppenheimer and his family would have wanted,” he said. “But it goes pretty far. The injustice done to Oppenheimer doesn’t get undone by this. But it’s nice to see some response and reconciliation even if it’s decades too late.”

More here.

Richard Dawkins on Steven Pinker’s new book, “Rationality”

Richard Dawkins in Skeptical Inquirer:

Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too.

Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too.

And now Rationality. In the final chapter of this book, Pinker raises the serious, even baffling, question of how it could ever have been necessary to mount an argument against slavery, against drawing and quartering, against breaking on the wheel, or against burning at the stake. Isn’t the case against slavery obvious? Nevertheless, it had to be made. One could ask the same question about the justification of rationality. How is it possible that rationality needs an advocate? Isn’t it obvious?

More here.

‘It was a set-up, we were fooled’: the coal mine that ate an Indian village

Ankur Paliwal in The Guardian:

The village was located in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, on the edge of the dense Hasdeo Arand forest. One of India’s few pristine and contiguous tracts of forest, Hasdeo Arand sprawls across more than 1,500 sq km. The land is home to rare plants such as epiphytic orchids and smilax, endangered animals such as sloth bears and elephants, and sal trees so tall they seem to brush against the sky.

The village was located in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, on the edge of the dense Hasdeo Arand forest. One of India’s few pristine and contiguous tracts of forest, Hasdeo Arand sprawls across more than 1,500 sq km. The land is home to rare plants such as epiphytic orchids and smilax, endangered animals such as sloth bears and elephants, and sal trees so tall they seem to brush against the sky.

The forest also contains an estimated 5bn tonnes of coal. This coal is located close to the surface, which makes it easy to mine. The federal government has divided the region into 23 “coal blocks”, six of which it has approved for mining. The Adani Group has bagged the contracts to mine four of those six, including the one that encompasses Kete and adjoining villages. The construction of these mines will destroy at least 1,898 hectares of forest land. The specific coal block under Kete has about 450m tonnes of coal, worth about $5bn.

More here.

Weird metal that’s also glass is insanely bouncy

Thursday Poem

Diaspora

If the meaning of the prayer was not passed down to you,

find it through holier means than translation.

Cling to the rhythm instead.

If you were not taught the rhythm, memorize the clang

of knife against yam against wooden cutting board.

Keep it ringing, ringing in your ears.

If not the ring,

then the Bombay jazz club

and its green lanterns swaying in the long, long night

If you were not given the religion, then at least

Boompa’s rosary beads,

with their memories

indented in thick amber,

the gold Zarathustra hanging from a neck

and tattooed on a sunburnt back.

If the traditions were never taught to you,

then cling to tea time always served at 2pm.

Display the cups and remember

elders do not take their tea with sugar,

like you do.

You have only a fraction of their blood.

You thicken your water with milk.

If home did not fit in the carry on compartment,

then the sprigs of lemongrass from the garden will do.

The tea bags brought from India will do.

The reusable garland will do.

The passport’s golden lions

show a compass of 3 directions.

The fourth will do, too.

With its back facing you,

and its open jaws the homeland.

If the orthodox genealogy did not show up to the altar

of any of the son’s weddings, identity will celebrate

the melting pot mothers. Inheritance

blooms a grateful garland

around the brownish baby’s plump smile.

Her laughter, an anthem.

Her heartbeat, a golden rhythm.

by Azura Tyabji

from Split This Rock

.

The ‘breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers

McKenzie Prillaman in Nature:

The hotel ballroom was packed to near capacity with scientists when Susan Yanovski arrived. Despite being 10 minutes early, she had to manoeuvre her way to one of the few empty seats near the back. The audience at the ObesityWeek conference in San Diego, California, in November 2022, was waiting to hear the results of a hotly anticipated drug trial. The presenters — researchers affiliated with pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, based in Bagsværd, Denmark — did not disappoint. They described the details of an investigation of a promising anti-obesity medication in teenagers, a group that is notoriously resistant to such treatment. The results astonished researchers: a weekly injection for almost 16 months, along with some lifestyle changes, reduced body weight by at least 20% in more than one-third of the participants1. Previous studies2,3 had shown that the drug, semaglutide, was just as impressive in adults.

