Emily Temple in Lit Hub:

For years, I resisted Mrs. Bridge. I remember picking up the 50th-anniversary edition from a display of staff picks at McNally-Jackson; someone had just been gushing to me about how great it was, and at least one staff member seemed to agree: the suggestion card was crammed with cramped praise. But I was turned off by the cover, which seemed altogether too misty and domestic, an impression that the description did nothing to disabuse: this was a Classic American Novel, a slice-of-life “family story” about a wealthy woman living in Kansas City between the First and Second World Wars. It was the 1959 debut novel of a writer I’d never heard of otherwise, a white guy named Evan S. Connell. Meh, I thought.

For years, I resisted Mrs. Bridge. I remember picking up the 50th-anniversary edition from a display of staff picks at McNally-Jackson; someone had just been gushing to me about how great it was, and at least one staff member seemed to agree: the suggestion card was crammed with cramped praise. But I was turned off by the cover, which seemed altogether too misty and domestic, an impression that the description did nothing to disabuse: this was a Classic American Novel, a slice-of-life “family story” about a wealthy woman living in Kansas City between the First and Second World Wars. It was the 1959 debut novel of a writer I’d never heard of otherwise, a white guy named Evan S. Connell. Meh, I thought.

I finally read it for the first time this year, after what must have been the hundredth recommendation from someone I trusted. It only took me about ten pages to realize what an idiot I had been. Meh, indeed. This novel is glorious.

But even as I read, enthralled, once and then a second time, I couldn’t quite figure out why. There’s no obvious reason Mrs. Bridge should be so good, especially if like me, you’re officially bored by the broad thematic strokes outlined above.

More here.

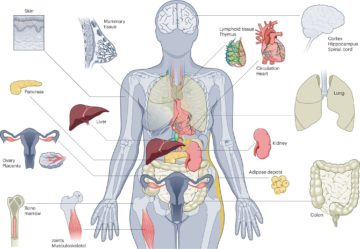

Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality.

Multiple researchers at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) are taking part in an ambitious research program spanning several top research institutions to study senescent cells. Senescent cells stop dividing in response to stressors and seemingly have a role to play in human health and the aging process. Recent research with mice suggests that clearing senescent cells delays the onset of age-related dysfunction and disease as well as all-cause mortality. E

E In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you.

In a quiet group chat in an obscure part of the internet, a small number of anonymous accounts are swapping references from academic publications and feverishly poring over complex graphs of DNA analysis. These are not your average trolls, but scholars, researchers and students who have come together online to discuss the latest findings in archaeology. Why would established academics not be having these conversations in a conference hall or a lecture theatre? The answer might surprise you. I work on AI alignment,

I work on AI alignment,  That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret.

That we often are not the masters of our own machines, and can even become their witless lackeys, is a cautionary claim as old as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and as urgent as the latest bogus newsfeed on Dr. Fauci’s evil ways. (Instead of saving lives, he’s been busy, don’t you know, torturing puppies, rendering impotent our patriotic men, and implanting surveillance chips in our brains: accusations all conveyed via apps relentlessly surveilled by Facebook, Apple, Google, and their like.) As a species gifted with inventive minds and opposable thumbs, we are ever about the business of generating new tools and techniques that will, we are certain, better our lives. Time after time, though, those new methods and machines also prove to change our public spaces and private selves in radical ways we fail to foresee and come to regret. IN A TEACHING MANUAL she wrote in the 1980s, the artist Sybil Andrews stressed the importance of reaching into an image for its essence, stripping away whatever stagnated it. “Can you catch that? Can you get that sense of movement?” she would ask. The advice revealed a design philosophy that had defined her work for decades: her 1931 linocut In Full Cry shows a row of horses leaping over a hedge, their riders’ coattails soaring behind them. The lines themselves are Andrews’s subject, vigorous and unflinching. “I don’t draw the horse jumping,” she said. “I draw the jump.”

