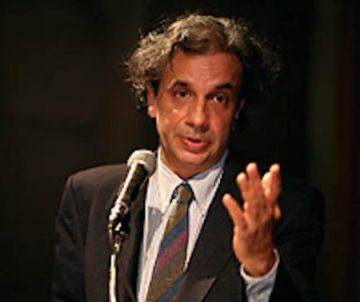

Akeel Bilgrami (along with many others) in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

February 14, 1989, and September 11, 2001, have stood like bookends in my occasional writing on contemporary politics as it relates to Muslims. A rite of passage, a personal education. But the personal here reflects something wider in American, more generally Western, public life.

February 14, 1989, and September 11, 2001, have stood like bookends in my occasional writing on contemporary politics as it relates to Muslims. A rite of passage, a personal education. But the personal here reflects something wider in American, more generally Western, public life.

When the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was pronounced on the first of those dates, I had written critically of the absolutist stances taken by some Muslims in the aftermath of the publication of The Satanic Verses and in support of the commitments to free expression that I had been accustomed to in all the societies (India, England, America) I had inhabited. The long aftermath of the atrocities on September 11 found me withdrawing from these critical undertakings — not out of any funk but, curiously, out of a sense that it was the only self-respecting thing to do. My reason was just this: one does not make criticisms on demand. And there was an expectation, occasionally even explicitly voiced to me, that a Muslim living in a society that had been subjected to such an atrocity, should be declaring his anti-Jihadi credentials. It soon became clear, in fact, that criticism of extremist Islamist politics had become a sort of career path for Muslims in this part of the world and it was not a path I was willing to tread, even though a certain recognizably zealous type — some among my friends — thought my reaction to be too rarefied in its scruple.

This raises a wide range of issues about truth, speech, and location.

More here.