Love is a Luminous Insect at the Window

—for Lauren Marie Espada

The word love: there it is again. Indestructible as an insect,

fly faster than a swatter, mosquito darting through a net.

How the word love chirps in every song, crickets keeping

a city boy up all night. I wish I could fry and eat them.

How the word love buzzes in sonnet after sonnet. I am

the beekeeper who awakes from a nightmare of beehives.

To quote Durán, The Panamanian brawler who waved a glove

and walked away in the middle of fight: No más. No more.

Then I see you, watching the violinist, his eyes shut, the Russian

composer’s concerto in his head, white horsehair fraying on the bow,

and your face is bright with tears, and there it is again, the word love,

not a fly or a mosquito, not a cricket or a bee, but the Luna moth

we saw one night, luminous green wings knocking at the screen

on the window as if to say I have a week to live, let me in, and I do.

by Martín Espada

from Floaters

W.W. Norton, 2021

B

B IN THE FEW TIMES

IN THE FEW TIMES Early on in “Sea Oak,” a short story from Pastoralia, the second of five collections by George Saunders, the characters watch a TV show called How My Child Died Violently. The show is hosted by “a six-foot-five blond,” Saunders writes, “who’s always giving the parents shoulder rubs and telling them they’ve been sainted by pain.” The episode they’re watching features a 10-year-old who killed a 5-year-old for refusing to join his gang.

Early on in “Sea Oak,” a short story from Pastoralia, the second of five collections by George Saunders, the characters watch a TV show called How My Child Died Violently. The show is hosted by “a six-foot-five blond,” Saunders writes, “who’s always giving the parents shoulder rubs and telling them they’ve been sainted by pain.” The episode they’re watching features a 10-year-old who killed a 5-year-old for refusing to join his gang. Even if it uses a fantastically complicated machine playing games with image combinations, any model is only the sum of what it is trained on. In the case of DALL·E 2, the model is trained on a comprehensive corpus of humanity’s collected visual output. Some hopeful proponents call it a kind of imaginative mirror: something that can reflect our own mental image back to us. We could think about our own visual imaginations in terms of models, too. They are trained on some smaller and less complete set of humankind’s vision. There is a potential gap, though, between our imagination and the computer’s “dreams about electric sheep.” Can this model cross that gap?

Even if it uses a fantastically complicated machine playing games with image combinations, any model is only the sum of what it is trained on. In the case of DALL·E 2, the model is trained on a comprehensive corpus of humanity’s collected visual output. Some hopeful proponents call it a kind of imaginative mirror: something that can reflect our own mental image back to us. We could think about our own visual imaginations in terms of models, too. They are trained on some smaller and less complete set of humankind’s vision. There is a potential gap, though, between our imagination and the computer’s “dreams about electric sheep.” Can this model cross that gap? Maize is arguably the single most important crop in the world and is rivalled only by soybeans in terms of versatility. That said, it is, along with sugar cane and palm oil, among the most controversial crops, proving particularly so to critics of industrial agriculture. Although maize is usually associated with the Western world, it has played a prominent role in Asia for a long time, and, in recent decades, its importance in Asia has soared. For better or worse, or more likely for better and worse, its role in Asia seems to be following the Western script.

Maize is arguably the single most important crop in the world and is rivalled only by soybeans in terms of versatility. That said, it is, along with sugar cane and palm oil, among the most controversial crops, proving particularly so to critics of industrial agriculture. Although maize is usually associated with the Western world, it has played a prominent role in Asia for a long time, and, in recent decades, its importance in Asia has soared. For better or worse, or more likely for better and worse, its role in Asia seems to be following the Western script. New medicines need not be tested in animals to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, according to legislation signed by President Joe Biden in late December 2022. The change—long sought by animal welfare organizations—could signal a major shift away from animal use after more than 80 years of drug safety regulation.

New medicines need not be tested in animals to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, according to legislation signed by President Joe Biden in late December 2022. The change—long sought by animal welfare organizations—could signal a major shift away from animal use after more than 80 years of drug safety regulation. The next revolution in medicine just might come from a new lab technique that makes neurons sensitive to light. The technique, called

The next revolution in medicine just might come from a new lab technique that makes neurons sensitive to light. The technique, called  This story is a love story, though its main character is not a person but a thing. The telephone, in this story, determines the possible and the impossible. Back in the 1990s, there were two telephones in my house in Karachi. The downstairs phone was a pale gray rotary model, which was placed on an end table in our formal sitting room. A phone call was still an occasion for the elders in our house, especially for my grandparents, who had known life without it. Each call cost money, and since every expenditure was closely monitored in our home, so, too, was the use of the telephone. When you did make a call, you would sit on the edge of the armchair, so as not to create an imprint or a sweat stain on the good furniture, and carefully dial each digit. Anyone walking by the glass door of the sitting room was entitled to ask who was on the other end of the line. Unlike now, one phone belonged to a whole household. Unlike now, it had to be shared.