IN A TEACHING MANUAL she wrote in the 1980s, the artist Sybil Andrews stressed the importance of reaching into an image for its essence, stripping away whatever stagnated it. “Can you catch that? Can you get that sense of movement?” she would ask. The advice revealed a design philosophy that had defined her work for decades: her 1931 linocut In Full Cry shows a row of horses leaping over a hedge, their riders’ coattails soaring behind them. The lines themselves are Andrews’s subject, vigorous and unflinching. “I don’t draw the horse jumping,” she said. “I draw the jump.” To write a letter or a postcard meant, relatively speaking, going slow. This was particularly so if one wrote by hand, but true too with a typewriter or word processor and printer. People have always liked to complain about the speed of the mail, but today the once-noble medium has been denigrated to the point of being deemed “snail mail.” Contracts to carry the mail once were prestigious and coveted things and underwrote our evolving national transportation system. The concept of a “post road” dates to colonial times. The Old Boston Post Road, which began as a forest trail in 1673 and eventually became part of US Route 1, is a common reference still in the vernacular of southern New England. Waterways, filling up with mail-carrying canal boats and paddlewheel steamers, were declared post roads in 1823. The Pony Express, though it operated only for eighteen months in 1860 and 1861, quickly entered the mythology of the Old West.

To write a letter or a postcard meant, relatively speaking, going slow. This was particularly so if one wrote by hand, but true too with a typewriter or word processor and printer. People have always liked to complain about the speed of the mail, but today the once-noble medium has been denigrated to the point of being deemed “snail mail.” Contracts to carry the mail once were prestigious and coveted things and underwrote our evolving national transportation system. The concept of a “post road” dates to colonial times. The Old Boston Post Road, which began as a forest trail in 1673 and eventually became part of US Route 1, is a common reference still in the vernacular of southern New England. Waterways, filling up with mail-carrying canal boats and paddlewheel steamers, were declared post roads in 1823. The Pony Express, though it operated only for eighteen months in 1860 and 1861, quickly entered the mythology of the Old West. Before it was an edict, and a death sentence, it was a rumor. To many, it must have seemed improbable; I imagine my grandmother, buying her vegetables at the market, settling her baby on her hip, craning to hear the news—a border, where? Two borders, to be exact. On the eve of their departure, in 1947, after more than three hundred years on the subcontinent, the British sliced the land into a Hindu-majority India flanked by a Muslim-majority West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), a thousand miles apart. The boundaries were drawn up in five weeks by an English barrister who had famously never before been east of Paris; he flew home directly afterward and burned his papers. The slash of his pen is known as Partition.

Before it was an edict, and a death sentence, it was a rumor. To many, it must have seemed improbable; I imagine my grandmother, buying her vegetables at the market, settling her baby on her hip, craning to hear the news—a border, where? Two borders, to be exact. On the eve of their departure, in 1947, after more than three hundred years on the subcontinent, the British sliced the land into a Hindu-majority India flanked by a Muslim-majority West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), a thousand miles apart. The boundaries were drawn up in five weeks by an English barrister who had famously never before been east of Paris; he flew home directly afterward and burned his papers. The slash of his pen is known as Partition. In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realisation of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realisation of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’ Females, on average, are better than males at putting themselves in others’ shoes and imagining what the other person is thinking or feeling, suggests a new study of over 300,000 people in 57 countries.

Females, on average, are better than males at putting themselves in others’ shoes and imagining what the other person is thinking or feeling, suggests a new study of over 300,000 people in 57 countries. The U.S. use of nuclear weapons against Japan during World War II has long been a subject of emotional debate. Initially, few questioned President Truman’s decision to drop two atomic bombs, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But, in 1965, historian Gar Alperovitz argued that, although the bombs did force an immediate end to the war, Japan’s leaders had wanted to surrender anyway and likely would have done so before the American invasion planned for Nov. 1. Their use was, therefore, unnecessary. Obviously, if the bombings weren’t necessary to win the war, then bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong. In the 48 years since, many others have joined the fray: some echoing Alperovitz and denouncing the bombings, others rejoining hotly that the bombings were moral, necessary, and life-saving.

