Kerri Greenidge in The New York Times:

It’s a testament to Black endurance and brilliance that the little girl called Phillis Wheatley became, within 12 years of her arrival in Boston, the most significant African American poet of the 18th century. Yet, as the historian David Waldstreicher shows in “The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley,” his thoroughly researched, beautifully rendered and cogently argued biography, Wheatley is brilliant not merely because she survived and composed some of the most important works of trans-Atlantic literature. Rather, Waldstreicher insists, Wheatley was a supremely gifted neoclassical practitioner of language, an “organic intellectual of the enslaved.”

It’s a testament to Black endurance and brilliance that the little girl called Phillis Wheatley became, within 12 years of her arrival in Boston, the most significant African American poet of the 18th century. Yet, as the historian David Waldstreicher shows in “The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley,” his thoroughly researched, beautifully rendered and cogently argued biography, Wheatley is brilliant not merely because she survived and composed some of the most important works of trans-Atlantic literature. Rather, Waldstreicher insists, Wheatley was a supremely gifted neoclassical practitioner of language, an “organic intellectual of the enslaved.”

…Waldstreicher asks us to appreciate the sarcasm in Wheatley’s lines. He suggests that she was well acquainted with a trans-Atlantic Methodism that deemed an “abominable hypocrisy” the widely accepted notion of the slave trade as a path for Africans to salvation. In her poem, Wheatley doesn’t reinforce the notion of African inferiority; she challenges it. This is apparent in the final two couplets: “Some view our sable race with scornful eye,/‘Their colour is a diabolic die.’/Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,/May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” These couplets, Waldstreicher argues, are “the real point, set up by the first four lines that seem to bathe enslavement in evangelical glory, something white folks might want to believe.”

In portraying Wheatley as an often subversive artist who understands and talks back to the racial assumptions of her time, Waldstreicher refuses to take the white Wheatleys at their word.

More here.

John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson were unlikely allies in the war to preserve

John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson were unlikely allies in the war to preserve  “I am human, and consider nothing human alien to me”: The famous line from the Roman playwright Terence, written more than two millenniums ago, is easy to assert but hard to live by, at least with any consistency. The attitude it suggests is adamantly open-minded and resolutely pluralist: Even the most annoying, the most confounding, the most atrocious example of anyone’s behavior is necessarily part of the human experience. There are points of connection between all of us weirdos, no matter how different we are. Michel de Montaigne liked the line so much that he had the Latin original — Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto — inscribed on a ceiling joist in his library.

“I am human, and consider nothing human alien to me”: The famous line from the Roman playwright Terence, written more than two millenniums ago, is easy to assert but hard to live by, at least with any consistency. The attitude it suggests is adamantly open-minded and resolutely pluralist: Even the most annoying, the most confounding, the most atrocious example of anyone’s behavior is necessarily part of the human experience. There are points of connection between all of us weirdos, no matter how different we are. Michel de Montaigne liked the line so much that he had the Latin original — Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto — inscribed on a ceiling joist in his library. Guiyang didn’t have many restaurants, per se. The metropolis was more of a city-wide night market. Even in the pre-COVID days, streets like Qingyun Road were only half-filled with cars, to leave room for tents and tables that stretched to the horizon, and for smoke and steam that rose into the clouds. Eateries didn’t burden you with 14-page menus, common at Shanghainese or Northeastern restaurants. No — a làoguō 烙锅 shop sold laoguo (think Korean BBQ with more vegetables, cooked over a clay pot dome). A sīwáwa 丝娃娃 shop sold siwawa (shreds of 20-plus varieties of fresh and pickled vegetables that you roll into a thin, rice cake-like taco). And tofu stands sold tofu. But probably not the tofu you’re thinking of.

