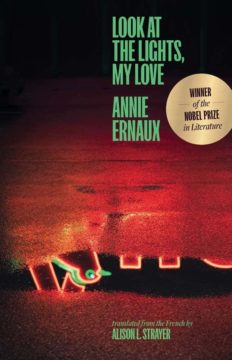

Category: Recommended Reading

A Sociological Deep-Dive Into Big-Box Stores

Kate Briggs at The Washington Post:

The effect of Ernaux’s diary is to make this clear: These are the places where life happens, where the social orders are made apparent and reinforced, where societies are “built.” Her local big-box store is the site of ideas, feelings and consequential interactions, where the politics of class, race, gender and privilege get played out — along with more private fantasies and reveries.

The effect of Ernaux’s diary is to make this clear: These are the places where life happens, where the social orders are made apparent and reinforced, where societies are “built.” Her local big-box store is the site of ideas, feelings and consequential interactions, where the politics of class, race, gender and privilege get played out — along with more private fantasies and reveries.

“Look at the lights, my love!” is an injunction a young mother makes to her child, pushing her up the moving walkway at Christmastime; Ernaux describes her own “rush of pleasure” at the prospect of interrupting her writing to drive to Auchan. Stores like this are frequented by the unemployed, adults with young children, the elderly, teenagers, the lonely, the homeless.

But, Ernaux points out, “when you think of it, there is no other space, public or private, where so many individuals so different in terms of age, income, education, geographic and ethnic background, and personal style, move about and rub shoulders with each other.”

more here.

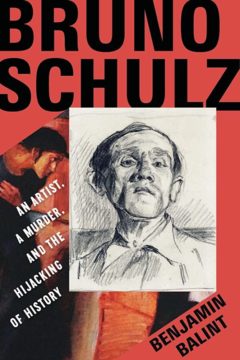

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, A Murder, And The Hijacking Of History

Joshua Cohen at the NY Times:

Bruno Schulz was a gnomish, cockeyed Polonophone Jew whose writing gave sophisticated expression to the wondrous vagary and uncertainty and foreboding of childhood, without forcing it to — actually, without letting it — grow up. His two volumes of fiction — the sum total of his surviving work save a few scraps that, given Schulz’s focus on youth, one hesitates to call juvenilia — are rife with how small it can feel to be small; they are claustral with the creeping tensions and melancholy of adult domesticity, and slyly attentive to the vulnerability of boredom that can, suddenly, crashingly, turn one’s head to sex.

Bruno Schulz was a gnomish, cockeyed Polonophone Jew whose writing gave sophisticated expression to the wondrous vagary and uncertainty and foreboding of childhood, without forcing it to — actually, without letting it — grow up. His two volumes of fiction — the sum total of his surviving work save a few scraps that, given Schulz’s focus on youth, one hesitates to call juvenilia — are rife with how small it can feel to be small; they are claustral with the creeping tensions and melancholy of adult domesticity, and slyly attentive to the vulnerability of boredom that can, suddenly, crashingly, turn one’s head to sex.

The family that recurs throughout his corpus, a family that resembles his own, dwells in a dim, dusty house of uncountable rooms, stuffed with tailors’ dummies, taxidermy and raggedy toys, frescoes, panoramas, postcards, stamp albums and theatrical props. This visual excess, which is matched and mismatched by Schulz’s bric-a-brac prose, enables one of the author’s signature techniques: the description of a thing through a description of an image of that thing.

more here.

‘I spent years studying death, but it didn’t prepare me for grief’

Sarah Tarlow in The Guardian:

At about 9.15 on the morning of 7 May 2016, I came home and found my husband of two weeks, my partner of 18 years, dead in bed. Still, I go over and over the way that morning unfolded. I woke at my brother Ben’s house. Since I had left Mark alone overnight for the first time in months, and because he could not get his own breakfast or medication, I set off to drive home as soon as I was dressed and had drunk a cup of tea.

At about 9.15 on the morning of 7 May 2016, I came home and found my husband of two weeks, my partner of 18 years, dead in bed. Still, I go over and over the way that morning unfolded. I woke at my brother Ben’s house. Since I had left Mark alone overnight for the first time in months, and because he could not get his own breakfast or medication, I set off to drive home as soon as I was dressed and had drunk a cup of tea.

