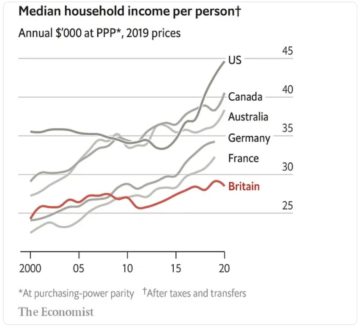

Adam Tooze in Chartbook:

After a year of political turmoil and financial embarrassment, Britain ends 2022 shaken. There is a new spate of talk about national decline. Once again the UK is falling behind. The outlook is uncertain. It is symptomatic that Perry Anderson chose already in 2020, to author yet another gigantic essay for the New Left Review on the UK.

After a year of political turmoil and financial embarrassment, Britain ends 2022 shaken. There is a new spate of talk about national decline. Once again the UK is falling behind. The outlook is uncertain. It is symptomatic that Perry Anderson chose already in 2020, to author yet another gigantic essay for the New Left Review on the UK.

I generally avoid writing about the UK. My feeling about the country are too conflicted. But the discussion going on right now makes it irresistible. It seems as though half a century or more of debate are once again up for grabs.

Though the British elite had a first attack of nerves around 1900 as imperialist rivals emerged on the scene, the decline debate as we know it today originated in the 1950s, within the frame of US hegemony, at a moment when imperial humiliation in Suez coincided, as Jim Tomlinson has shown with the publication of new comparative productivity figures by the OECD.

More here.

Though never a household name, Bruce Duffy drew rapturous critical praise for his 1987 debut novel,

Though never a household name, Bruce Duffy drew rapturous critical praise for his 1987 debut novel,  This past spring, the philosopher Richard J. Bernstein taught his final two classes at the New School for Social Research, in New York, where he had been a professor since 1989. One was a course on American pragmatism, the tradition to which his own work belongs. The other was a seminar on

This past spring, the philosopher Richard J. Bernstein taught his final two classes at the New School for Social Research, in New York, where he had been a professor since 1989. One was a course on American pragmatism, the tradition to which his own work belongs. The other was a seminar on  I

I I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity.

I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity. SOMETIME THIS COMING

SOMETIME THIS COMING One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness.

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness. Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

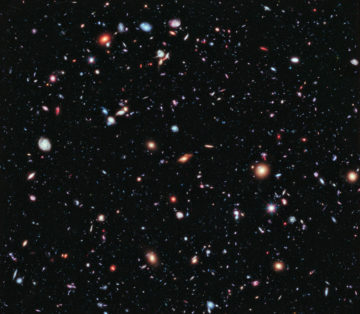

Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior.

To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior. Each of us constructs and lives a “narrative”,’ wrote the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, ‘this narrative is us’. Likewise the American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner: ‘Self is a perpetually rewritten story.’ And: ‘In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we “tell about” our lives.’ Or a fellow American psychologist, Dan P McAdams: ‘We are all storytellers, and we are the stories we tell.’ And here’s the American moral philosopher J David Velleman: ‘We invent ourselves… but we really are the characters we invent.’ And, for good measure, another American philosopher, Daniel Dennett: ‘we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behaviour… and we always put the best “faces” on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography. The chief fictional character at the centre of that autobiography is one’s self.’

Each of us constructs and lives a “narrative”,’ wrote the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, ‘this narrative is us’. Likewise the American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner: ‘Self is a perpetually rewritten story.’ And: ‘In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we “tell about” our lives.’ Or a fellow American psychologist, Dan P McAdams: ‘We are all storytellers, and we are the stories we tell.’ And here’s the American moral philosopher J David Velleman: ‘We invent ourselves… but we really are the characters we invent.’ And, for good measure, another American philosopher, Daniel Dennett: ‘we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behaviour… and we always put the best “faces” on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography. The chief fictional character at the centre of that autobiography is one’s self.’ What do Noam Chomsky, living legend of linguistics, Kai-Fu Lee, perhaps the most famous AI researcher in all of China, and Yejin Choi, the 2022 MacArthur Fellowship winner who was profiled earlier this week in The New York Times Magazine—and more than a dozen other scientists, economists, researchers, and elected officials—all have in common?

What do Noam Chomsky, living legend of linguistics, Kai-Fu Lee, perhaps the most famous AI researcher in all of China, and Yejin Choi, the 2022 MacArthur Fellowship winner who was profiled earlier this week in The New York Times Magazine—and more than a dozen other scientists, economists, researchers, and elected officials—all have in common?