Conor Feehly in Discover:

Human beings — with our big brains, technology and mastery of language — like to describe ourselves as the most intelligent species. After all, we’re capable of reaching space, prolonging our lives and understanding the world around us. Over time, however, our understanding of intelligence has gotten a little more complicated.

Human beings — with our big brains, technology and mastery of language — like to describe ourselves as the most intelligent species. After all, we’re capable of reaching space, prolonging our lives and understanding the world around us. Over time, however, our understanding of intelligence has gotten a little more complicated.

Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein, for example, wielded a logical-mathematical intelligence. But we now recognize that there are other types of intelligence, too: emotional, bodily-kinesthetic, visual-spatial, musical and social, among others that are specific to different human skill sets. Each one of these types enables a person to solve problems relevant to their own situation. And beyond the different varieties of intelligence among humans, scientists are starting to understand the capacity for intelligence in other species — outside of the narrow, human-centric conceptions that have framed our picture of intelligence until now.

More here.

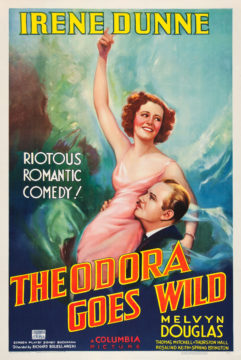

Indeed, Theodora goes wild but never silly, cutting loose but never losing control. And if in her contained exuberance Irene Dunne stands apart from her classic screwball sisters, she is, I think, the actress who best embodies what we truly find most alluring in the genre, what I see as its real beating heart: the way these films’ protagonists break free of the straitened existences they’ve either been trapped in or trapped themselves in (or both). Yes, often with the assistance of a playful playboy, helpfully crazed heiress, alluring cardsharp, or even, sure, Katherine “Sugarpuss” O’Shea, but also, and more important, because they themselves need to and do the work to break free.

Indeed, Theodora goes wild but never silly, cutting loose but never losing control. And if in her contained exuberance Irene Dunne stands apart from her classic screwball sisters, she is, I think, the actress who best embodies what we truly find most alluring in the genre, what I see as its real beating heart: the way these films’ protagonists break free of the straitened existences they’ve either been trapped in or trapped themselves in (or both). Yes, often with the assistance of a playful playboy, helpfully crazed heiress, alluring cardsharp, or even, sure, Katherine “Sugarpuss” O’Shea, but also, and more important, because they themselves need to and do the work to break free. As Bruno Latour confided to Le Monde earlier this year in one of his final interviews,

As Bruno Latour confided to Le Monde earlier this year in one of his final interviews,  First, let’s be clear about what “usage” means. It isn’t grammar, though the two are related and often treated together in such page-turners as

First, let’s be clear about what “usage” means. It isn’t grammar, though the two are related and often treated together in such page-turners as  Health experts are calling for a rethink of Australia’s COVID-19 approach after a new study showed one in 10 people will end up with “long COVID”.

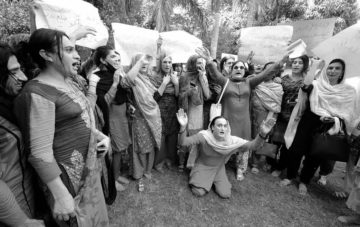

Health experts are calling for a rethink of Australia’s COVID-19 approach after a new study showed one in 10 people will end up with “long COVID”. For centuries, intersex people—those who possess both male and female sexual organs—and those assigned male at birth who have subsequently identified as women have left their homes and joined third-gender communities, where they have been able to express their femininity without fear of persecution. These societies are

For centuries, intersex people—those who possess both male and female sexual organs—and those assigned male at birth who have subsequently identified as women have left their homes and joined third-gender communities, where they have been able to express their femininity without fear of persecution. These societies are  As with weeds in a garden, it is a

As with weeds in a garden, it is a  My stories come to me as clichés. A cliché is a cliché because it’s worthwhile. Otherwise, it would have been discarded. A good cliché can never be overwritten; it’s still mysterious. The concepts of beauty and ugliness are mysterious to me. Many people write about them. In mulling over them, I try to get underneath them and see what they mean, understand the impact they have on what people do. I also write about love and death.

My stories come to me as clichés. A cliché is a cliché because it’s worthwhile. Otherwise, it would have been discarded. A good cliché can never be overwritten; it’s still mysterious. The concepts of beauty and ugliness are mysterious to me. Many people write about them. In mulling over them, I try to get underneath them and see what they mean, understand the impact they have on what people do. I also write about love and death. There are few human impulses more primal than the desire for explanations. We have expectations concerning what happens, and when what we experience differs from those expectations, we want to know the reason why. There are obvious philosophy questions here: What is an explanation? Do explanations bottom out, or go forever? But there are also psychology questions: What precisely is it that we seek when we demand an explanation? What makes us satisfied with one? Tania Lombrozo is a psychologist who is also conversant with the philosophical side of things. She offers some pretty convincing explanations for why we value explanation so highly.