I texted Mark to say I was setting off, but I got no reply. Like the previous day, it was gloriously warm and sunny, and my drive along the empty A1 was easy and quick. I parked the car and walked up to the front door. I let myself in and shouted up, “Hello. I’m home!” No answer. “Mark?” I started up the stairs. It was quite silent. I had a sick, empty feeling, as though all the organs in my abdomen had suddenly dropped about a foot. I sort of knew, but I did not absolutely know. Not yet. I thought to myself, “This is the last moment before our world changes; these are the last steps in my old life.”

More here.

The stubborn sexism of American politics

Anna North in Vox:

Sending threatening text messages to a female colleague. Making fun of another woman by mimicking her on the air. Asking a co-anchor if, perhaps, she was having trouble remembering a statistic in the newscast because she had “mommy brain.” These are just a few of the allegations — many of them captured on camera for the world to see — leveled at CNN anchor Don Lemon in a Variety report released on Wednesday. But Lemon was already facing increased scrutiny for voicing an extremely sexist opinion about a woman in a position of power. In February, Lemon pronounced, on air, that former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who recently announced her presidential bid, was not “in her prime.” Haley, at 51, is six years younger than Lemon.

Sending threatening text messages to a female colleague. Making fun of another woman by mimicking her on the air. Asking a co-anchor if, perhaps, she was having trouble remembering a statistic in the newscast because she had “mommy brain.” These are just a few of the allegations — many of them captured on camera for the world to see — leveled at CNN anchor Don Lemon in a Variety report released on Wednesday. But Lemon was already facing increased scrutiny for voicing an extremely sexist opinion about a woman in a position of power. In February, Lemon pronounced, on air, that former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who recently announced her presidential bid, was not “in her prime.” Haley, at 51, is six years younger than Lemon.

The comment prompted widespread condemnation from both the left and the right, as well as from Lemon’s colleagues, and he was absent from CNN for two days. Lemon has since apologized for the Haley comments and, through a CNN spokesperson, denied the allegations in the Variety story.

More here.

Saturday Poem

White Corn Boy

I am the White Corn Boy.

I walk in sight of my home.

I walk in plain sight of my home.

I walk on the straight path which is toward my home.

I walk to the entrance of my home.

I arrive at the beautiful goods curtain which hangs at the doorway.

I arrive at the entrance of my home.

I am in the middle of my home.

I am at the back of my home.

I am on top of the pollen foot print.

I am on top of the pollen seed print.

I am like the Most High Power Whose Ways Are Beautiful.

Before me it is beautiful.

Behind me it is beautiful.

Under me it is beautiful.

Above me it is beautiful.

All around me it is beautiful.

by Anonymous

from American Indian Prose and Poetry —

Before the White Man Came

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1974

Friday, April 7, 2023

Ai Weiwei finds peace in Portugal: ‘I could throw away all my art and not feel much’

Steve Rose in The Guardian:

It is a warm, clear spring morning and Ai Weiwei is giving me a tour of the huge new studio he is building about an hour’s drive from Lisbon. There is not another house in sight, just the flat green landscape of the Alentejo, and a big blue sky dotted with darting swallows. The studio, explains the artist, is a replica of his old one in Shanghai, which was finished in 2011 only to be almost immediately demolished by the Chinese authorities: officially, because it contravened planning regulations; unofficially, because of Ai’s outspoken criticism of the government. Months later, the artist was imprisoned for three months then placed under house arrest. When his passport was returned in 2015, he left the country and has not returned since.

It is a warm, clear spring morning and Ai Weiwei is giving me a tour of the huge new studio he is building about an hour’s drive from Lisbon. There is not another house in sight, just the flat green landscape of the Alentejo, and a big blue sky dotted with darting swallows. The studio, explains the artist, is a replica of his old one in Shanghai, which was finished in 2011 only to be almost immediately demolished by the Chinese authorities: officially, because it contravened planning regulations; unofficially, because of Ai’s outspoken criticism of the government. Months later, the artist was imprisoned for three months then placed under house arrest. When his passport was returned in 2015, he left the country and has not returned since.

“We live in a constantly changing landscape,” says Ai. His has certainly changed more than most people’s. After China, he set up in Berlin but left under a cloud, saying: “Nazism perfectly exists in German daily life today.” He moved on to the UK, where he has had run-ins with immigration authorities. On his first visit, he was initially granted a visa for just 20 days on account of his “criminal conviction” in China.

