Hillary Angelo at Harper’s Magazine:

In a 1947 article for this magazine, the essayist and historian Bernard DeVoto warned of the “forever-recurrent lust to liquidate the West.” “Almost invariably the first phase was a ‘rush,’ ” he wrote. “Those who participated were practically all Easterners whose sole desire was to wash out of Western soil as much wealth as they could and take it home.” For DeVoto, the New Deal offered a chance for more sustainable and locally beneficial uses of Western resources, but, in the end, Eastern capital was “able to direct much of this development in the old pattern.”

In a 1947 article for this magazine, the essayist and historian Bernard DeVoto warned of the “forever-recurrent lust to liquidate the West.” “Almost invariably the first phase was a ‘rush,’ ” he wrote. “Those who participated were practically all Easterners whose sole desire was to wash out of Western soil as much wealth as they could and take it home.” For DeVoto, the New Deal offered a chance for more sustainable and locally beneficial uses of Western resources, but, in the end, Eastern capital was “able to direct much of this development in the old pattern.”

When outsiders try to describe the solar rush, they reach for historical analogies: the 1889 Oklahoma land rush; the early-twentieth-century eucalyptus boom that tore up the desert; housing speculation and development in the Aughts. But in Beatty such boom-and-bust cycles—the sort they’ve been trying to break out of for the past ten years—are part of the everyday landscape. In the desert, the past is close to the surface.

more here.

In August 2022, two research groups published papers in

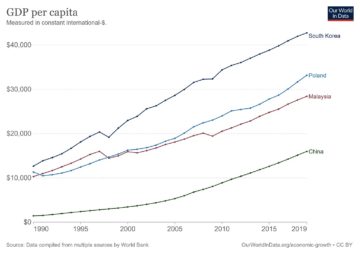

In August 2022, two research groups published papers in  The generally acknowledged development champion of the modern world is South Korea. Joe Studwell, the author of

The generally acknowledged development champion of the modern world is South Korea. Joe Studwell, the author of  So who is Janelle Monáe? Since she emerged on the music scene, she’s been less a pop star than a world-builder, refracting herself through sci-fi and Afrofuturist imagery. Her first EP, “Metropolis: The Chase Suite,” from 2007, drew on Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist classic and cast Monáe as her android alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. With her tuxedos and protruding pompadours, she was a glam retro-futurist androgyne, and her three studio albums—“The ArchAndroid” (2010), “The Electric Lady” (2013), and “Dirty Computer” (2018)—leaned into her funk-robot persona. “I’m a cyber-girl without a face, a heart, or a mind,” she sang on one track. Monáe used Mayweather and other spinoff characters as metaphors for her sense of otherness, as a queer Black woman from Kansas City, Kansas. (In 2018, she came out as pansexual, and last April revealed herself to be nonbinary; she uses she/her or they/them pronouns but says that her preferred pronoun is “freeassmuthafucka.”) Monaé’s forty-eight-minute

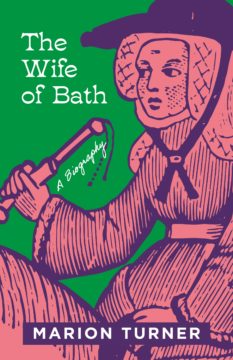

So who is Janelle Monáe? Since she emerged on the music scene, she’s been less a pop star than a world-builder, refracting herself through sci-fi and Afrofuturist imagery. Her first EP, “Metropolis: The Chase Suite,” from 2007, drew on Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist classic and cast Monáe as her android alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. With her tuxedos and protruding pompadours, she was a glam retro-futurist androgyne, and her three studio albums—“The ArchAndroid” (2010), “The Electric Lady” (2013), and “Dirty Computer” (2018)—leaned into her funk-robot persona. “I’m a cyber-girl without a face, a heart, or a mind,” she sang on one track. Monáe used Mayweather and other spinoff characters as metaphors for her sense of otherness, as a queer Black woman from Kansas City, Kansas. (In 2018, she came out as pansexual, and last April revealed herself to be nonbinary; she uses she/her or they/them pronouns but says that her preferred pronoun is “freeassmuthafucka.”) Monaé’s forty-eight-minute  How does an Oxford academic follow up a prize-winning trade book, a newly researched biography of Geoffrey Chaucer? And, moreover, in lockdown, when archives and libraries are largely inaccessible? Marion Turner, the newly elected J R R Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language at Oxford, has avoided ‘second-book syndrome’ with a breathtakingly simple idea: a biography of Chaucer’s most famous character, Dame Alison (or Alice), weaver, pilgrim, businesswoman and serial participant in the marriage market, better known as the Wife of Bath. Informative, clear-sighted, entertaining and as opinionated as its subject, Turner’s new book is a wonderful introduction to the lives of 14th-century women, The Canterbury Tales and the fascinating ways in which Alison has been read and misread since she first hoisted up her voluminous skirts to show her fine red stockings during the last decade of the 14th century.