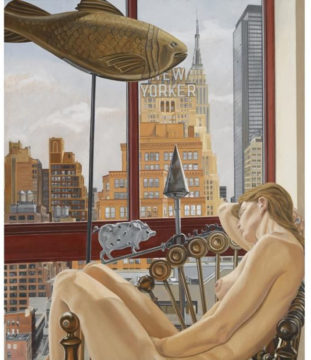

The U.S. use of nuclear weapons against Japan during World War II has long been a subject of emotional debate. Initially, few questioned President Truman’s decision to drop two atomic bombs, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But, in 1965, historian Gar Alperovitz argued that, although the bombs did force an immediate end to the war, Japan’s leaders had wanted to surrender anyway and likely would have done so before the American invasion planned for Nov. 1. Their use was, therefore, unnecessary. Obviously, if the bombings weren’t necessary to win the war, then bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong. In the 48 years since, many others have joined the fray: some echoing Alperovitz and denouncing the bombings, others rejoining hotly that the bombings were moral, necessary, and life-saving. FROM THE OUTSET, Pearlstein has occupied an anomalous position within his generation, for he has been not only the most uncompromising exponent of an unpopular style but its most visible and possibly most successful practitioner. In large measure, Pearlstein owes his special status among fellow Realists and within the art world generally to his gift for ideas and advocacy. It was more by force of argument than by example that he was able in the early 1960s to place a supposedly marginal concern—painting the figure from life—somewhere near the center of critical debate, and to link his cause to that of other artists, many of them abstractionists, who were faced with the task of sorting out the debris left by the first wave of Abstract Expressionism.

FROM THE OUTSET, Pearlstein has occupied an anomalous position within his generation, for he has been not only the most uncompromising exponent of an unpopular style but its most visible and possibly most successful practitioner. In large measure, Pearlstein owes his special status among fellow Realists and within the art world generally to his gift for ideas and advocacy. It was more by force of argument than by example that he was able in the early 1960s to place a supposedly marginal concern—painting the figure from life—somewhere near the center of critical debate, and to link his cause to that of other artists, many of them abstractionists, who were faced with the task of sorting out the debris left by the first wave of Abstract Expressionism. A FEW YEARS AGO, while flipping through the new arrivals crate at Nice Price Records in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was visiting family over the holidays, I became transfixed by what I heard playing on the store’s stereo system. It was immediately recognizable as Christmas music: A jubilant, resonant male baritone implored the listener to “let me hang my mistletoe over your head / and let me love you.” But the voice, landing somewhere between the velvet burliness of Teddy Pendergrass and the genteel phrasing of Lou Rawls, like the lustrous production and extravagant, modern R&B arrangement, which included female backup singers who swooned along to the singer’s seductive caroling, seemed unlocatable. Likewise, the song, a lurching minor-key slow jam in 3/4 time, had a weird melancholia at odds with the enforced buoyancy of the holiday season even as it summoned a long tradition of holiday music, such as “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” and “Blue Christmas,” that expresses how cheery expectations at year’s end can often yield an aching emptiness. Amid these mixed messages and sundry stylistic signals, it was hard to tell if the song was festive burlesque or heartfelt holiday paean. I was intrigued, to say the least.

A FEW YEARS AGO, while flipping through the new arrivals crate at Nice Price Records in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was visiting family over the holidays, I became transfixed by what I heard playing on the store’s stereo system. It was immediately recognizable as Christmas music: A jubilant, resonant male baritone implored the listener to “let me hang my mistletoe over your head / and let me love you.” But the voice, landing somewhere between the velvet burliness of Teddy Pendergrass and the genteel phrasing of Lou Rawls, like the lustrous production and extravagant, modern R&B arrangement, which included female backup singers who swooned along to the singer’s seductive caroling, seemed unlocatable. Likewise, the song, a lurching minor-key slow jam in 3/4 time, had a weird melancholia at odds with the enforced buoyancy of the holiday season even as it summoned a long tradition of holiday music, such as “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” and “Blue Christmas,” that expresses how cheery expectations at year’s end can often yield an aching emptiness. Amid these mixed messages and sundry stylistic signals, it was hard to tell if the song was festive burlesque or heartfelt holiday paean. I was intrigued, to say the least.