More here.

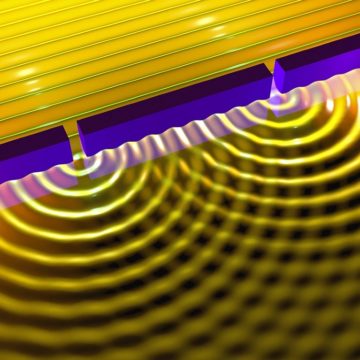

Light waves squeezed through ‘slits in time’

Davide Castelvecchi in Nature:

A celebrated experiment in 1801 showed that light passing through two thin slits interferes with itself, forming a characteristic striped pattern on the wall behind. Now, physicists have shown that a similar effect can arise with two slits in time rather than space: a single mirror that rapidly turns on and off causes interference in a laser pulse, making it change colour.

A celebrated experiment in 1801 showed that light passing through two thin slits interferes with itself, forming a characteristic striped pattern on the wall behind. Now, physicists have shown that a similar effect can arise with two slits in time rather than space: a single mirror that rapidly turns on and off causes interference in a laser pulse, making it change colour.

The result is reported on 3 April in Nature Physics1. It adds a new twist to the classic double-slit experiment performed by physicist Thomas Young, which demonstrated the wavelike aspect of light, but also — in its many later reincarnations — that quantum objects ranging from photons to molecules have a dual nature of both particle and wave.

More here.

Taj Muhammad & Shad Muhammad Niazi Qawwal: “Guniyan ke Maharaj Khusrau”

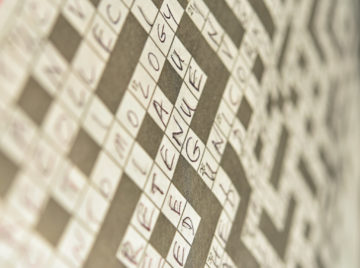

The Labor of Play

Benjamin Tausig at Public Books:

An Upper East Sider with advanced degrees playing Wordle over espresso; a suburban teenager pairing Call of Duty: Warzone with bong rips before work: both play, arguably, for the same reasons. Each delights in low-stakes release. Each enjoys the sense of completing a task (spelling words, killing enemies) that feels vaguely moral, and which the player might take pride in, even if virtually and for an audience composed only of themselves. What is different is only that the New York Times and other enlightened organs have now found ways to market trivial, dependence-inducing digital game products (already wildly lucrative in other settings) to the gentry. And the Times is hardly alone.

An Upper East Sider with advanced degrees playing Wordle over espresso; a suburban teenager pairing Call of Duty: Warzone with bong rips before work: both play, arguably, for the same reasons. Each delights in low-stakes release. Each enjoys the sense of completing a task (spelling words, killing enemies) that feels vaguely moral, and which the player might take pride in, even if virtually and for an audience composed only of themselves. What is different is only that the New York Times and other enlightened organs have now found ways to market trivial, dependence-inducing digital game products (already wildly lucrative in other settings) to the gentry. And the Times is hardly alone.

Is this boom in bourgeois gaming bad? The “inanity of many leisure activities” famously troubled the philosopher Theodor Adorno.

An ardent anti-capitalist—and a half-Jewish German refugee who feared that frivolous entertainment was a handmaiden to fascism (living in Los Angeles must have been interesting!)—Adorno had no problem with leisure, but he suspected that so-called free time had, in late capitalism, become little more than a recharging period between episodes of labor extraction, i.e., work days.

More here.

Bodies and Borders // Achille Mbembe

The Incredible Disappearing Doomsday

Kyle Paoletta at Harper’s Magazine:

The first signs that the mood was brightening among the corps of reporters called to cover one of the gravest threats humanity has ever faced appeared in the summer of 2021. “Climate change is not a pass/fail course,” Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post on August 9. “There is no chance that the world will avoid the effects of warming—we’re already experiencing them—but neither is there any point at which we are doomed.” Writing in the Guardian a few days later, Rebecca Solnit highlighted a paragraph from a recent report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that said carbon-dioxide removal technology could theoretically “reverse . . . some aspects of climate change.” Though she admitted this was “a long shot” that would require “heroic effort, unprecedented cooperation, and visionary commitment,” Solnit nevertheless concluded, “It is possible to do. And we know how to do it.”

