Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

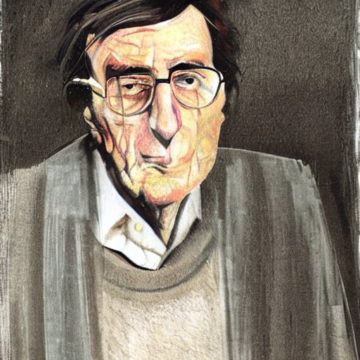

When the multi-hyphenate scholar of science Bruno Latour died last October at the age of 75, tributes poured in from all corners of academia and many beyond. In the aughts, Latour had been a ubiquitous reference point for Anglophone social and cultural theory, standing alongside Judith Butler and Michel Foucault on the list of most cited academics in fields ranging from geography to art history. Made notorious by the ‘Science Wars’ of the 1990s, he reinvented himself as a climate scholar and public intellectual in the last two decades of his life. Yet amidst the expressions of appreciation and grief, many on the left shrugged. Latour’s relationship to the left had long been fraught, if not entirely unsatisfactory to either: Latour enjoyed antagonizing the left; in turn, many leftists loved to hate Latour. His ascendance in the politically bleak years of the early twenty-first century was to many damning. And yet as he sought to respond to the political challenge of climate change in his final years, he turned, in his own deeply idiosyncratic way, to consider questions of production and class; transformation and struggle.

Latour was candid about his own background, readily acknowledging he hailed from the ‘typical French provincial bourgeoisie’. Born in 1947 in Beaune, Latour was the eighth child of a well-known Catholic winemaking family – proprietors of Maison Louis Latour, known for their Grand Cru Burgundys. With his older brother already slated to take over the family business, Latour was sent to Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague, a selective Jesuit private school in Paris. A leading placement in the agrégation led to a doctorate in theology from the Université de Tours. Twenty-one in 1968, Latour could be found not in the streets of Paris but the lecture halls of Dijon, where he studied biblical exegesis with the scholar and former Catholic priest André Malet. He wrote his dissertation on Charles Péguy, while working in the French civilian service in Abidjan, then capital of Côte d’Ivoire. There he was charged with conducting a survey on the ‘ideology of competence’ for a French development agency seeking to understand the absence of Ivoirians from managerial roles, while reading Anti-Oedipus by night. (‘Deleuze is in my bones’, he would later claim.)

More here.