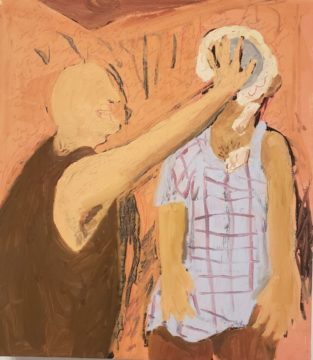

This story is a love story, though its main character is not a person but a thing. The telephone, in this story, determines the possible and the impossible. Back in the 1990s, there were two telephones in my house in Karachi. The downstairs phone was a pale gray rotary model, which was placed on an end table in our formal sitting room. A phone call was still an occasion for the elders in our house, especially for my grandparents, who had known life without it. Each call cost money, and since every expenditure was closely monitored in our home, so, too, was the use of the telephone. When you did make a call, you would sit on the edge of the armchair, so as not to create an imprint or a sweat stain on the good furniture, and carefully dial each digit. Anyone walking by the glass door of the sitting room was entitled to ask who was on the other end of the line. Unlike now, one phone belonged to a whole household. Unlike now, it had to be shared. For the first eight years of her life as an artist, Tala Madani, who was born in Tehran, painted only men, and not to their credit. “Caked,” in 2005, shows a brawny, nearly featureless oaf in a black undershirt smashing a cake in another oaf’s face. Next came a series of small paintings of men with plants growing out of their crotch—one of them tends to his foliage with a watering can. In 2011, she painted several men whose testicles hung from their chin, and a man in spirited conversation with his vital organs, which have been removed and placed in a comfortable chair. A series of 2015 paintings present men whose colossal, fire-hose penises take on lives of their own. None of these images suggest animosity toward the male species. The harmless dopes in Madani’s early work gave way to middle-aged, potbellied, bearded losers, whose weird plights make us laugh. Madani is that rarity in art, a wildly imaginative innovator with a gift for caricature and visual satire, and her first great subject was the absurdity of machismo. “I do think machismo is healthy and alive everywhere, and I was having fun upending it,” she told me last summer, when we began a number of conversations. “You know, you want it to grow bigger, so why not water it?”

For the first eight years of her life as an artist, Tala Madani, who was born in Tehran, painted only men, and not to their credit. “Caked,” in 2005, shows a brawny, nearly featureless oaf in a black undershirt smashing a cake in another oaf’s face. Next came a series of small paintings of men with plants growing out of their crotch—one of them tends to his foliage with a watering can. In 2011, she painted several men whose testicles hung from their chin, and a man in spirited conversation with his vital organs, which have been removed and placed in a comfortable chair. A series of 2015 paintings present men whose colossal, fire-hose penises take on lives of their own. None of these images suggest animosity toward the male species. The harmless dopes in Madani’s early work gave way to middle-aged, potbellied, bearded losers, whose weird plights make us laugh. Madani is that rarity in art, a wildly imaginative innovator with a gift for caricature and visual satire, and her first great subject was the absurdity of machismo. “I do think machismo is healthy and alive everywhere, and I was having fun upending it,” she told me last summer, when we began a number of conversations. “You know, you want it to grow bigger, so why not water it?” Here’s an example of “covert arrogance,” from Jersey Breaks: when I was twenty years old, I applied to a foundation for money I was hoping to live on for the year after I graduated from college.

Here’s an example of “covert arrogance,” from Jersey Breaks: when I was twenty years old, I applied to a foundation for money I was hoping to live on for the year after I graduated from college. If we define consciousness along the lines of Thomas Nagel as the inner feel of existence, the fact that for some beings “there is something it is like to be them”, is it outlandish to believe that Artificial Intelligence, given what it is today, can ever be conscious?

If we define consciousness along the lines of Thomas Nagel as the inner feel of existence, the fact that for some beings “there is something it is like to be them”, is it outlandish to believe that Artificial Intelligence, given what it is today, can ever be conscious? In his new book, The Walls around Opportunity, Gary Orfield—a leading scholar of civil rights in education—shows that what did work was straightforward legal and budgetary coercion. School districts would no longer be able to file desegregation plans and go home with an A for effort. Civil rights lawyers no longer had to sue each segregated school district one at a time; legislation authorized class-action lawsuits and the withholding of federal funds from any entity that failed to produce measurable progress toward desegregation. Perhaps in part because the United States was a nation created, expanded, and maintained through the use of force, it was force, legal and fiscal, that finally got results—at least for a brief historical moment.

In his new book, The Walls around Opportunity, Gary Orfield—a leading scholar of civil rights in education—shows that what did work was straightforward legal and budgetary coercion. School districts would no longer be able to file desegregation plans and go home with an A for effort. Civil rights lawyers no longer had to sue each segregated school district one at a time; legislation authorized class-action lawsuits and the withholding of federal funds from any entity that failed to produce measurable progress toward desegregation. Perhaps in part because the United States was a nation created, expanded, and maintained through the use of force, it was force, legal and fiscal, that finally got results—at least for a brief historical moment. Just after Christmas, the writer Hanif Kureishi was taking a long walk in Rome, where he and his wife, Isabella D’Amico, were spending the holiday, when he suddenly collapsed onto the sidewalk. It is unclear why — perhaps he fainted, said his son Carlo Kureishi, or perhaps he suffered an epileptic fit — but he fell awkwardly, twisting his neck and grievously injuring the top of his spine. When Kureishi regained his senses, he was lying in a pool of blood, unable to move his arms or his legs. “It occurred to me that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body,”

Just after Christmas, the writer Hanif Kureishi was taking a long walk in Rome, where he and his wife, Isabella D’Amico, were spending the holiday, when he suddenly collapsed onto the sidewalk. It is unclear why — perhaps he fainted, said his son Carlo Kureishi, or perhaps he suffered an epileptic fit — but he fell awkwardly, twisting his neck and grievously injuring the top of his spine. When Kureishi regained his senses, he was lying in a pool of blood, unable to move his arms or his legs. “It occurred to me that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body,”