The first signs that the mood was brightening among the corps of reporters called to cover one of the gravest threats humanity has ever faced appeared in the summer of 2021. “Climate change is not a pass/fail course,” Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post on August 9. “There is no chance that the world will avoid the effects of warming—we’re already experiencing them—but neither is there any point at which we are doomed.” Writing in the Guardian a few days later, Rebecca Solnit highlighted a paragraph from a recent report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that said carbon-dioxide removal technology could theoretically “reverse . . . some aspects of climate change.” Though she admitted this was “a long shot” that would require “heroic effort, unprecedented cooperation, and visionary commitment,” Solnit nevertheless concluded, “It is possible to do. And we know how to do it.”

In the following months, a new mode of environmental reporting bloomed: the age of climate optimism was upon us.

more here.

The Mind-Bending Fiction Of Mircea Cărtărescu

Will Self at The Nation:

This attempt to imbue his texts with greater realism by rejecting the reality of his own literary vocation has been part of Cărtărescu’s methodology since the dark days of Ceauşescu’s pseudo-communist regime. In earlier works, this denial had taken the form of the verbatim publishing of his own journals and the attendant claim that he doesn’t live his life but rather “constructed” it. But Cărtărescu also gives his novel a gritty sense of realism through its setting as well as its bitter views of its protagonist. The Bucharest of Solenoid has the curious air of a building constructed according to Hitler and Albert Speer’s Theorie vom Ruinwert: namely with the aim of having it look better as it ages than when new-made. For decay is everywhere in the Bucharest of the counter-Cărtărescu. His city is an urban environment seemingly purpose-built to express impermanence and decay, one in which moldering old mercantile houses and newly built yet already decaying apartment buildings are rendered phantasmagorical by the nameless narrator’s wanderings through their chipped and spalling chambers. Repeatedly and elegiacally, the counter-Cărtărescu hymns the city of his birth as “the saddest city,” and just as the precision of his writing imbues a dream with great realism, so too does the crumbling nature of his hometown offer us fragments of material beauty—perhaps the very ones necessary to shore us up against our current ruination.

This attempt to imbue his texts with greater realism by rejecting the reality of his own literary vocation has been part of Cărtărescu’s methodology since the dark days of Ceauşescu’s pseudo-communist regime. In earlier works, this denial had taken the form of the verbatim publishing of his own journals and the attendant claim that he doesn’t live his life but rather “constructed” it. But Cărtărescu also gives his novel a gritty sense of realism through its setting as well as its bitter views of its protagonist. The Bucharest of Solenoid has the curious air of a building constructed according to Hitler and Albert Speer’s Theorie vom Ruinwert: namely with the aim of having it look better as it ages than when new-made. For decay is everywhere in the Bucharest of the counter-Cărtărescu. His city is an urban environment seemingly purpose-built to express impermanence and decay, one in which moldering old mercantile houses and newly built yet already decaying apartment buildings are rendered phantasmagorical by the nameless narrator’s wanderings through their chipped and spalling chambers. Repeatedly and elegiacally, the counter-Cărtărescu hymns the city of his birth as “the saddest city,” and just as the precision of his writing imbues a dream with great realism, so too does the crumbling nature of his hometown offer us fragments of material beauty—perhaps the very ones necessary to shore us up against our current ruination.

more here.

Life Evolves. Can Attempts to Create ‘Artificial Life’ Evolve, Too?

Shi En Kim in Scientific American:

What is life? Like most great questions, this one is easy to ask but difficult to answer. Scientists have been trying for centuries, and philosophers have done so for millennia. Today our knowledge is so advanced that we can precisely manipulate life’s building blocks—DNA, RNA and proteins—to build biological machines and engineer new genomes. Yet despite all we know, no universal consensus currently exists on life’s fundamental definition.

What is life? Like most great questions, this one is easy to ask but difficult to answer. Scientists have been trying for centuries, and philosophers have done so for millennia. Today our knowledge is so advanced that we can precisely manipulate life’s building blocks—DNA, RNA and proteins—to build biological machines and engineer new genomes. Yet despite all we know, no universal consensus currently exists on life’s fundamental definition.