Guiyang didn’t have many restaurants, per se. The metropolis was more of a city-wide night market. Even in the pre-COVID days, streets like Qingyun Road were only half-filled with cars, to leave room for tents and tables that stretched to the horizon, and for smoke and steam that rose into the clouds. Eateries didn’t burden you with 14-page menus, common at Shanghainese or Northeastern restaurants. No — a làoguō 烙锅 shop sold laoguo (think Korean BBQ with more vegetables, cooked over a clay pot dome). A sīwáwa 丝娃娃 shop sold siwawa (shreds of 20-plus varieties of fresh and pickled vegetables that you roll into a thin, rice cake-like taco). And tofu stands sold tofu. But probably not the tofu you’re thinking of. There’s now an

There’s now an  Just before Christmas, federal health officials confirmed

Just before Christmas, federal health officials confirmed  I’ve found myself thinking a lot about that epigraph in the wake of two back-to-back events this past October. One was Soulages’s death at age 102, the other a visit to the monographic room recently devoted to Pierrette Bloch (1928–2017) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (MAM). Comprising eight objects from between 1974 and 1999, all belonging to the museum’s permanent collection, the focused presentation offered a welcome opportunity to think broadly about a singularly poetic body of work exhibited regularly in Europe but rarely in the US. Particularly in the wake of Soulages’s death, however, it also invites fresh consideration of the two artists’ longtime dialogue. Introduced in 1949 by Bloch’s art professor Henri Goetz, the pair were friends for nearly seven decades, and their lives and oeuvres were closely intertwined. Early in her career, Bloch used a spare room in Soulages’s house as her studio, and each collected work by the other. Slightly older than the artists of Supports/Surfaces but avowedly attentive to their investigations, Bloch developed a similarly expanded practice of painting, moving beyond the stretched canvas support to engage a broad array of nontraditional and often notably humble materials. Her work brilliantly illuminates both the fecundity and the limits of the “materiological” Soulages brought to the fore through Segalen’s striking image of signs woven in stone.

I’ve found myself thinking a lot about that epigraph in the wake of two back-to-back events this past October. One was Soulages’s death at age 102, the other a visit to the monographic room recently devoted to Pierrette Bloch (1928–2017) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (MAM). Comprising eight objects from between 1974 and 1999, all belonging to the museum’s permanent collection, the focused presentation offered a welcome opportunity to think broadly about a singularly poetic body of work exhibited regularly in Europe but rarely in the US. Particularly in the wake of Soulages’s death, however, it also invites fresh consideration of the two artists’ longtime dialogue. Introduced in 1949 by Bloch’s art professor Henri Goetz, the pair were friends for nearly seven decades, and their lives and oeuvres were closely intertwined. Early in her career, Bloch used a spare room in Soulages’s house as her studio, and each collected work by the other. Slightly older than the artists of Supports/Surfaces but avowedly attentive to their investigations, Bloch developed a similarly expanded practice of painting, moving beyond the stretched canvas support to engage a broad array of nontraditional and often notably humble materials. Her work brilliantly illuminates both the fecundity and the limits of the “materiological” Soulages brought to the fore through Segalen’s striking image of signs woven in stone. If there is one part of one building that is quintessential Christopher Wren it is not the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, or the ceremonial river frontage of the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich, nor even any of the infinitely various steeples of his city churches, but the base of the Monument.

If there is one part of one building that is quintessential Christopher Wren it is not the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, or the ceremonial river frontage of the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich, nor even any of the infinitely various steeples of his city churches, but the base of the Monument. The

The

Around noon on March 9, I learned that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had shut down the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), where my company has some of its accounts. My co-founder and I were in the middle of a call with some of our advisors, all experienced hands in the tech startup world actively advising and investing in tech startups like ours. The Zoom room was empty within seconds. We all immediately knew what that meant: The cash we pay our employees and vendors was now locked up—perhaps indefinitely.

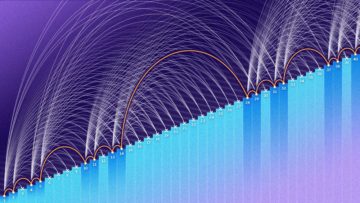

Around noon on March 9, I learned that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had shut down the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), where my company has some of its accounts. My co-founder and I were in the middle of a call with some of our advisors, all experienced hands in the tech startup world actively advising and investing in tech startups like ours. The Zoom room was empty within seconds. We all immediately knew what that meant: The cash we pay our employees and vendors was now locked up—perhaps indefinitely. On Sunday, February 5, Olof Sisask and Thomas Bloom received an email containing a stunning breakthrough on the biggest unsolved problem in their field. Zander Kelley, a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, had sent Sisask and Bloom

On Sunday, February 5, Olof Sisask and Thomas Bloom received an email containing a stunning breakthrough on the biggest unsolved problem in their field. Zander Kelley, a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, had sent Sisask and Bloom  Dante Alighieri’s

Dante Alighieri’s  As

As