How does an Oxford academic follow up a prize-winning trade book, a newly researched biography of Geoffrey Chaucer? And, moreover, in lockdown, when archives and libraries are largely inaccessible? Marion Turner, the newly elected J R R Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language at Oxford, has avoided ‘second-book syndrome’ with a breathtakingly simple idea: a biography of Chaucer’s most famous character, Dame Alison (or Alice), weaver, pilgrim, businesswoman and serial participant in the marriage market, better known as the Wife of Bath. Informative, clear-sighted, entertaining and as opinionated as its subject, Turner’s new book is a wonderful introduction to the lives of 14th-century women, The Canterbury Tales and the fascinating ways in which Alison has been read and misread since she first hoisted up her voluminous skirts to show her fine red stockings during the last decade of the 14th century. Something was in the water in Austin. In the 1960s, a gang of classics scholars and philosophy professors had rolled into town like bandits, the University of Texas their saloon: William Arrowsmith, chair of the Classics Department, who scandalized the academic humanities with a Harper’s Magazine essay titled “The Shame of the Graduate Schools,” arguing that “the humanists have betrayed the humanities” and that “an alarmingly high proportion of what is published in classics—and in other fields—is simply rubbish or trivia”; John Silber, promoted to dean of the College of Arts and Sciences just ten years after graduating from Yale, who promptly replaced twenty-two department heads, much to the ire of the university’s board; and a third, an unassuming former radio broadcaster from the United Kingdom with a knack for classical languages and only a master’s degree to his name.

Something was in the water in Austin. In the 1960s, a gang of classics scholars and philosophy professors had rolled into town like bandits, the University of Texas their saloon: William Arrowsmith, chair of the Classics Department, who scandalized the academic humanities with a Harper’s Magazine essay titled “The Shame of the Graduate Schools,” arguing that “the humanists have betrayed the humanities” and that “an alarmingly high proportion of what is published in classics—and in other fields—is simply rubbish or trivia”; John Silber, promoted to dean of the College of Arts and Sciences just ten years after graduating from Yale, who promptly replaced twenty-two department heads, much to the ire of the university’s board; and a third, an unassuming former radio broadcaster from the United Kingdom with a knack for classical languages and only a master’s degree to his name. H

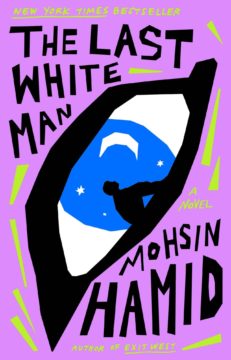

H The anonymous setting of Mohsin Hamid’s 2022 novel The Last White Man brings with it a certain comfort. The British Pakistani author’s lack of specificity is purposeful: dropped into a nameless town in an unknown country, the reader has no cultural touchstones to grab onto, no societal baggage to carry. The blank slate leaves just one aspect to focus on, which Hamid homes in on with his first line: “One morning Anders, a white man, woke up to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown.” This succinct statement of fact — a rarity in the novel — establishes the binary law of the land: you’re either white or dark, no in-between.

The anonymous setting of Mohsin Hamid’s 2022 novel The Last White Man brings with it a certain comfort. The British Pakistani author’s lack of specificity is purposeful: dropped into a nameless town in an unknown country, the reader has no cultural touchstones to grab onto, no societal baggage to carry. The blank slate leaves just one aspect to focus on, which Hamid homes in on with his first line: “One morning Anders, a white man, woke up to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown.” This succinct statement of fact — a rarity in the novel — establishes the binary law of the land: you’re either white or dark, no in-between. When clinical trial data for the antiviral drug Paxlovid emerged in late 2021, physicians hailed its astonishing efficacy — a reduction of nearly 90% in the risk of severe COVID-19. But more than a year later, COVID-19 remains a leading cause of death in many countries, and not only in

When clinical trial data for the antiviral drug Paxlovid emerged in late 2021, physicians hailed its astonishing efficacy — a reduction of nearly 90% in the risk of severe COVID-19. But more than a year later, COVID-19 remains a leading cause of death in many countries, and not only in  During the three decades that I headed Human Rights Watch, I recognized that we would never attract donors who wanted to exempt their favorite country from the objective application of international human rights principles. That is the price of respecting principles.

During the three decades that I headed Human Rights Watch, I recognized that we would never attract donors who wanted to exempt their favorite country from the objective application of international human rights principles. That is the price of respecting principles. ILLUSION AND REALITY

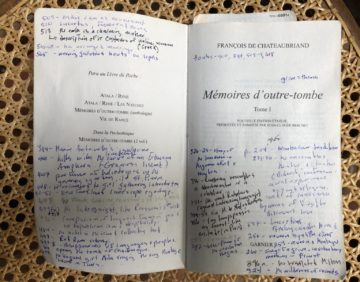

ILLUSION AND REALITY Chateaubriand says that the pleasures of youth revisited in memory are ruins seen by torchlight. I don’t know whether I’m the ruin or the torch.

Chateaubriand says that the pleasures of youth revisited in memory are ruins seen by torchlight. I don’t know whether I’m the ruin or the torch.