The reason life’s definition still eludes us is simple: we know of just one type of life—the kind that exists on Earth—and it’s challenging to do science with a sample size of one. This is the so-called N = 1 problem (wherein “N” denotes the number of eligible candidates that scientists can study). No matter how ingenious researchers may be in divining life’s general principles from the single instance of which they’re sure, they have no way of confirming whether they’ve done so successfully until N increases. Searching for another instance of life—whether it’s found right here on Earth, elsewhere in the solar system or beyond—is one way to expand N. The search has scarcely begun, but it has already consumed billions of dollars and countless hours of labor, even though there is no guarantee that a discovery will ever come.

More here.

The Wondrous Connections Between Mathematics and Literature

Sarah Hart in The New York Times:

“Call me Ishmael.” This has to be one of the most famous opening sentences in all of literature, and I’m embarrassed to say that — until quite recently — I didn’t get beyond it. “Moby-Dick” was, for me, one of those books that languished in the guilt-inducing category of “things you should have read a long time ago,” and I just never got around to it. Plus, I am a mathematician. And despite my interest in literature, my intellectual priorities did not include 400-page novels about whales — or so I thought. That all changed one day when I overheard a mathematician friend mention that “Moby-Dick” contains a reference to cycloids.

“Call me Ishmael.” This has to be one of the most famous opening sentences in all of literature, and I’m embarrassed to say that — until quite recently — I didn’t get beyond it. “Moby-Dick” was, for me, one of those books that languished in the guilt-inducing category of “things you should have read a long time ago,” and I just never got around to it. Plus, I am a mathematician. And despite my interest in literature, my intellectual priorities did not include 400-page novels about whales — or so I thought. That all changed one day when I overheard a mathematician friend mention that “Moby-Dick” contains a reference to cycloids.

Cycloids are among the most beautiful mathematical curves in existence — the French mathematician Blaise Pascal found them so distractingly fascinating that he claimed merely thinking about them could relieve the pain of a bad toothache — but applications to whaling are not usually listed on their résumé. Intrigued, I finally read “Moby-Dick,” and was delighted to find that it abounds with mathematical metaphors. I realized further it’s not just Herman Melville; Leo Tolstoy writes about calculus, James Joyce about geometry. Fractal structure underlies Michael Crichton’s “Jurassic Park” and algebraic principles govern various forms of poetry. We mathematicians even appear in work by authors as disparate as Arthur Conan Doyle and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

There have been occasional academic studies on mathematical aspects of specific genres and authors. But the more holistic connections between mathematics and literature have not received the attention they deserve.

More here.

Friday Poem

Clever and Poor

She has always been clever and poor,

Especially here off the Yugoslav

Train on the platform of dust. Clever was

Her breakfast of nutmeg ground in water

In place of rationed tea. Poor was the cracked

Cup, the missing bread. Clever are the six

Handkerchiefs stitched to the size of a scarf

And knotted at her throat. Poor the thin

Coat, patched with cloth from the pockets

She then sewed shut. Clever is the lipstick,

Petunia pink, she rubbed with a rag on her nails.

Poor the nails, yellow with cold, Posed

In a cape to hide her waist, her photograph

Was clever. Poor then was what she called

The last bill twisted in her wallet. Letter

After letter she was clever and more

Clever, for months she wrote a newspaperman

Who liked her in the picture. The poor

Saved pounds of sugar, she traded them

For stamps. He wanted a clever wife. She was poor

So he sent a ticket—now she would come to her wedding

By train. Poor, the baby left with the nuns.

Because she is clever, on the platform to meet him

She thinks, Be generous with you eyes. What is poor

Is what she sees. Cracks stop the station clock,

Girls with candle grease to sell. Clever, poor,

Clever and poor, her husband, more nervous

Than his picture, his shined shoes tied with twine.

by Penelope Pelizzon

from Ploughshares. Everyday Seductions

Spring, 1995

Thursday, April 6, 2023

The Roots, Explained with a Single Chord

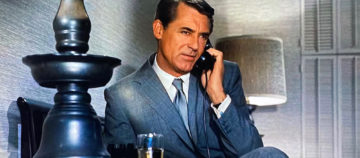

The Real Star of North by Northwest is Cary Grant’s Suit

Todd McEwen at Lit Hub:

North by Northwest isn’t about what happens to Cary Grant, it’s about what happens to his suit. The suit has the adventures, a gorgeous New York suit threading its way through America. The title sequence in which the stark lines of a Madison Avenue office building are “woven” together could be the construction of Cary in his suit right there—he gets knitted into his suit before his adventure can begin.

