Omari Edwards at IAI News:

Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly?

Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly?

I have to say that reductionism plays a rather ambiguous role in my work, and I think in the work of most scientists. Of course, there are some necessities about the scientific method which mean that the only way we can answer certain questions is by reducing a problem to its fundamentals. However, I think this misses out on what scientists are really doing. We aren’t trying to just give a reductive account we are always working within a framework. And that framework is going to be synthetic.

More here.

While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism.

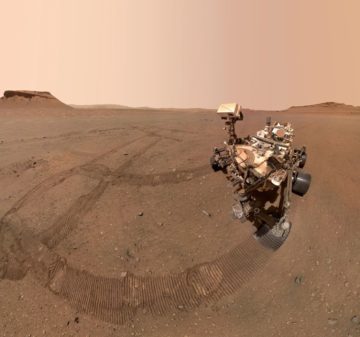

While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism. For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission.

For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission. “Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973. Drug overdose deaths have

Drug overdose deaths have  As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured.

As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured. On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid.

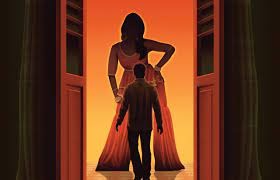

On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid. Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home.

Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home. “Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.”

“Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.” Jacob Browning and Yann Lecun in Noema:

Jacob Browning and Yann Lecun in Noema: David Van Reybrouk in Noema:

David Van Reybrouk in Noema: Daniel Bessner in Boston Review:

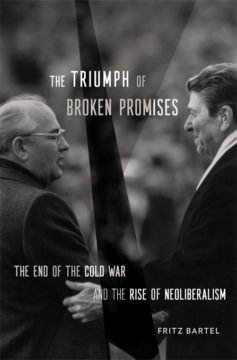

Daniel Bessner in Boston Review: Max Krahé in Phenomenal World:

Max Krahé in Phenomenal World: I

I