Category: Recommended Reading

A.I. Wrote the Book

Dwight Garner at the NY Times:

Now comes a new novella, “Death of an Author,” a murder mystery published under the pseudonym Aidan Marchine. It’s the work of the novelist and journalist Stephen Marche, who coaxed the story from three programs, ChatGPT, Sudowrite and Cohere, using a variety of prompts. The book’s language, he says, is 95 percent machine-generated, somewhat like the food at a Ruby Tuesday.

Now comes a new novella, “Death of an Author,” a murder mystery published under the pseudonym Aidan Marchine. It’s the work of the novelist and journalist Stephen Marche, who coaxed the story from three programs, ChatGPT, Sudowrite and Cohere, using a variety of prompts. The book’s language, he says, is 95 percent machine-generated, somewhat like the food at a Ruby Tuesday.

Well, somebody was going to do it. In truth, other hustlers out there on Amazon already have. But “Death of an Author” is arguably the first halfway readable A.I. novel, an early glimpse at what is vectoring toward readers. It has been presided over by a literate writer who has pushed the borg in twisty directions. He got it to spit out more than boilerplate, some of the time. If you squint, you can convince yourself you’re reading a real novel.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Seven in the Woods

Am I as old as I am?

Maybe not. Time is a mystery

that can tip us upside down.

Yesterday I was seven in the woods,

a bandage covering my blind eye,

in a bedroll Mother made me

so I could sleep out in the woods

far from people. A garter snake glided by

without noticing me. A chickadee

landed on my bare toe, so light

she wasn’t believable. The night

had been long and the treetops

thick with a trillion stars. Who

was I, half-blind on the forest floor

who was I at age seven? Sixty-eight

years later I can still inhabit that boy’s

body without thinking of the time between.

It is the burden of life to be many ages

without seeing the end of time.

by Jim Harrison

Friday, May 5, 2023

Snoop Dogg on AI risk: “Sh–, what the f—?”

Benj Edwards in Ars Technica:

During his response, Snoop described how conversing with a large language model (such as ChatGPT or Bing Chat) reminds him of sci-fi movies he watched as a kid. Showing that he keeps up with current events, Snoop also referenced Geoffery Hinton, who resigned this week from Google so he could speak of the dangers of AI without conflicts of interest:

During his response, Snoop described how conversing with a large language model (such as ChatGPT or Bing Chat) reminds him of sci-fi movies he watched as a kid. Showing that he keeps up with current events, Snoop also referenced Geoffery Hinton, who resigned this week from Google so he could speak of the dangers of AI without conflicts of interest:

Well I got a motherf*cking AI right now that they did made for me. This n***** could talk to me. I’m like, man this thing can hold a real conversation? Like real for real? Like it’s blowing my mind because I watched movies on this as a kid years ago. When I see this sh*t I’m like what is going on? And I heard the dude, the old dude that created AI saying, “This is not safe, ’cause the AIs got their own minds, and these motherf*ckers gonna start doing their own sh*t. I’m like, are we in a f*cking movie right now, or what? The f*ck man? So do I need to invest in AI so I can have one with me? Or like, do y’all know? Sh*t, what the f*ck?” I’m lost, I don’t know.

More here.

Tragedy & farce in climate commentary

Ingo Venzke in the European Review of Books:

The phrase « it’s not too late », for me, brings an artificial smile. I stumble onto it as I walk into a bookstore and see the flashy Carbon Almanac (2022) promoted at the entrance, one of many such books to appear in the last, late year. It shouts from the cover: « It’s not too late. » The foreword was written by Seth Godin, a marketing guru out of the dot-com avantgarde. What will save us is « the hope that comes from realizing that it’s not too late. » The refrain is a staple of the genre. Another entry, a new report from the Club of Rome entitled Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, offers a kindred burst of optimism about the future against the backdrop of a bleak present. Greater planetary health and social well-being are within reach. The authors will « show you that this is indeed fully possible ». Meanwhile the heavy-weight United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released two punchy reports of its own in 2022. They hammered the message that countries’ pledges to cut emissions fall far below climate change targets, and that the impact of climate change is already devastating for many parts of humanity, the ecosystem, and for the biodiversity that now suffers a mass extinction.