North by Northwest isn’t about what happens to Cary Grant, it’s about what happens to his suit. The suit has the adventures, a gorgeous New York suit threading its way through America. The title sequence in which the stark lines of a Madison Avenue office building are “woven” together could be the construction of Cary in his suit right there—he gets knitted into his suit before his adventure can begin.

Indeed some of the popular “suitings” of that time, “windowpane” or “glen plaid,” reflected, even perfectly complemented office buildings. Cary’s suit reflects New York, identifies him as a thrusting exec, but also protects him, what else is a suit for? Reflects and Protects … a slogan Roger Thornhill himself might have come up with. The recent usage of calling a guy a “suit” if you don’t like him, consider him a flunky or a waste of space, applies to Cary at the beginning of the film: this suit comes barreling out of the elevator, yammering business trivialities at a mile a minute, with the energy of the entire building.

more here.

Writing As Suicide And Vice Versa

Ben Hutchinson at Literary Review:

On 28 February 1989, a matter of days after the publication of what he had described as the first volume of a tetralogy, the Swiss writer Hermann Burger kept a long-held promise and killed himself. The world could not say it had not been warned: from his first novel, Schilten (1976), about a school teacher who prepares his pupils for death, to his collection of aphorisms Tractatus logico-suicidalis (1988), a gathering of over a thousand ‘mortologisms’ on the logic of self-slaughter, Burger was nothing if not consistently morbid. To rehearse Spike Milligan’s famous epitaph, he had told us he was ill.

On 28 February 1989, a matter of days after the publication of what he had described as the first volume of a tetralogy, the Swiss writer Hermann Burger kept a long-held promise and killed himself. The world could not say it had not been warned: from his first novel, Schilten (1976), about a school teacher who prepares his pupils for death, to his collection of aphorisms Tractatus logico-suicidalis (1988), a gathering of over a thousand ‘mortologisms’ on the logic of self-slaughter, Burger was nothing if not consistently morbid. To rehearse Spike Milligan’s famous epitaph, he had told us he was ill.

That Burger’s warnings were not taken seriously during his lifetime owes much to his consistently difficult, narcissistic character. Declaring that he had no need to save money given his intention to die young, Burger drove around in a Ferrari, wore expensive white suits, performed magic tricks for politicians and offended almost everyone with whom he came into contact.

more here.

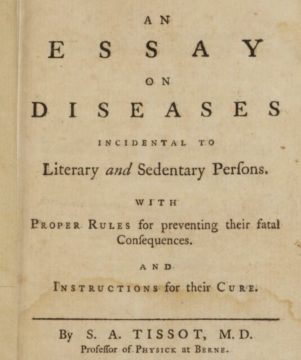

An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons

Hunter Dukes in The Public Domain Review:

It was dangerous to be a man of letters in the eighteenth century. All that rumination; such single-minded concentration; countless hours hunched over the escritoire. “Some men are by nature insatiable in drinking wine, others are born cormorants of books”, wrote the Swiss physician Samuel-Auguste Tissot in An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons (1768). As with the reckless consumer of claret, an overindulgence in books could have devastating consequences for the mind and body.

It was dangerous to be a man of letters in the eighteenth century. All that rumination; such single-minded concentration; countless hours hunched over the escritoire. “Some men are by nature insatiable in drinking wine, others are born cormorants of books”, wrote the Swiss physician Samuel-Auguste Tissot in An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Literary and Sedentary Persons (1768). As with the reckless consumer of claret, an overindulgence in books could have devastating consequences for the mind and body.

Across his essay, Tissot offers hundreds of examples of men who read too much, studied too hard, and consumed knowledge to the point of madness. There is the young man who developed an allergy to reading: “if he read even a few pages, he was torn with convulsions of the muscles of the head and face, which assumed the appearance of ropes stretched very tight.” And the man whose laser focus effected hair removal: “his beard fell first, then his eye-lashes, then his eye-brows, then the hair on his head, and finally all the hairs of his body”. There is Nicolas Malebranche, who was gripped with “dreadful palpitations” upon looking into Descartes’ Treatise on Man, and an unnamed Parisian rhetorician, who “fainted away whilst he was perusing some of the sublime passages of Homer.”

More here.