Category: Recommended Reading

Medical Residency

Mabel Powers in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them.

Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them.

The Indians stopped, for the rabbit still sat up before them and did not move from the trail. They shot their arrows at him, but the arrows came back unstained with blood.

A second time they drew their arrows. Now no rabbit was to be seen. Instead an old man stood on the trail. He seemed to be weak and sick.

The old man asked them for food and a place to rest. They would not listen but went on to the settlement.

Slowly the old man followed them, down the trail to the wigwam village. In front of each wigwam, he saw a skin placed on a pole. This he knew was the sign of the clan to which the dwellers in that wigwam belonged.

First he stopped at a wigwam where a wolfskin hung. He asked to enter, but they would not let him. They said, “We want no sick men here.”

On he went toward another wigwam. Here a turtle’s shell was hanging. But this family would not let him in.

He tried a wigwam where he saw a beaver skin. He was told to move on.

More here.

Where is Physics Headed (and How Soon Do We Get There)?

Dennis Overbye in The New York Times:

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

And so this past June, the physics community began to consider what they want to do next, and why.

That is the mandate of a committee appointed by the National Academy of Sciences, called Elementary Particle Physics: Progress and Promise. Sharing the chairmanship are two prominent scientists: Maria Spiropulu, Shang-Yi Ch’en Professor of Physics at the California Institute of Technology, and the cosmologist Michael Turner, an emeritus professor at the University of Chicago, the former assistant director of the National Science Foundation and former president of the American Physical Society.

More here.

Waldemar Tours The World’s Greatest Sculptures

Edna Ferber Revisited

Kathleen Rooney at JSTOR Daily:

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When novelist Joseph Conrad encountered her on a visit to the States in 1923, he wrote that, “it was a great pleasure to meet Miss Ferber. The quality of her work is [as] undeniable as her personality.”

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When novelist Joseph Conrad encountered her on a visit to the States in 1923, he wrote that, “it was a great pleasure to meet Miss Ferber. The quality of her work is [as] undeniable as her personality.”

more here.

Manet’s Sources

Michael Fried at Artforum:

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Who Would Be a God?

“Oh, I would be a god”

—Lenny Everson

—A Debate in Poetry(with Lenny Everson).

Kitchener: Passion Among the Cacti Press, 2004.

Who would be a God?—Such juggling!

Scheduling rivers to run backwards

or a crack to lengthen and widen

boiling up black smokers beneath the sea.

And what to do about Popo Chang’s petunias

soccer-balled by red-necked boys,

or Antarctica melting,

while ants wobble a giant breadcrumb

toward their hungry mountain of sand?

The bluest skies have ignited with suicide drones.

Within the next sixty seconds,

how many thousand more

babies—which genes? what gender?—should be conceived?

Churches, synagogues, mosques, gutters, or temples,

the centuries’ dizzying Babel deafens.

Infinities of invisible sprockets!

From orbits to neutrons, keep all spinning

across string theory’s ten dimensions.

What of that fat firecracker, chaos?

Forever its sizzle is so tempting

to shatter every well-oiled cam and pinion

in any present and possible universe.

Isn’t mere mortal fussing enough of a headache

—to dig from clean laundry two navy socks that match

and remember not to sprinkle the cactus

except every fifteenth day,

let alone halt wars, seed famines,

and recharge a global economy?

Each body is, after all, a whole cosmos

revolving joints in their sockets,

dodging those rogue asteroids

cancer, Parkinson’s, pneumonia,

not to mention woofing and warping

around space-time’s white hole,

the soul.

Too much!

God only knows.

Susan Ioannou

from Ygdrasil, December 2003

Sunday, January 22, 2023

Here’s the truth about how to spot when someone is lying

Tim Brennen in Psyche:

Indeed, the study of lying is at least a century old, and thousands of scientific papers have been published. Researchers have mainly focused on the two key questions raised by that quote from Freud and the anecdote from India, namely: how good is the average person at detecting lies; and what, if any, are the behavioural signs of lying?

