Liz Kimbrough in Mongabay:

When it comes to climate solutions, your first thought may not be the wildebeest. But in the Serengeti, these buffalo-looking antelopes are the key to carbon capture.

When it comes to climate solutions, your first thought may not be the wildebeest. But in the Serengeti, these buffalo-looking antelopes are the key to carbon capture.

Wildebeest eat large amounts of grass and recycle it back into the soil as dung. So when their population plummeted in the early 1900s due to a disease transmitted from domestic cattle, the loss of natural grazing led to more frequent and intense wildfires, turning the Serengeti into a carbon source.

Efforts to bring back or “rewild” the wildebeest population through disease management were a huge success, helping reduce the frequency and intensity of wildfires, and restoring the Serengeti back into a carbon sink.

Trophic rewilding, or restoring and protecting the functional roles of animals in ecosystems, is an overlooked climate change solution, says a new report published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change.

More here.

A major ocean circulation that forms around Antarctica could be headed for collapse, risking significant changes to the world’s weather, sea levels and the health of marine ecosystems, scientists say, offering a stark warning about the growing impacts of climate change.

A major ocean circulation that forms around Antarctica could be headed for collapse, risking significant changes to the world’s weather, sea levels and the health of marine ecosystems, scientists say, offering a stark warning about the growing impacts of climate change. The Covid-19 pandemic has wreaked extraordinary destruction and misery, killing nearly 7 million people worldwide thus far and devastating the lives of many more. And yet, viewed through the long lens of human history, writes the public health sociologist Jonathan Kennedy, “there is little about it that is new or remarkable”. Previous pandemics have killed many more, both in absolute numbers and as proportions of populations, and so may future ones. Covid should be a wakeup call that helps us manage deadlier plagues in the future. But will we heed it?

The Covid-19 pandemic has wreaked extraordinary destruction and misery, killing nearly 7 million people worldwide thus far and devastating the lives of many more. And yet, viewed through the long lens of human history, writes the public health sociologist Jonathan Kennedy, “there is little about it that is new or remarkable”. Previous pandemics have killed many more, both in absolute numbers and as proportions of populations, and so may future ones. Covid should be a wakeup call that helps us manage deadlier plagues in the future. But will we heed it? Air pollution could cause lung cancer not by mutating DNA, but by creating an inflamed environment that encourages proliferation of cells with existing cancer-driving mutations, according to a sweeping study of human health data and experiments in laboratory mice. The results, published in Nature on 5 April

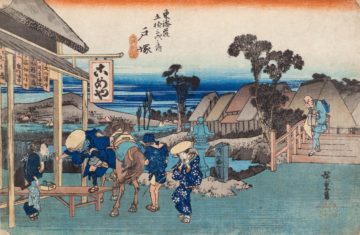

Air pollution could cause lung cancer not by mutating DNA, but by creating an inflamed environment that encourages proliferation of cells with existing cancer-driving mutations, according to a sweeping study of human health data and experiments in laboratory mice. The results, published in Nature on 5 April A major exhibition on the art and influence of Japanese printmaker Katsushika Hokusai

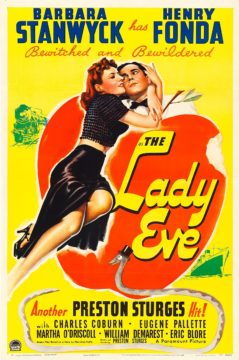

A major exhibition on the art and influence of Japanese printmaker Katsushika Hokusai  Klawans, like many before him, notes the echoes of Sturges’s life in his work: the juxtaposition of bohemians and stern squares, the fluency in both American vernacular and European argot, the linking of slapstick and hypocrisy. But he also wants to make this reading “wobble a bit,” and he peers between every snappy line for cultural references, Biblical allegories, political sympathies, and philosophies about love and suffering. A Sturges film, Klawans believes, is more than just its witty banter: “One of the chief distractions from thinking your way through the films is their most universally admired trait: the dialogue.”

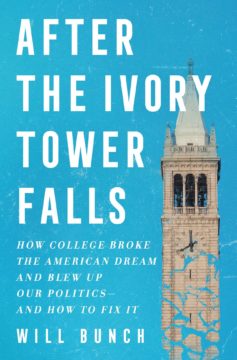

Klawans, like many before him, notes the echoes of Sturges’s life in his work: the juxtaposition of bohemians and stern squares, the fluency in both American vernacular and European argot, the linking of slapstick and hypocrisy. But he also wants to make this reading “wobble a bit,” and he peers between every snappy line for cultural references, Biblical allegories, political sympathies, and philosophies about love and suffering. A Sturges film, Klawans believes, is more than just its witty banter: “One of the chief distractions from thinking your way through the films is their most universally admired trait: the dialogue.” Talk-show host Rush Limbaugh, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom under former president Donald Trump, relied on his listeners’ resentment of college-educated folks throughout the 1990s to stoke the fires of culture war. There was something about what colleges did that convinced many of Limbaugh’s listeners that, in journalist Will Bunch’s words, “nothing in America made sense anymore.” And it was this confusion, Bunch argues in his new book, After the Ivory Tower Falls: How College Broke the American Dream and Blew Up Our Politics—and How to Fix It, that produced the biggest divide in American politics, between those with and without college degrees. Rather than dismiss the concerns of Limbaugh’s listeners, Bunch takes them seriously. They are not wrong to sense that “the American way of college went off the rails,” Bunch concludes.

Talk-show host Rush Limbaugh, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom under former president Donald Trump, relied on his listeners’ resentment of college-educated folks throughout the 1990s to stoke the fires of culture war. There was something about what colleges did that convinced many of Limbaugh’s listeners that, in journalist Will Bunch’s words, “nothing in America made sense anymore.” And it was this confusion, Bunch argues in his new book, After the Ivory Tower Falls: How College Broke the American Dream and Blew Up Our Politics—and How to Fix It, that produced the biggest divide in American politics, between those with and without college degrees. Rather than dismiss the concerns of Limbaugh’s listeners, Bunch takes them seriously. They are not wrong to sense that “the American way of college went off the rails,” Bunch concludes. Within the past decade, scientists have discovered a class of materials that, at extreme pressures, show superconductivity at temperatures just a few tens of degrees below freezing, but the goal of a room-temperature superconductor has remained out of reach. In

Within the past decade, scientists have discovered a class of materials that, at extreme pressures, show superconductivity at temperatures just a few tens of degrees below freezing, but the goal of a room-temperature superconductor has remained out of reach. In  Recently, I argued in this publication that one of our best guides to the world of social media is

Recently, I argued in this publication that one of our best guides to the world of social media is  There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy. All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented.

All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented. Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality.

Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality. A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it.

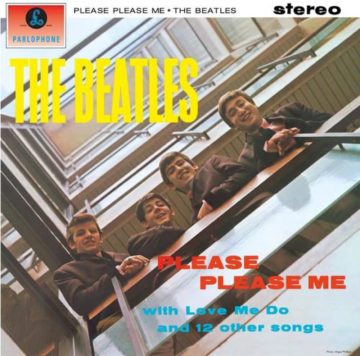

A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it. Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.”

Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.”