Mark Rollins in The Common Reader:

In 1961, the Jaguar E-type sports car (called the XKE in the United States), designed by Malcolm Sayer, premiered at a major auto show in Geneva Switzerland. Enzo Ferrari declared it to be the most beautiful car ever made. Ferrari himself is, of course, a legendary figure in the history of car design. Ferrari’s judgment was thus stunning in a certain respect. It is very common for cars to be put into stereotypical national, cultural, or ethnic categories. So, for example, there are sleek Italian sports cars, elegant but staid British sedans, and powerful American “muscle” cars. Ferrari’s assessment unsettled these standard categories. This was an Italian expert heaping praise on the beauty of a British car.

In 1961, the Jaguar E-type sports car (called the XKE in the United States), designed by Malcolm Sayer, premiered at a major auto show in Geneva Switzerland. Enzo Ferrari declared it to be the most beautiful car ever made. Ferrari himself is, of course, a legendary figure in the history of car design. Ferrari’s judgment was thus stunning in a certain respect. It is very common for cars to be put into stereotypical national, cultural, or ethnic categories. So, for example, there are sleek Italian sports cars, elegant but staid British sedans, and powerful American “muscle” cars. Ferrari’s assessment unsettled these standard categories. This was an Italian expert heaping praise on the beauty of a British car.

About 35 years later, Ferrari’s assessment would seem to have been vindicated. A version of the original Jaguar E-type was put on display in the Museum of Modern Art. It could be argued then that what Ferrari called the most beautiful car ever made—a functional design object—had finally come to be seen as a work of art.

More here.

A

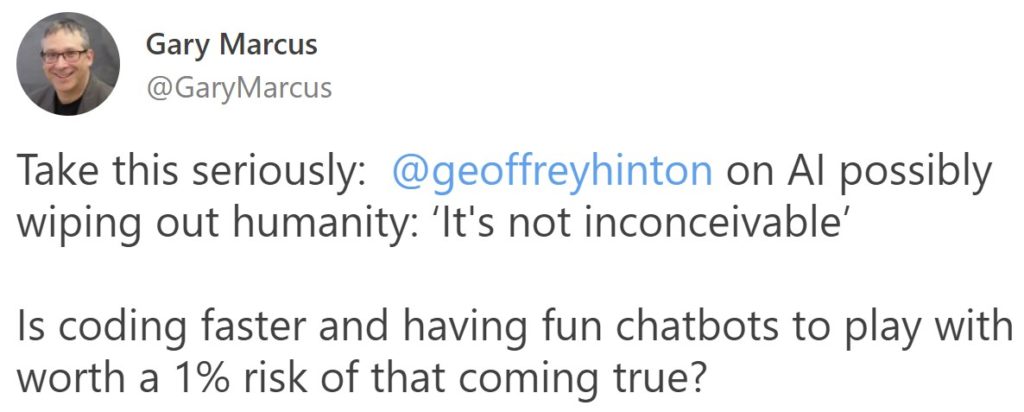

A The incessant hype over AI tools like ChatGPT is inspiring lots of bad opinions from people who have no idea what they’re talking about. From a New York Times columnist

The incessant hype over AI tools like ChatGPT is inspiring lots of bad opinions from people who have no idea what they’re talking about. From a New York Times columnist

For more than a decade, scholars, journalists, and tech leaders have focused on two ways that data-driven technologies are altering jobs: by automating tasks and therefore displacing certain workers, and by discriminating on the basis of race, sex, national origin, or disability. Those are critical issues, but surveillance technologies are having another effect on work as well. Companies across today’s vast service economy are using such technologies as tools of class domination, deploying them to limit wage growth, prevent workers from organizing, and enhance labor exploitation. Workers’ increasing resistance to surveillance is therefore also a process of class formation—and reforms that support such resistance could encourage a more democratic politics of workplace technology.