Indeed, the study of lying is at least a century old, and thousands of scientific papers have been published. Researchers have mainly focused on the two key questions raised by that quote from Freud and the anecdote from India, namely: how good is the average person at detecting lies; and what, if any, are the behavioural signs of lying?

To answer the first question, researchers have typically shown participants video clips of people telling a story. In some studies, the videos are from real life, in other studies they are artificial, but in all cases the researcher knows which ones show someone telling the truth and which show someone lying, and the job of the research participants is to decide for each clip whether the person is lying or not.

More here.

For whales, study shows gigantism is in the genes

Will Dunham at Reuters:

The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs.

The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs.

How did these magnificent marine mammals get so big? A new study explored the genetic underpinnings of gigantism in whales, identifying four genes that appear to have played crucial roles. These genes, the researchers said, helped in fostering great size but also in mitigating related disadvantageous consequences including higher cancer risk and lower reproductive output.

More here.

A tragedy pushed to the shadows: the truth about China’s Cultural Revolution

Tania Branigan in The Guardian:

In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by Mao Zedong as the shock troops of the Cultural Revolution – were to begin new lives in the countryside. A tide of youth swept towards impoverished villages. Auntie Huang and her friends were among them. Seventeen million teenagers, enough to populate a nation of their own, were sent hundreds of miles away, to places with no electricity or running water, some unreachable by road. The party called it “going up to the mountains and down to the countryside”, indicating its lofty justification and the humble soil in which these students were to set down roots. Some were as young as 14. Many had never spent a night away from home.

In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by Mao Zedong as the shock troops of the Cultural Revolution – were to begin new lives in the countryside. A tide of youth swept towards impoverished villages. Auntie Huang and her friends were among them. Seventeen million teenagers, enough to populate a nation of their own, were sent hundreds of miles away, to places with no electricity or running water, some unreachable by road. The party called it “going up to the mountains and down to the countryside”, indicating its lofty justification and the humble soil in which these students were to set down roots. Some were as young as 14. Many had never spent a night away from home.

These educated urban youth were to be reeducated. Their skills and knowledge would drag forward villages mired in poverty and ignorance, improving hygiene, spreading literacy, eradicating superstitions. But the peasantry’s task, in turn, was to uproot a more profound form of ignorance: the urban elite’s indifference to the masses. Mao had seized on the rural poor as the engine of revolution, bringing the Communist party to power. Now they were to remake this young generation – teaching them to live with nothing, to endure, even love, the dirtiest labour; to not merely sacrifice but efface themselves for the greater good. The reformed teenagers would bear his revolution to its ultimate triumph: a country whose society and culture were as communist as its political system.

More here.

An Economist Breaks Down a Fundamental Misunderstanding of the Cause of Poverty in Poor Countries

Ha-Joon Chang in Literary Hub:

If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

As a result, people in tropical countries don’t have to work hard to survive and consequently become less industrious. This idea is often expressed—mostly in private, given the offensive nature of the argument—using coconut.

More here.

