Michael Shellenberger in his Substack newsletter:

On CBS “60 Minutes” last night, scientists claimed that humans are causing a “sixth mass extinction” and that we would need the equivalent of five planet earths for all humans to live at current Western levels.

On CBS “60 Minutes” last night, scientists claimed that humans are causing a “sixth mass extinction” and that we would need the equivalent of five planet earths for all humans to live at current Western levels.

“No, humanity is not sustainable to maintain our lifestyle — yours and mine,” claimed Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich. “Basically, for the entire planet, you’d need five more Earths. It’s not clear where they’re gonna come from.”

Both claims are wrong and have been repeatedly debunked in the peer-reviewed scientific literature.

The assertion that “five more Earths” are needed to sustain humanity comes from something called the Ecological Footprint calculation. I debunked it 10 years ago with a group of other analysts and scientists, including the Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy, in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, PLOS Biology.

More here.

China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “

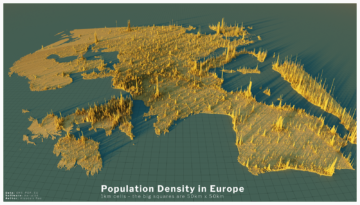

China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “ It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of

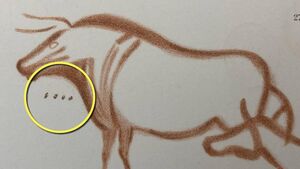

It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of  A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings.

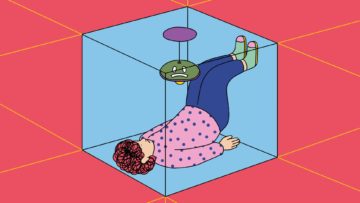

A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings. You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.”

You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.” Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at

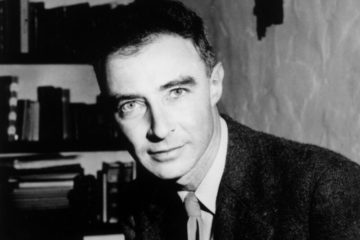

Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at  Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist  Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too.

Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too. The village was located in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, on the edge of the dense Hasdeo Arand forest. One of India’s few pristine and contiguous tracts of forest, Hasdeo Arand sprawls across more than 1,500 sq km. The land is home to rare plants such as epiphytic orchids and smilax, endangered animals such as sloth bears and elephants, and sal trees so tall they seem to brush against the sky.

The village was located in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, on the edge of the dense Hasdeo Arand forest. One of India’s few pristine and contiguous tracts of forest, Hasdeo Arand sprawls across more than 1,500 sq km. The land is home to rare plants such as epiphytic orchids and smilax, endangered animals such as sloth bears and elephants, and sal trees so tall they seem to brush against the sky. The hotel ballroom was packed to near capacity with scientists when Susan Yanovski arrived. Despite being 10 minutes early, she had to manoeuvre her way to one of the few empty seats near the back. The audience at the ObesityWeek conference in San Diego, California, in November 2022, was waiting to hear the results of a hotly anticipated drug trial. The presenters — researchers affiliated with pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, based in Bagsværd, Denmark — did not disappoint. They described the details of an investigation of a promising anti-obesity medication in teenagers, a group that is notoriously resistant to such treatment. The results astonished researchers: a weekly injection for almost 16 months, along with some lifestyle changes, reduced body weight by at least 20% in more than one-third of the participants

The hotel ballroom was packed to near capacity with scientists when Susan Yanovski arrived. Despite being 10 minutes early, she had to manoeuvre her way to one of the few empty seats near the back. The audience at the ObesityWeek conference in San Diego, California, in November 2022, was waiting to hear the results of a hotly anticipated drug trial. The presenters — researchers affiliated with pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, based in Bagsværd, Denmark — did not disappoint. They described the details of an investigation of a promising anti-obesity medication in teenagers, a group that is notoriously resistant to such treatment. The results astonished researchers: a weekly injection for almost 16 months, along with some lifestyle changes, reduced body weight by at least 20% in more than one-third of the participants C

C Brann’s new book sweeps across the vast range of things that hold her interest. It thus invites us to enjoy the life of the mind and to live from our highest selves. A thoughtful encounter with this book will make you, I swear, a better person. The book includes chapters on Thing-Love, the Aztecs, Athens, Jane Austen, Plato, Wisdom, the Idea of the Good. The first half provides an on-ramp to the chapter titled “On Being Interested,” which falls in the dead center of the book. This central chapter serves as more than a cog in the wheel: it is an ars poetica. Addressing issues of attention, focus, and interest itself, as well as how and where to deploy these functions throughout our lives, “Being Interested” offers a solution for any seeker intrigued by the notion that happiness is not an accident but a vocation. Brann characterizes the pursuit of happiness as “ontological optimism […] to be maintained in the face of reality’s recalcitrance.” In her 2010 book Homage to Americans: Mile-High Meditations, Close Readings, and Time-Spanning Speculations, Brann recounts her experience of waiting for a delayed flight at the Denver Airport. Rather than whining about the tedium and soul-sucking banality of the event, she turns her exquisite attention to the actual experience of “waiting.” Possessed of a consistent ability to enjoy, Brann seems literally incapable of boredom.

Brann’s new book sweeps across the vast range of things that hold her interest. It thus invites us to enjoy the life of the mind and to live from our highest selves. A thoughtful encounter with this book will make you, I swear, a better person. The book includes chapters on Thing-Love, the Aztecs, Athens, Jane Austen, Plato, Wisdom, the Idea of the Good. The first half provides an on-ramp to the chapter titled “On Being Interested,” which falls in the dead center of the book. This central chapter serves as more than a cog in the wheel: it is an ars poetica. Addressing issues of attention, focus, and interest itself, as well as how and where to deploy these functions throughout our lives, “Being Interested” offers a solution for any seeker intrigued by the notion that happiness is not an accident but a vocation. Brann characterizes the pursuit of happiness as “ontological optimism […] to be maintained in the face of reality’s recalcitrance.” In her 2010 book Homage to Americans: Mile-High Meditations, Close Readings, and Time-Spanning Speculations, Brann recounts her experience of waiting for a delayed flight at the Denver Airport. Rather than whining about the tedium and soul-sucking banality of the event, she turns her exquisite attention to the actual experience of “waiting.” Possessed of a consistent ability to enjoy, Brann seems literally incapable of boredom.

IFC Films has released a

IFC Films has released a