Emily C. Friedman in the LA Review of Books:

Emily C. Friedman in the LA Review of Books:

IN LATE FEBRUARY, Twitter user @ACassDarkly reported the following bewildering conversation around the new film Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, which debuted last weekend:

Person: “I can’t wait for the Dungeons & Dragons movie.”

Me: “Yeah it looks pretty fun.”

Person: “Do you think they’ll stick to the story?”

Me: “…?”

Person: “I just hate it when movies like that don’t stick to the story.”

Me: “The story of Dungeons & Dragons?”

This exchange is humorous because the popular tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons has no story—or rather, it has hundreds of thousands of stories, crafted at tables around the world, in dozens of languages, by the estimated 50 million current players. Or, as Chris Perkins, senior story designer for D&D, said last week in a promotional D&D Direct event, “What we write, you bring to life.”

But what Wizards of the Coast, the publisher of D&D, writes and sells is only a small portion of the creative material available to players. Game mechanics are not protected by copyright, and the imagined worlds owned by Wizards (such as the Forgotten Realms, the fantasy setting in which Honor Among Thieves takes place) are not required to play the game. “Homebrew” adventures, creatures, settings, and more have always been part of D&D, and over the past two decades, the Open Game License (or OGL) has allowed third-party creators to monetize their creative output with remarkably few restrictions. Publishing D&D content independently or with third-party publishers has now become an established pathway toward working on official D&D products with Wizards. The tabletop role-playing industry as a whole boomed under the OGL, as new companies have formed to provide both supplementary material for D&D and to incubate new game systems.

More here.

From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors.

From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors.

In the US and around the world, people are

In the US and around the world, people are  I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!”

I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!” We’re supposedly on the brink of an artificial intelligence breakthrough. The bots are already communicating—at least they’re stringing together words and creating images. Some of those images are even kind of cool, especially if you’re into that sophomore dorm room surrealist aesthetic. GPT-3, and, more recently, chatGPT, two tools from OpenAI (which recently

We’re supposedly on the brink of an artificial intelligence breakthrough. The bots are already communicating—at least they’re stringing together words and creating images. Some of those images are even kind of cool, especially if you’re into that sophomore dorm room surrealist aesthetic. GPT-3, and, more recently, chatGPT, two tools from OpenAI (which recently  A small international team of molecular and evolutionary scientists has discovered that male yellow crazy ants (also known as long-legged ants) have two sets of DNA throughout their bodies. In their paper published in the journal Science, the group describes the unique find and discusses possible reasons for it. Daniel Kronauer with The Rockefeller University has published a Perspective piece in the same journal issue discussing the work by the team and suggests that the unique genetic feature of the ants may explain why they are such a successful invasive species.

A small international team of molecular and evolutionary scientists has discovered that male yellow crazy ants (also known as long-legged ants) have two sets of DNA throughout their bodies. In their paper published in the journal Science, the group describes the unique find and discusses possible reasons for it. Daniel Kronauer with The Rockefeller University has published a Perspective piece in the same journal issue discussing the work by the team and suggests that the unique genetic feature of the ants may explain why they are such a successful invasive species. Emily C. Friedman in the LA Review of Books:

Emily C. Friedman in the LA Review of Books: Dylan Riley in Sidecar:

Dylan Riley in Sidecar:

The effect of Ernaux’s diary is to make this clear: These are the places where life happens, where the social orders are made apparent and reinforced, where societies are “built.” Her local big-box store is the site of ideas, feelings and consequential interactions, where the politics of class, race, gender and privilege get played out — along with more private fantasies and reveries.

The effect of Ernaux’s diary is to make this clear: These are the places where life happens, where the social orders are made apparent and reinforced, where societies are “built.” Her local big-box store is the site of ideas, feelings and consequential interactions, where the politics of class, race, gender and privilege get played out — along with more private fantasies and reveries. Bruno Schulz was a gnomish, cockeyed Polonophone Jew whose writing gave sophisticated expression to the wondrous vagary and uncertainty and foreboding of childhood, without forcing it to — actually, without letting it — grow up. His two volumes of fiction — the sum total of his surviving work save a few scraps that, given Schulz’s focus on youth, one hesitates to call juvenilia — are rife with how small it can feel to be small; they are claustral with the creeping tensions and melancholy of adult domesticity, and slyly attentive to the vulnerability of boredom that can, suddenly, crashingly, turn one’s head to sex.

Bruno Schulz was a gnomish, cockeyed Polonophone Jew whose writing gave sophisticated expression to the wondrous vagary and uncertainty and foreboding of childhood, without forcing it to — actually, without letting it — grow up. His two volumes of fiction — the sum total of his surviving work save a few scraps that, given Schulz’s focus on youth, one hesitates to call juvenilia — are rife with how small it can feel to be small; they are claustral with the creeping tensions and melancholy of adult domesticity, and slyly attentive to the vulnerability of boredom that can, suddenly, crashingly, turn one’s head to sex. A

A Sending threatening text messages to a female colleague. Making fun of another woman by mimicking her on the air. Asking a co-anchor if, perhaps, she was having trouble remembering a statistic in the newscast because she had “mommy brain.” These are just a few of the allegations — many of them captured on camera for the world to see — leveled at CNN anchor Don Lemon in

Sending threatening text messages to a female colleague. Making fun of another woman by mimicking her on the air. Asking a co-anchor if, perhaps, she was having trouble remembering a statistic in the newscast because she had “mommy brain.” These are just a few of the allegations — many of them captured on camera for the world to see — leveled at CNN anchor Don Lemon in  It is a warm, clear spring morning and Ai Weiwei is giving me a tour of the huge new studio he is building about an hour’s drive from Lisbon. There is not another house in sight, just the flat green landscape of the Alentejo, and a big blue sky dotted with darting swallows. The studio, explains the artist, is a replica of his old one in Shanghai, which was finished in 2011 only to be almost immediately

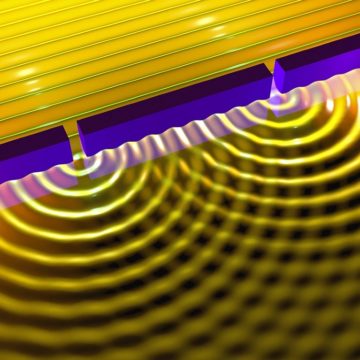

It is a warm, clear spring morning and Ai Weiwei is giving me a tour of the huge new studio he is building about an hour’s drive from Lisbon. There is not another house in sight, just the flat green landscape of the Alentejo, and a big blue sky dotted with darting swallows. The studio, explains the artist, is a replica of his old one in Shanghai, which was finished in 2011 only to be almost immediately  A celebrated experiment in 1801 showed that light passing through two thin slits interferes with itself, forming a characteristic striped pattern on the wall behind. Now, physicists have shown that a similar effect can arise with two slits in time rather than space: a single mirror that rapidly turns on and off causes interference in a laser pulse, making it change colour.

A celebrated experiment in 1801 showed that light passing through two thin slits interferes with itself, forming a characteristic striped pattern on the wall behind. Now, physicists have shown that a similar effect can arise with two slits in time rather than space: a single mirror that rapidly turns on and off causes interference in a laser pulse, making it change colour.