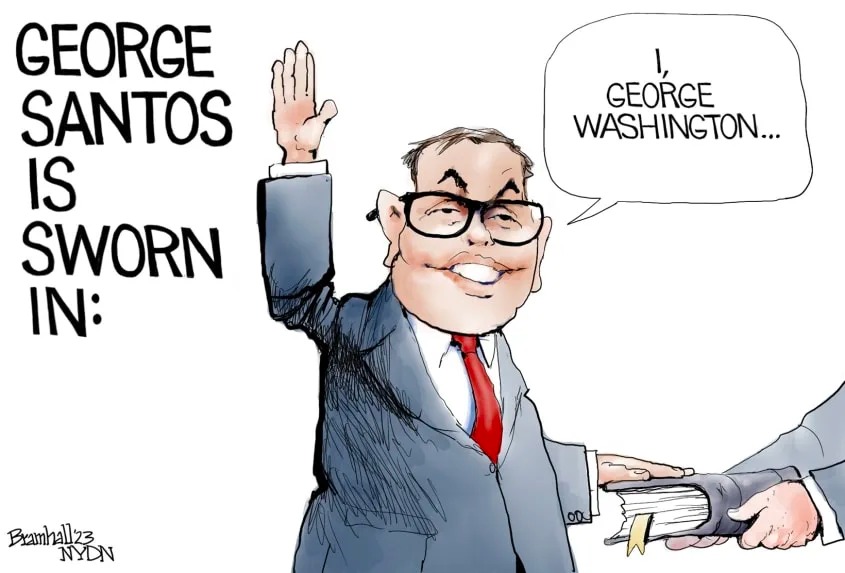

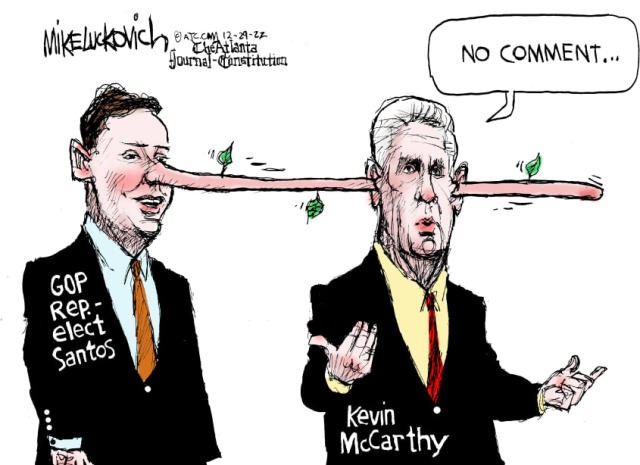

7 scathingly funny cartoons about George Santos’ lies

Nancy Pelosi, Liberated and Loving It

Maureen Dowd in The New York Times:

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.

Donald Trump was so freaked out at losing power that he was willing to destroy the country to keep it. I went to lunch with Nancy Pelosi at the Four Seasons to find out how she was faring, now that she has gone from being one of the most powerful women in the world — second in line to the presidency — and one of the most formidable speakers in American history to a mere House backbencher.

I was expecting King Lear, howling at the storm, but I found Gene Kelly, singing in the rain. Pelosi was not crying in her soup. She was basking as she scarfed down French fries, a truffle-butter roll and chocolate-covered macadamia nuts — all before the main course. She was literally in the pink, ablaze in a hot-pink pantsuit and matching Jimmy Choo stilettos, shooting the breeze about Broadway, music and sports. Showing off her four-inch heels, the 82-year-old said, “I highly recommend suede because it’s like a bedroom slipper.”

More here.

Sunday Poem

Letter From My Ancestors

We wouldn’t write this,

wouldn’t even think of it. We are working

people without time on our hands. In the old country,

we milk cows or deliver the mail or leave,

scattering to South Africa, Connecticut, Missouri,

and finally California for the Gold Rush—

Aaron and Lena run the Yosemite campground, general

store, a section of the stagecoach line. Morris comes

later, after the earthquake, finds two irons

and a board in the rubble of San Francisco.

Plenty of prostitutes need their dresses pressed, enough

to earn him the cash to open a haberdashery and marry

Sadie—we all have stories, yes, but we’re not thinking

stories. We have work to do, and a dozen children. They’ll

go on to pound nails and write up deals. Not musings.

We document transactions. Our diaries record

temperatures, landmarks, symptoms. We

do not write our dreams. We place another order.

make the next delivery, save the next

dollar, give another generation—you,

maybe—the luxury of time

to write about us.

by Krista Benjamin

from The Best American Poetry 2006

Scribner Poetry, 2006

Saturday, January 21, 2023

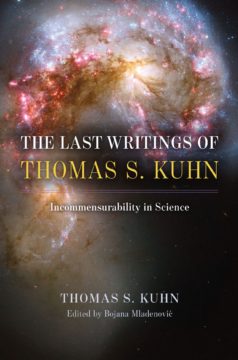

Competing Paradigms: On “The Last Writings of Thomas S. Kuhn”

Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

DELIVERING THE SHEARMAN Memorial Lectures at University College, London, in November 1987, Thomas Kuhn reflected on the moment that launched his philosophical career. He had been a graduate student at the time, preparing the obligatory freshman survey course in the history of science, and trying to understand how anyone ever accepted Aristotelian physics. Kuhn vividly recalls gazing out of his window for some time before suddenly grasping that Aristotle had meant something very different by “motion” from his Newtonian successors. Aristotle’s notion was broader: it encompassed how an acorn grows into an oak, or how the healthy decline into sickness, rather than just how physical objects move from one location to another. Many of the apparent absurdities of his theory — the impossibility of a projectile continuing to move once released from its source — were actually the result of reading contemporary concepts of motion back into his text. It was essentially a problem of translation: of not being able to think oneself into an entirely different world, and not simply a problem of trying to capture the nuance of the original Greek. Put simply, two different eras could not be expected to carve nature along the same joints.

Kuhn’s insight would overturn how we think about scientific progress. The traditional model had assumed a steady process of conjecture and refutation, beginning from a body of self-evident observations (the stone drops, this iron rusts, that raven is black) from which we infer universal generalizations; ongoing tweaks then further refine the theory for the purposes of ever better predictive accuracy.

More here.

Has Academia Ruined Literary Criticism?

Merve Emre in The New Yorker:

Merve Emre in The New Yorker:

If the character sketches that the English satirist Samuel Butler wrote in the mid-seventeenth century—among them “A Degenerate Noble,” “A Huffing Courtier,” “A Small Poet,” and “A Romance Writer”—the most recognizable today is “A Modern Critic.” He is a contemptible creature: a tyrant, a pedant, a crackpot, and a snob; “a very ungentle Reader”; “a Corrector of the Press gratis”; “a Committee-Man in the Commonwealth of letters”; “a Mountebank, that is always quacking of the infirm and diseased Parts of Books.” He judges, and, if authors are to be believed, he judges poorly. He praises without discernment. He invents faults when he cannot find any. Beholden to no authority, obeying nothing but the mysterious stirrings of his heart and his mind, he hands out dunce caps and placards insolently and with more than a little glee. Authors may complain to their friends, but they have no recourse. The critic’s word is law.

Butler’s sketch would still strike a chord with aggrieved writers today, but, in his time, the Modern Critic—part mountebank, part magician—was a new phenomenon. The figure’s shape-shifting in the centuries since is the subject of John Guillory’s new book, “Professing Criticism” (Chicago), an erudite and occasionally biting series of essays on “the organization of literary study.” Guillory has spent much of his career explaining how works of literature are enjoyed, assessed, interpreted, and taught; he is best known for his landmark work, “Cultural Capital” (1993), which showed how literary evaluation draws authority from the institutions—principally universities—within which it is practiced. To suggest, for instance, that minor poets were superior to major ones, as T. S. Eliot did, or that the best modernist poetry was inferior to the best modernist prose, as Harold Bloom did, meant little unless these judgments could be made to stick—that is, unless there were mechanisms for transmitting these judgments to other readers. (Full disclosure: I have written an introduction to a forthcoming thirtieth-anniversary edition of the book.)

More here.

Sectional Industrialization

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Few scholars have done more to elucidate the relationship between democracy and economic development in the United States and its corresponding regional—or “sectional”—antagonisms than Richard Franklin Bensel, the Gary S. Davis professor of government at Cornell University. Among Bensel’s published works are Sectionalism and American Political Development, 1880-1980 (1984), Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859-1877 (1990), and The Political Economy of American Industrialization, 1877-1900 (2000), all of which introduce key arguments about the course of US political economy that remain critical to understanding the evolution of the two-party system and its cross-class coalitions.

The first book measures key moments of “sectional stress” between the industrial core of the United States and the parts of the country that were traditionally agrarian and underdeveloped before the postwar decades. In his treatment of the House of Representatives as an institution which primarily represents “trade delegations,” Bensel demonstrates that a fundamental core-periphery dynamic persisted over the course of the twentieth century even as the South industrialized and the geographic poles of the Republican and Democratic parties reversed. In particular, he tracks the rise and fall of the Democratic Party’s bipolar coalition and the party’s deepening support for the most economically advanced regions of the US, anticipating today’s polarization between large, prosperous metropolitan areas and rural and peri-urban counties.

