Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Thirteen days before the start of the Second World War, a 35-year-old unmarried immigrant woman gave birth slightly prematurely to identical twins at the Memorial Hospital in Piqua, Ohio and immediately put them up for adoption. The boys spent their first month together in a children’s home before Ernest and Sarah Springer adopted one – and would have adopted both had they not been told, incorrectly, that the other twin had died. Two weeks later, Jess and Lucille Lewis adopted the other baby and, when they signed the papers at the local courthouse, calling their boy James, the clerk remarked: ‘That’s what [the Springers] named their son.’ Until then they hadn’t known he was a twin.

The boys grew up 40 miles apart in middle-class Ohioan families. Although James Lewis was six when he learnt he’d been adopted, it was only in his late 30s that he began searching for his birth family at the Ohio courthouse. In 1979, the adoption agency wrote to James Springer, who was astonished by the news, because as a teenager he’d been told his twin had died at birth. He phoned Lewis and four days later they met – a nervous handshake and then beaming smiles. Reports on their case prompted a Minneapolis-based psychologist, Thomas Bouchard, to contact them, and a series of interviews and tests began. The Jim Twins, as they were known, became Bouchard’s star turn.

Both Jims, it transpired, had worked as deputy sheriffs, and had done stints at McDonald’s and at petrol stations; they’d both taken holidays at Pass-a-Grille beach in Florida, driving there in their light-blue Chevrolets. Each had dogs called Toy and brothers called Larry, and they’d married and divorced women called Linda, then married Bettys. They’d called their first sons James Alan/Allan. Both were good at maths and bad at spelling, loved carpentry, chewed their nails, chain-smoked Salem and drank Miller Lite beer. Both had haemorrhoids, started experiencing migraines at 18, gained 10 lb in their early 30s, and had similar heart problems and sleep patterns.

More here.

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review:

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review: 1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’

1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’ The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master?

The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master? I

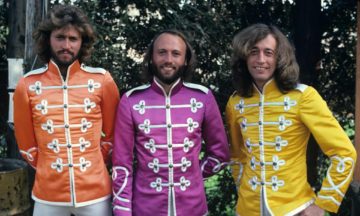

I This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the

This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the  Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity.

Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity. A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book

A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book  According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court.

According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court. T

T For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye.

For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye. On 9 October 1911, Franz Kafka, then 28 years old, wrote in his diary that he didn’t expect to reach the age of 40. At the time of this entry, he was not yet stricken with the tuberculosis that would lead to his death in 1924, shortly before his

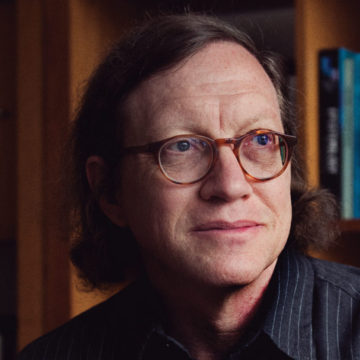

On 9 October 1911, Franz Kafka, then 28 years old, wrote in his diary that he didn’t expect to reach the age of 40. At the time of this entry, he was not yet stricken with the tuberculosis that would lead to his death in 1924, shortly before his  Last year’s Nobel Prize for experimental tests of Bell’s Theorem was the first Nobel in the foundations of quantum mechanics since Max Born in 1954. Quantum foundations is enjoying a bit of a resurgence, inspired in part by improving quantum technology but also by a realization that understanding quantum mechanics might help with other problems in physics (and be important in its own right). Tim Maudlin is a leading philosopher of physics and also a skeptic of the Everett interpretation. We discuss the logic behind hidden-variable approaches such as Bohmian mechanics, and also the broader question of the importance of the foundations of physics.

Last year’s Nobel Prize for experimental tests of Bell’s Theorem was the first Nobel in the foundations of quantum mechanics since Max Born in 1954. Quantum foundations is enjoying a bit of a resurgence, inspired in part by improving quantum technology but also by a realization that understanding quantum mechanics might help with other problems in physics (and be important in its own right). Tim Maudlin is a leading philosopher of physics and also a skeptic of the Everett interpretation. We discuss the logic behind hidden-variable approaches such as Bohmian mechanics, and also the broader question of the importance of the foundations of physics. It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all.

It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all.