The phrase « it’s not too late », for me, brings an artificial smile. I stumble onto it as I walk into a bookstore and see the flashy Carbon Almanac (2022) promoted at the entrance, one of many such books to appear in the last, late year. It shouts from the cover: « It’s not too late. » The foreword was written by Seth Godin, a marketing guru out of the dot-com avantgarde. What will save us is « the hope that comes from realizing that it’s not too late. » The refrain is a staple of the genre. Another entry, a new report from the Club of Rome entitled Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, offers a kindred burst of optimism about the future against the backdrop of a bleak present. Greater planetary health and social well-being are within reach. The authors will « show you that this is indeed fully possible ». Meanwhile the heavy-weight United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released two punchy reports of its own in 2022. They hammered the message that countries’ pledges to cut emissions fall far below climate change targets, and that the impact of climate change is already devastating for many parts of humanity, the ecosystem, and for the biodiversity that now suffers a mass extinction.

Earth for All may have drowned in the sea of climate commentary. But it is worth reading, for what it is, and what it is not.

More here.

Can you guess the Beatles song from the drum part?

Sri Lanka debt deal shows creditors can set aside geopolitical rivalries for debt-distressed nations

Ram Manikkalingam in SCMP:

The International Monetary Fund approved a US$3 billion loan to Sri Lanka a month ago as the first step in restructuring its debt. This is a significant victory for Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe and could lead to a gradual stabilisation of the economy and the government’s turnaround from bankruptcy.

The International Monetary Fund approved a US$3 billion loan to Sri Lanka a month ago as the first step in restructuring its debt. This is a significant victory for Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe and could lead to a gradual stabilisation of the economy and the government’s turnaround from bankruptcy.

After the “staff-level agreement” signed with the IMF six months ago, Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring has finally been approved by the IMF board. In this restructuring, China played a major role. As Sri Lanka’s (and the world’s) largest sovereign creditor, China joined Western governments and India in providing the assurances that unlocked the financing.

But is China’s role in Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring a one-off or a signal that China’s position on sovereign debt has shifted – something that could lead to a global policy breakthrough in negotiating debt restructuring?

More here.

How Philosophy Got Lost

Fusion And The Holy Grail

Tristan Abbey at The New Atlantis:

A little history never hurt anybody. We can start the clock in 1920. In February of that year, the journal Nature reported the results of an experiment conducted by a British scientist named Francis William Aston. A future Nobel laureate, Aston’s job at the famous Cavendish Laboratory was to estimate the masses of chemical elements. At the time, it was believed that a single helium atom comprised four hydrogen atoms, suggesting that the mass of a single hydrogen should be exactly one-fourth the mass of a helium. Aston determined this was not, in fact, the case. Hydrogen atoms were just a smidge heavier than they should have been. When four hydrogen atoms fused into a helium, where did the extra mass go?

A little history never hurt anybody. We can start the clock in 1920. In February of that year, the journal Nature reported the results of an experiment conducted by a British scientist named Francis William Aston. A future Nobel laureate, Aston’s job at the famous Cavendish Laboratory was to estimate the masses of chemical elements. At the time, it was believed that a single helium atom comprised four hydrogen atoms, suggesting that the mass of a single hydrogen should be exactly one-fourth the mass of a helium. Aston determined this was not, in fact, the case. Hydrogen atoms were just a smidge heavier than they should have been. When four hydrogen atoms fused into a helium, where did the extra mass go?

Enter Arthur Eddington, a British scientist who served essentially (but not merely) as Albert Einstein’s chief popularizer. In August of that year, Eddington delivered a lecture in which he described how stars in outer space were “drawing on some vast reservoir of energy by means unknown to us.”

more here.

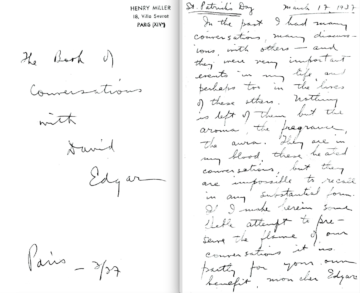

A Letter from Henry Miller

Henry Miller at The Paris Review:

So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God is schizophrenic,” as you so aptly said, only because the mind, whetted to acute understanding by the continuous confrontation of oscillations, finally envisages a resolution of conflict in a necessitous freedom of action in which significance and expression are one. Which is madness, or, if you like, only schizophrenia. The word schizophrenia, to put it better, contains a minimum and a maximum of relation to the thing it defines. It is a counter to sound with …

So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God is schizophrenic,” as you so aptly said, only because the mind, whetted to acute understanding by the continuous confrontation of oscillations, finally envisages a resolution of conflict in a necessitous freedom of action in which significance and expression are one. Which is madness, or, if you like, only schizophrenia. The word schizophrenia, to put it better, contains a minimum and a maximum of relation to the thing it defines. It is a counter to sound with …

more here.

Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey?

Ted Chiang in The New Yorker:

When we talk about artificial intelligence, we rely on metaphor, as we always do when dealing with something new and unfamiliar. Metaphors are, by their nature, imperfect, but we still need to choose them carefully, because bad ones can lead us astray. For example, it’s become very common to compare powerful A.I.s to genies in fairy tales. The metaphor is meant to highlight the difficulty of making powerful entities obey your commands; the computer scientist Stuart Russell has cited the parable of King Midas, who demanded that everything he touched turn into gold, to illustrate the dangers of an A.I. doing what you tell it to do instead of what you want it to do. There are multiple problems with this metaphor, but one of them is that it derives the wrong lessons from the tale to which it refers. The point of the Midas parable is that greed will destroy you, and that the pursuit of wealth will cost you everything that is truly important. If your reading of the parable is that, when you are granted a wish by the gods, you should phrase your wish very, very carefully, then you have missed the point.

When we talk about artificial intelligence, we rely on metaphor, as we always do when dealing with something new and unfamiliar. Metaphors are, by their nature, imperfect, but we still need to choose them carefully, because bad ones can lead us astray. For example, it’s become very common to compare powerful A.I.s to genies in fairy tales. The metaphor is meant to highlight the difficulty of making powerful entities obey your commands; the computer scientist Stuart Russell has cited the parable of King Midas, who demanded that everything he touched turn into gold, to illustrate the dangers of an A.I. doing what you tell it to do instead of what you want it to do. There are multiple problems with this metaphor, but one of them is that it derives the wrong lessons from the tale to which it refers. The point of the Midas parable is that greed will destroy you, and that the pursuit of wealth will cost you everything that is truly important. If your reading of the parable is that, when you are granted a wish by the gods, you should phrase your wish very, very carefully, then you have missed the point.

So, I would like to propose another metaphor for the risks of artificial intelligence. I suggest that we think about A.I. as a management-consulting firm, along the lines of McKinsey & Company. Firms like McKinsey are hired for a wide variety of reasons, and A.I. systems are used for many reasons, too. But the similarities between McKinsey—a consulting firm that works with ninety per cent of the Fortune 100—and A.I. are also clear. Social-media companies use machine learning to keep users glued to their feeds. In a similar way, Purdue Pharma used McKinsey to figure out how to “turbocharge” sales of OxyContin during the opioid epidemic. Just as A.I. promises to offer managers a cheap replacement for human workers, so McKinsey and similar firms helped normalize the practice of mass layoffs as a way of increasing stock prices and executive compensation, contributing to the destruction of the middle class in America.

More here.

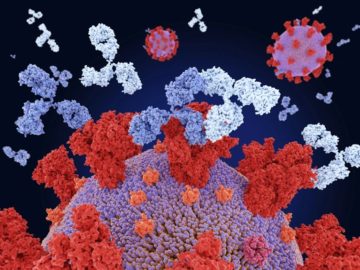

How generative AI is building better antibodies

Ewen Callaway in Nature:

Antibodies are among the immune system’s key weapons against infection. The proteins have become a darling of the biotechnology industry, in part because they can be engineered to attach to almost any protein imaginable to manipulate its activity. But generating antibodies with useful properties and improving on these involves “a lot of brute-force screening”, says Brian Hie, a computational biologist at Stanford who also co-led the study.

Antibodies are among the immune system’s key weapons against infection. The proteins have become a darling of the biotechnology industry, in part because they can be engineered to attach to almost any protein imaginable to manipulate its activity. But generating antibodies with useful properties and improving on these involves “a lot of brute-force screening”, says Brian Hie, a computational biologist at Stanford who also co-led the study.