For more than a decade, scholars, journalists, and tech leaders have focused on two ways that data-driven technologies are altering jobs: by automating tasks and therefore displacing certain workers, and by discriminating on the basis of race, sex, national origin, or disability. Those are critical issues, but surveillance technologies are having another effect on work as well. Companies across today’s vast service economy are using such technologies as tools of class domination, deploying them to limit wage growth, prevent workers from organizing, and enhance labor exploitation. Workers’ increasing resistance to surveillance is therefore also a process of class formation—and reforms that support such resistance could encourage a more democratic politics of workplace technology.

INTERVIEWER

INTERVIEWER In the summer of 2021, I experienced a cluster of coincidences, some of which had a distinctly supernatural feel. Here’s how it started. I keep a journal and record dreams if they are especially vivid or strange. It doesn’t happen often, but I logged one in which my mother’s oldest friend, a woman called Rose, made an appearance to tell me that she (Rose) had just died. She’d had another stroke, she said, and that was it. Come the morning, it occurred to me that I didn’t know whether Rose was still alive. I guessed not. She’d had a major stroke about

In the summer of 2021, I experienced a cluster of coincidences, some of which had a distinctly supernatural feel. Here’s how it started. I keep a journal and record dreams if they are especially vivid or strange. It doesn’t happen often, but I logged one in which my mother’s oldest friend, a woman called Rose, made an appearance to tell me that she (Rose) had just died. She’d had another stroke, she said, and that was it. Come the morning, it occurred to me that I didn’t know whether Rose was still alive. I guessed not. She’d had a major stroke about  Researchers at University of Oxford have recently created a quantum memory within a trapped-ion quantum network node. Their unique memory design, introduced in a paper in Physical Review Letters, has been found to be extremely robust, meaning that it could store information for long periods of time despite ongoing network activity. “We are building a network of quantum computers, which use trapped ions to store and process quantum information,” Peter Drmota, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “To connect quantum processing devices, we use

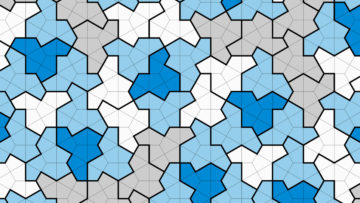

Researchers at University of Oxford have recently created a quantum memory within a trapped-ion quantum network node. Their unique memory design, introduced in a paper in Physical Review Letters, has been found to be extremely robust, meaning that it could store information for long periods of time despite ongoing network activity. “We are building a network of quantum computers, which use trapped ions to store and process quantum information,” Peter Drmota, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “To connect quantum processing devices, we use  A 13-sided shape known as “the hat” has mathematicians tipping their caps.

A 13-sided shape known as “the hat” has mathematicians tipping their caps. The specter of parental neglect no longer orders U.S. politics as it did in the late twentieth century. But as indispensable recent books by sociologists Lynne Haney and Dorothy Roberts demonstrate, the knotty legal infrastructures and punitive policies inspired by this rhetoric have endured, with devastating consequences for poor families. These books focus on different areas of U.S. family policy—Haney writes about child support enforcement, Roberts about child protective services—but together they expose the state’s massive and creeping apparatus for surveilling and disciplining parents.

The specter of parental neglect no longer orders U.S. politics as it did in the late twentieth century. But as indispensable recent books by sociologists Lynne Haney and Dorothy Roberts demonstrate, the knotty legal infrastructures and punitive policies inspired by this rhetoric have endured, with devastating consequences for poor families. These books focus on different areas of U.S. family policy—Haney writes about child support enforcement, Roberts about child protective services—but together they expose the state’s massive and creeping apparatus for surveilling and disciplining parents. David Baddiel was six years old when his mother told him death was like a long sleep from which you never wake up. “I think from that point,” he says, “I never really wanted to go to sleep again.” That night, he lay on the top bunk of his bed, fervently praying – “probably” the first and last time he has prayed with any sincerity – that “my life as it was in Dollis Hill in 1971 would still somehow continue after death”.

David Baddiel was six years old when his mother told him death was like a long sleep from which you never wake up. “I think from that point,” he says, “I never really wanted to go to sleep again.” That night, he lay on the top bunk of his bed, fervently praying – “probably” the first and last time he has prayed with any sincerity – that “my life as it was in Dollis Hill in 1971 would still somehow continue after death”.