The hotel ballroom was packed to near capacity with scientists when Susan Yanovski arrived. Despite being 10 minutes early, she had to manoeuvre her way to one of the few empty seats near the back. The audience at the ObesityWeek conference in San Diego, California, in November 2022, was waiting to hear the results of a hotly anticipated drug trial. The presenters — researchers affiliated with pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, based in Bagsværd, Denmark — did not disappoint. They described the details of an investigation of a promising anti-obesity medication in teenagers, a group that is notoriously resistant to such treatment. The results astonished researchers: a weekly injection for almost 16 months, along with some lifestyle changes, reduced body weight by at least 20% in more than one-third of the participants1. Previous studies2,3 had shown that the drug, semaglutide, was just as impressive in adults.

The presentation concluded like no other at the conference, says Yanovski, co-director of the Office of Obesity Research at the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland. Sustained applause echoed through the room “like you were at a Broadway show”, she says.

More here.

How We Learned to Be Lonely

Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic:

Communities can be amazingly resilient after traumas. Londoners banded together during the German Blitz bombings of World War II, and rebuilt the city afterward. When I visited the Thai island of Phuket six months after the 2004 tsunami killed thousands in the region and displaced even more, I found a miraculous recovery in progress, and in many places, little remaining evidence of the tragedy. It was inspirational.

Communities can be amazingly resilient after traumas. Londoners banded together during the German Blitz bombings of World War II, and rebuilt the city afterward. When I visited the Thai island of Phuket six months after the 2004 tsunami killed thousands in the region and displaced even more, I found a miraculous recovery in progress, and in many places, little remaining evidence of the tragedy. It was inspirational.

Going from surviving to thriving is crucial for healing and growth after a disaster, and scholars have shown that it can be a common experience. Often, the worst conditions bring out the best in people as they work together for their own recovery and that of their neighbors. COVID-19 appears to be resistant to this phenomenon, unfortunately. The most salient social feature of the pandemic was how it forced people into isolation; for those fortunate enough not to lose a loved one, the major trauma it created was loneliness. Instead of coming together, emerging evidence suggests that we are in the midst of a long-term crisis of habitual loneliness, in which relationships were severed and never reestablished. Many people—perhaps including you—are still wandering alone, without the company of friends and loved ones to help rebuild their life.

More here.

On Eva Brann’s “Pursuits of Happiness”

Peggy Ellsberg at the LARB:

Brann’s new book sweeps across the vast range of things that hold her interest. It thus invites us to enjoy the life of the mind and to live from our highest selves. A thoughtful encounter with this book will make you, I swear, a better person. The book includes chapters on Thing-Love, the Aztecs, Athens, Jane Austen, Plato, Wisdom, the Idea of the Good. The first half provides an on-ramp to the chapter titled “On Being Interested,” which falls in the dead center of the book. This central chapter serves as more than a cog in the wheel: it is an ars poetica. Addressing issues of attention, focus, and interest itself, as well as how and where to deploy these functions throughout our lives, “Being Interested” offers a solution for any seeker intrigued by the notion that happiness is not an accident but a vocation. Brann characterizes the pursuit of happiness as “ontological optimism […] to be maintained in the face of reality’s recalcitrance.” In her 2010 book Homage to Americans: Mile-High Meditations, Close Readings, and Time-Spanning Speculations, Brann recounts her experience of waiting for a delayed flight at the Denver Airport. Rather than whining about the tedium and soul-sucking banality of the event, she turns her exquisite attention to the actual experience of “waiting.” Possessed of a consistent ability to enjoy, Brann seems literally incapable of boredom.

Brann’s new book sweeps across the vast range of things that hold her interest. It thus invites us to enjoy the life of the mind and to live from our highest selves. A thoughtful encounter with this book will make you, I swear, a better person. The book includes chapters on Thing-Love, the Aztecs, Athens, Jane Austen, Plato, Wisdom, the Idea of the Good. The first half provides an on-ramp to the chapter titled “On Being Interested,” which falls in the dead center of the book. This central chapter serves as more than a cog in the wheel: it is an ars poetica. Addressing issues of attention, focus, and interest itself, as well as how and where to deploy these functions throughout our lives, “Being Interested” offers a solution for any seeker intrigued by the notion that happiness is not an accident but a vocation. Brann characterizes the pursuit of happiness as “ontological optimism […] to be maintained in the face of reality’s recalcitrance.” In her 2010 book Homage to Americans: Mile-High Meditations, Close Readings, and Time-Spanning Speculations, Brann recounts her experience of waiting for a delayed flight at the Denver Airport. Rather than whining about the tedium and soul-sucking banality of the event, she turns her exquisite attention to the actual experience of “waiting.” Possessed of a consistent ability to enjoy, Brann seems literally incapable of boredom.

more here.