To see whether generative AI tools could cut out some of the grunt work, Hie, Kim and their colleagues used neural networks called protein language models. These are similar to the ‘large language models’ that form the basis of tools such as ChatGPT. But instead of being fed vast volumes of text, protein language models are trained on tens of millions of protein sequences. Other researchers have used such models to design completely new proteins, and to help predict the structure of proteins with high accuracy. Hie’s team used a protein language model — developed by researchers at Meta AI, a part of tech giant Meta based in New York City, — to suggest a small number of mutations for antibodies. The model was trained on only a few thousand antibody sequences, out of the nearly 100 million protein sequences it learned from. Despite this, a surprisingly high proportion of the models’ suggestions boosted the ability of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, ebolavirus and influenza to bind to their targets.

More here.

Friday Poem

Plea to a Particular Soft-handed Goddess

Where there are no streets

the world is less remembered

and hypotheses are lean and scattered.

I kneel before a pine tree standing;

listen to the locust-singing of my soul;

hope for a brimful of some sort.

I pray for raindrop ablution;

for embodiment of sandhill dreams;

for a scheme to end

this bughouse commotion;

these spasms of faddism.

The question is:

How to work out a pardonable truce

between one’s honest opinion

and the official attitude.

What I really want is for you

to come and stand beside me

and probe with pagan tenderness

Beyond my bone-weight

until you find a forgotten disclosure

like the surprise of my being.

by Parm Mayer

from Heartland, Poets of the Midwest

Northern Illinois University Press, 1967

Thursday, May 4, 2023

How Your Internal Compass Works

Matt Hrodey in Discover Magazine:

In a lab mouse version of The Truman Show, researchers from Harvard Medical School constructed a little world for a new paper. An eight-inch-wide platform raised 20 inches off the ground stood at the center, covered in mouse bedding. All around curved a tall LED screen, blank until a white, disorienting stripe flashed to one side or the other. The researchers were looking for head direction cells in the mouse, which act as an inner compass in the brains of humans, insects, animals and fish. While not a proper magnetic compass, this neural compass acts as a relative one based on landmarks instead of Earth’s magnetic field. In humans, it spans several different brain areas, including the anterodorsal thalamus, the area targeted in the mouse study.

In a lab mouse version of The Truman Show, researchers from Harvard Medical School constructed a little world for a new paper. An eight-inch-wide platform raised 20 inches off the ground stood at the center, covered in mouse bedding. All around curved a tall LED screen, blank until a white, disorienting stripe flashed to one side or the other. The researchers were looking for head direction cells in the mouse, which act as an inner compass in the brains of humans, insects, animals and fish. While not a proper magnetic compass, this neural compass acts as a relative one based on landmarks instead of Earth’s magnetic field. In humans, it spans several different brain areas, including the anterodorsal thalamus, the area targeted in the mouse study.

All neural compasses include brain cells with preferred firing directions, meaning they fire continuously and spew neurotransmitters when the head is pointed in a certain direction. But how do they know when that’s happening?

More here.

The Experience Machine – how our brains really work

Steven Poole in The Guardian:

Do we see the world directly, or do we make some of it up? It was the great 19th-century scientist Hermann von Helmholtz who first argued that some unconscious process of logical reasoning must be inherent in optical and auditory perception. That insight was rediscovered in the late 20th century, leading to the modern consensus of cognitive science: we think we see and hear the outside world directly, but most of our experience is created by the brain, meaning its best guesses are based on limited information as to what might really be out there. In other words, we are constantly filling in gaps with predictions.

Do we see the world directly, or do we make some of it up? It was the great 19th-century scientist Hermann von Helmholtz who first argued that some unconscious process of logical reasoning must be inherent in optical and auditory perception. That insight was rediscovered in the late 20th century, leading to the modern consensus of cognitive science: we think we see and hear the outside world directly, but most of our experience is created by the brain, meaning its best guesses are based on limited information as to what might really be out there. In other words, we are constantly filling in gaps with predictions.

The Sussex-based cognitive philosopher Andy Clark provides an engaging overview of what he slightly over-claims to be this “new theory” of predictive processing. It is demonstrated in enjoyable and surprising ways: for example, by “Mooney images”, which at first look like random monochrome noise, until you are shown a more detailed second version; you can then “see” (and can’t unsee) the real image in the original. Your predictions have now been updated to be more accurate. People, it turns out, can also be primed to hallucinate Bing Crosby singing White Christmas while listening to pure white noise.

More here.