More here.

Latour’s Metamorphosis

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

When the multi-hyphenate scholar of science Bruno Latour died last October at the age of 75, tributes poured in from all corners of academia and many beyond. In the aughts, Latour had been a ubiquitous reference point for Anglophone social and cultural theory, standing alongside Judith Butler and Michel Foucault on the list of most cited academics in fields ranging from geography to art history. Made notorious by the ‘Science Wars’ of the 1990s, he reinvented himself as a climate scholar and public intellectual in the last two decades of his life. Yet amidst the expressions of appreciation and grief, many on the left shrugged. Latour’s relationship to the left had long been fraught, if not entirely unsatisfactory to either: Latour enjoyed antagonizing the left; in turn, many leftists loved to hate Latour. His ascendance in the politically bleak years of the early twenty-first century was to many damning. And yet as he sought to respond to the political challenge of climate change in his final years, he turned, in his own deeply idiosyncratic way, to consider questions of production and class; transformation and struggle.

Latour was candid about his own background, readily acknowledging he hailed from the ‘typical French provincial bourgeoisie’. Born in 1947 in Beaune, Latour was the eighth child of a well-known Catholic winemaking family – proprietors of Maison Louis Latour, known for their Grand Cru Burgundys. With his older brother already slated to take over the family business, Latour was sent to Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague, a selective Jesuit private school in Paris. A leading placement in the agrégation led to a doctorate in theology from the Université de Tours. Twenty-one in 1968, Latour could be found not in the streets of Paris but the lecture halls of Dijon, where he studied biblical exegesis with the scholar and former Catholic priest André Malet. He wrote his dissertation on Charles Péguy, while working in the French civilian service in Abidjan, then capital of Côte d’Ivoire. There he was charged with conducting a survey on the ‘ideology of competence’ for a French development agency seeking to understand the absence of Ivoirians from managerial roles, while reading Anti-Oedipus by night. (‘Deleuze is in my bones’, he would later claim.)

More here.

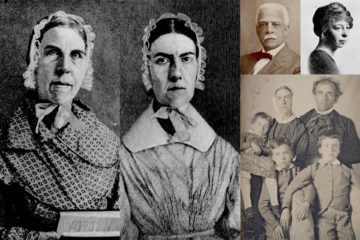

Slavery’s Indelible Stain on a White Abolitionist Legend

Michael Jeffries in The New York Times:

Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?”

Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?”

The Grimke sisters became celebrities, publishing essays that shaped abolitionist thinking and reluctantly stepping into a male-dominated public sphere where they were never completely welcome. Their fame derived from both their words and their deeds. They rejected their white inheritance by coming north and joining the movement, gaining moral credibility that few of their peers could match. But in her new book, “The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family,” the historian Kerri Greenidge challenges this narrative, showing that the sisters’ contributions to abolition and women’s rights were undergirded by the privileges they reaped from slavery. The lives they built, and their relationships with Black relatives, were poisoned by the profits, violence and shame of white supremacy.

More here.

A joke with a literal cost

Emily Stewart in Vox:

This is not a thing anymore.

This is not a thing anymore.

That’s how Josh Brown, market commentator and CEO of Ritholtz Wealth Management, responded when I told him I was writing about meme stocks in the fall of 2022, his tone one generally reserved for a parent who isn’t mad, just disappointed. “It was fascinating at the time, but it’s way past,” he said, likening covering GameStop today to writing about Soulja Boy and the Macarena.

You see, at the start of 2021, a handful of stocks gained a cult-like following online. An army of retail traders — people who invest with their own money instead of on behalf of a group or institution — who gathered largely on the Reddit forum r/WallStreetBets were able to drive up the share prices of video game retailer GameStop, movie theater chain AMC, and some other relatively small companies. Part of their strategy involved orchestrating a “short squeeze” against big funds that were betting against the stocks by shorting them.

More here.