Eva Brann: Why Read?

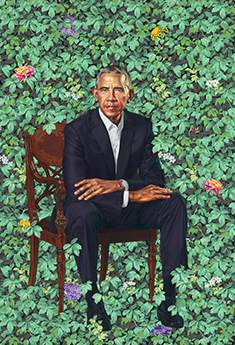

The Kehinde Wiley Empire

Julian Lucas at The New Yorker:

Few have won bigger than Wiley, whose good fortune has taken him from an enfant terrible of the early two-thousands, when he became known for transfiguring hip-hop style into the idiom of the Old Masters, to one of the most influential figures in global Black culture. He was already collected by Alicia Keys and the Smithsonian when his official portrait of Obama, unveiled in 2018, sparked a nationwide pilgrimage. Now, following the success of Black Rock Senegal, a lavish arts residency he’s established in Dakar—soon to be joined by a second location, in Nigeria—Wiley is shifting the art world’s center of gravity toward Africa with a determination that combines the institution-founding fervor of Booker T. Washington and the stagecraft of Willy Wonka. No longer just painting power, he’s building it.

In Brussels, Wiley was searching for models to confect into the image of royalty for a site-specific show proposed by the city’s Oldmasters Museum. The challenge was familiar.

more here.

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

New Vonnegut Documentary is Moving But Distracted

John Griswold in The Common Reader:

IFC Films has released a new documentary on Kurt Vonnegut, co-directed by Robert Weide, who in the process of filming Vonnegut over decades created a close relationship with the writer. The film traces this connection, even as it shows Weide’s failure to make his original conception of the documentary—for 40 years.

IFC Films has released a new documentary on Kurt Vonnegut, co-directed by Robert Weide, who in the process of filming Vonnegut over decades created a close relationship with the writer. The film traces this connection, even as it shows Weide’s failure to make his original conception of the documentary—for 40 years.

Weide has won three Emmys, including for his work on Curb Your Enthusiasm, and has made previous documentaries on comedians he loves, such as Lenny Bruce, the Marx Brothers, WC Fields, and Woody Allen. Those subjects contain darker impulses, and this new film plays off the seeming dichotomy between the comedic and the angry/traumatized/depressed, but it does not go very deep in this.

Vonnegut, following Arthur Koestler, thought the human neocortex an evolutionary mistake that led to suffering and extinction, but he insisted we have the free will to be more moral. When his hope for better behavior fails he makes jokes, and when those fail due to grim evidence, he can say only, “So it goes,” as he does a hundred times in Slaughterhouse-Five.

More here.

Forget about fluency and how languages are taught at school: as an adult learner you can take a whole new approach

John Gallagher in Psyche:

One of the first things I learnt to say in Dutch was ‘we beat them to death with sticks’. Not exactly standard fare for the first week of language classes, but then again this wasn’t an ordinary language class. As a historian working with 16th- and 17th-century documents, I was taking a specialised class to learn to read the Dutch of the period – so, instead of learning how to talk about hobbies or ask directions to the train station, we jumped straight into texts from the so-called Golden Age of the Netherlands.

One of the first things I learnt to say in Dutch was ‘we beat them to death with sticks’. Not exactly standard fare for the first week of language classes, but then again this wasn’t an ordinary language class. As a historian working with 16th- and 17th-century documents, I was taking a specialised class to learn to read the Dutch of the period – so, instead of learning how to talk about hobbies or ask directions to the train station, we jumped straight into texts from the so-called Golden Age of the Netherlands.

As someone who had learnt a few languages before, this was a whole new experience for me. I was used to the kind of language learning that might be familiar from school: an orderly progression through the basics of grammar, the steady building-up of vocabulary, some basic dialogues on tape or practised with a classmate. But, with Dutch, I had to change my methods and find new learning aids that worked for this project.

More here.