Love Ruins Everything: On Claire Dederer’s ‘Monsters’

Sophia Stewart at The Millions:

Recently, a friend and I went to a screening of one of our favorite movies, Moonstruck, followed by a conversation with the screenwriter, now in his early seventies. Onstage he was quick-witted and charming, just the kind of person I’d expected to pen such a smart, savory love story. Afterward, as we headed home on the packed subway, I mentioned to my friend that I’d found the screenwriter to be very handsome. She agreed. We wondered aloud if he had grown into his good looks or if he’d always possessed them. Then we took to Google for the answer.

Recently, a friend and I went to a screening of one of our favorite movies, Moonstruck, followed by a conversation with the screenwriter, now in his early seventies. Onstage he was quick-witted and charming, just the kind of person I’d expected to pen such a smart, savory love story. Afterward, as we headed home on the packed subway, I mentioned to my friend that I’d found the screenwriter to be very handsome. She agreed. We wondered aloud if he had grown into his good looks or if he’d always possessed them. Then we took to Google for the answer.

Holding my phone between us, I swiped through images of him on various red carpets, clutching an Oscar, clutching a Tony, clutching the waist of a blonde actress. My next swipe summoned the headline of a 2012 Daily Mail article, announcing that the screenwriter had been “hit with a $5m lawsuit by 26-year-old who claims he choked her with a belt during rough sex.” We groaned in unison and dutifully read on. In the article, the woman describes multiple “violent encounters” with the screenwriter, alleging that he had laughed when she said he was hurting her during sex, and then complained about her blood staining his sheets.

More here.

Geoffrey Hinton tells us why he’s now scared of the tech he helped build

Will Douglas Heaven in the MIT Technology Review:

Does Hinton really think he can get enough people in power to share his concerns? He doesn’t know. A few weeks ago, he watched the movie Don’t Look Up, in which an asteroid zips toward Earth, nobody can agree what to do about it, and everyone dies—an allegory for how the world is failing to address climate change.

“I think it’s like that with AI,” he says, and with other big intractable problems as well. “The US can’t even agree to keep assault rifles out of the hands of teenage boys,” he says.

Hinton’s argument is sobering. I share his bleak assessment of people’s collective inability to act when faced with serious threats. It is also true that AI risks causing real harm—upending the job market, entrenching inequality, worsening sexism and racism, and more. We need to focus on those problems. But I still can’t make the jump from large language models to robot overlords. Perhaps I’m an optimist.

When Hinton saw me out, the spring day had turned gray and wet. “Enjoy yourself, because you may not have long left,” he said. He chuckled and shut the door.

More here.

Democrats Must Renew Their Allegiance to the Working Class

Seth Moskowitz in Persuasion:

Democrats were once the party of the working class. From the New Deal era through the mid-1960s, clear majorities of working-class whites and black voters of all economic strata threw their support behind Democrats.

Democrats were once the party of the working class. From the New Deal era through the mid-1960s, clear majorities of working-class whites and black voters of all economic strata threw their support behind Democrats.

But the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 marked the end of that tenuous cross-racial coalition. Furious and full of racial resentment, white working-class voters fled the Democratic Party into the open arms of Richard Nixon and the Republican Party. That exodus continued as Democrats made room in their coalition for the era’s counterculture and progressive social movements dedicated to civil rights, feminism, environmentalism, and ending the Vietnam War. Some of these voters did return to the party when the “Boy Governor” from Arkansas, Bill Clinton, led the Democratic ticket, but that resurgence was short-lived.

In the last decade, the Democratic Party’s struggle with working-class voters has become more acute than ever.

More here.

The Deep: Exploring Earth’s Last Frontier

Thursday Poem

Ode to Jacob Blinder

His face stared out into the living room

of my grandparents’ walk-up on E. 13th.

After they died my father hung him

on our staircase wall. Bearded and dour,

great grandfather is now mine, he watches me make coffee,

scour pans, dance my sweetheart

across the floor.

Of Jacob Blinder, I know two things:

he never made it out of Russia,

and of his three daughters,

only the oldest escaped. A constellation of sorrow

followed her as she lay under hay

in a boxcar across Poland, trailed her

on the boat to Buenos Aires.

Tell me, Miriam, how did you stow his portrait—

rolled in your coat hem, a lining in

your satchel, the lost world bound

to your skirt waist?

I am named with his ‘J’—

though he was surely a Yakov—

but when the ocean swallowed

a bitter mouthful, it spit back the old language

at the retreating shore.

When only one thing remains, it isn’t hard

to know what to carry.

by Janlori Goldman

from Split This Rock