There are few human impulses more primal than the desire for explanations. We have expectations concerning what happens, and when what we experience differs from those expectations, we want to know the reason why. There are obvious philosophy questions here: What is an explanation? Do explanations bottom out, or go forever? But there are also psychology questions: What precisely is it that we seek when we demand an explanation? What makes us satisfied with one? Tania Lombrozo is a psychologist who is also conversant with the philosophical side of things. She offers some pretty convincing explanations for why we value explanation so highly. If the last few years tell us anything, it is that we are well beyond Peak Progress. The decades since the turn of the millennium have seen two international financial crises, terrorist attacks, a return of great-power politics, a brutal and potentially catastrophic war in eastern Europe, a global pandemic, and (at the time of writing) rocketing inflation.

If the last few years tell us anything, it is that we are well beyond Peak Progress. The decades since the turn of the millennium have seen two international financial crises, terrorist attacks, a return of great-power politics, a brutal and potentially catastrophic war in eastern Europe, a global pandemic, and (at the time of writing) rocketing inflation. Unlike other naturalists, who had studied preserved specimens, Jeanne realized that she could only discover the true origin of the shell if she observed living creatures. To bypass the evolution-mounted obstacle of their extreme shyness, she designed and constructed one of the world’s first offshore research stations — a system of immense cages she anchored off the coast of Sicily, complete with observation windows through which she could study the argonauts undisturbed. Every day, she prepared food for them, rowed her boat to the cages in her long skirts, and knelt at the platform, observing for hours on end.

Unlike other naturalists, who had studied preserved specimens, Jeanne realized that she could only discover the true origin of the shell if she observed living creatures. To bypass the evolution-mounted obstacle of their extreme shyness, she designed and constructed one of the world’s first offshore research stations — a system of immense cages she anchored off the coast of Sicily, complete with observation windows through which she could study the argonauts undisturbed. Every day, she prepared food for them, rowed her boat to the cages in her long skirts, and knelt at the platform, observing for hours on end. Carl Stalling’s scores didn’t just teach kids about Beethoven and Mozart and Wagner, they quoted vastly influential songs from his own lifetime that have now vanished down the memory hole, and that inclusion forces conversations about those songs. Parents may differ on whether that’s a good thing, but I think it is. I can avoid Speedy Gonzales, but other forms of bigotry sneak up on me. I don’t relish explaining to my son why he can occasionally catch me absent-mindedly whistling Stephen Foster’s “Shortnin’ Bread” but will never, ever hear me sing the lyrics. If we don’t talk about that, though, I risk letting the attitudes of the past seem incomprehensible and stupid to him, which weakens his resistance to their contemporary descendants. A full appreciation of old cartoons prevents us from reducing their authors to caricature. Stalling loved catchy, racist old minstrel tunes; he’s also single-handedly responsible for the preservation of terrific songs like Raymond Scott’s classic “

Carl Stalling’s scores didn’t just teach kids about Beethoven and Mozart and Wagner, they quoted vastly influential songs from his own lifetime that have now vanished down the memory hole, and that inclusion forces conversations about those songs. Parents may differ on whether that’s a good thing, but I think it is. I can avoid Speedy Gonzales, but other forms of bigotry sneak up on me. I don’t relish explaining to my son why he can occasionally catch me absent-mindedly whistling Stephen Foster’s “Shortnin’ Bread” but will never, ever hear me sing the lyrics. If we don’t talk about that, though, I risk letting the attitudes of the past seem incomprehensible and stupid to him, which weakens his resistance to their contemporary descendants. A full appreciation of old cartoons prevents us from reducing their authors to caricature. Stalling loved catchy, racist old minstrel tunes; he’s also single-handedly responsible for the preservation of terrific songs like Raymond Scott’s classic “ The summer I finished writing my dissertation, the C.I.A. tried to recruit me—as a spy. The call came in the middle of the afternoon, as I was working on a chapter about Tolstoy and midwifery. An older woman with an eerily friendly voice started going over what the training for a job in clandestine affairs would entail. I stifled a laugh. I didn’t know what was harder to believe: that anyone thought I could keep a secret or that a degree in Russian literature would qualify me to parachute out of a plane. Was I interested in learning more? O.K., I said, mostly out of nosiness, or at least that’s what I told myself. They would be in touch, she said.

The summer I finished writing my dissertation, the C.I.A. tried to recruit me—as a spy. The call came in the middle of the afternoon, as I was working on a chapter about Tolstoy and midwifery. An older woman with an eerily friendly voice started going over what the training for a job in clandestine affairs would entail. I stifled a laugh. I didn’t know what was harder to believe: that anyone thought I could keep a secret or that a degree in Russian literature would qualify me to parachute out of a plane. Was I interested in learning more? O.K., I said, mostly out of nosiness, or at least that’s what I told myself. They would be in touch, she said. A rapidly firing laser can divert lightning strikes, scientists have shown for the first time in real-world experiments

A rapidly firing laser can divert lightning strikes, scientists have shown for the first time in real-world experiments