Category: Recommended Reading

Lessons from a nuclear life

Jackson Lears in Harper’s:

The war in Ukraine has resurrected the ultimate technocratic fantasy: a winnable nuclear war. Intellectuals at the Hoover Institution are urging American strategists to “think nuclearly again,” reestablishing the idea that nuclear weapons are tools to assert U.S. primacy over Russia and China. This isn’t just talk. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently noted “steadily increasing U.S. bomber operations in Europe”—some near the Russian border. Though most Americans are unaware of it, escalation toward nuclear conflict is already under way.

The war in Ukraine has resurrected the ultimate technocratic fantasy: a winnable nuclear war. Intellectuals at the Hoover Institution are urging American strategists to “think nuclearly again,” reestablishing the idea that nuclear weapons are tools to assert U.S. primacy over Russia and China. This isn’t just talk. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently noted “steadily increasing U.S. bomber operations in Europe”—some near the Russian border. Though most Americans are unaware of it, escalation toward nuclear conflict is already under way.

In this strange atmosphere, I feel moved to revisit my own experience as a naval officer on a nuclear-armed ship more than fifty years ago. My story is all too relevant today. As Daniel Ellsberg demonstrates in The Doomsday Machine, the shape of U.S. nuclear strategy has remained unchanged since the early Sixties.

More here.

Decades-long bet on consciousness ends — and it’s philosopher 1, neuroscientist 0

Mariana Lenharo in Nature:

A 25-year science wager has come to an end. In 1998, neuroscientist Christof Koch bet philosopher David Chalmers that the mechanism by which the brain’s neurons produce consciousness would be discovered by 2023. Both scientists agreed publicly on 23 June, at the annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York City, that it is still an ongoing quest — and declared Chalmers the winner. What ultimately helped to settle the bet was a key study testing two leading hypotheses about the neural basis of consciousness, whose findings were unveiled at the conference. “It was always a relatively good bet for me and a bold bet for Christof,” says Chalmers, who is now co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness at New York University. But he also says this isn’t the end of the story, and that an answer will come eventually: “There’s been a lot of progress in the field.”

A 25-year science wager has come to an end. In 1998, neuroscientist Christof Koch bet philosopher David Chalmers that the mechanism by which the brain’s neurons produce consciousness would be discovered by 2023. Both scientists agreed publicly on 23 June, at the annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York City, that it is still an ongoing quest — and declared Chalmers the winner. What ultimately helped to settle the bet was a key study testing two leading hypotheses about the neural basis of consciousness, whose findings were unveiled at the conference. “It was always a relatively good bet for me and a bold bet for Christof,” says Chalmers, who is now co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness at New York University. But he also says this isn’t the end of the story, and that an answer will come eventually: “There’s been a lot of progress in the field.”

The great wager

Consciousness is everything a person experiences — what they taste, hear, feel and more. It is what gives meaning and value to our lives, Chalmers says. Despite a vast effort — and a 25-year bet — researchers still don’t understand how our brains produce it, however. “It started off as a very big philosophical mystery,” Chalmers adds. “But over the years, it’s gradually been transmuting into, if not a ‘scientific’ mystery, at least one that we can get a partial grip on scientifically.” Koch, a meritorious investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, Washington, began his search for the neural footprints of consciousness in the 1980s. Since then, he has been invested in identifying “the bits and pieces of the brain that are really essential — really necessary to ultimately generate a feeling of seeing or hearing or wanting,” as he puts it.

More here.

Beyond Ozempic: brand-new obesity drugs will be cheaper and more effective

Saima Sidik in Nature:

Two new drugs for treating obesity are on course to become available in the next few years — and they offer advantages beyond those of the highly effective blockbuster drugs already on the market. The first, called orforglipron, is easier to use and to produce, and it will probably be cheaper than existing treatments. The second, retatrutide, has an unprecedented level of efficacy, and could raise the bar for pharmacological obesity treatment. “They’re both breakthroughs,” says endocrinologist Daniel Drucker at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the recent research on either drug. Results from phase II clinical trials of both drugs were announced at a meeting of the American Diabetes Association this month and in the New England Journal of Medicine1,2. Phase II trials provide data on a drug’s efficacy and ideal dosage in a small group of participants.

Two new drugs for treating obesity are on course to become available in the next few years — and they offer advantages beyond those of the highly effective blockbuster drugs already on the market. The first, called orforglipron, is easier to use and to produce, and it will probably be cheaper than existing treatments. The second, retatrutide, has an unprecedented level of efficacy, and could raise the bar for pharmacological obesity treatment. “They’re both breakthroughs,” says endocrinologist Daniel Drucker at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the recent research on either drug. Results from phase II clinical trials of both drugs were announced at a meeting of the American Diabetes Association this month and in the New England Journal of Medicine1,2. Phase II trials provide data on a drug’s efficacy and ideal dosage in a small group of participants.

Acting on appetite

Orforglipron and retatrutide both mimic hormones produced by the lining of the gut in response to certain nutrients. These hormones help to slow the passage of food through the digestive tract and lower appetite by acting on receptors in the brain — both effects that reduce people’s desire to eat and help them to lose weight.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Homesickness as Particle Theory

An atom cannot exist

if the center does not hold.

Matter cannot hold

if the atoms swing apart

too far—

that summer night:

I could feel the pieces of my life

circling away from me in distances so vast

the volume of separation

seemed infinite.

I caught

the wisp of my grandfather’s

pipe smoke,

the saturated indigo

of a green downstate summer evening,

every window open

to the chance of sleep

in deep humidity,

washed in waves of cricket song

and the far pungent howl of a coyote

edging the cornfields.

All in seconds

lifted away.

Sunday, June 25, 2023

Octavia Butler’s Blasphemous Solidarities

Junot Díaz in the Boston Review:

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

For those who do not know her (and apparently there are still plenty who don’t): Octavia Estelle Butler is one of our greatest writers, though in the larger culture she is described as the first Black woman to write science fiction professionally. That biographeme—Black Woman Science Fiction Writer—defined Butler her entire career in spite of the fact that her extraordinary and most well-known novel, Kindred (1979), was not science fiction at all, but a neo-slave narrative that Butler herself described as “grim fantasy.” Butler died in 2006, at the age of fifty-eight, far, far too young, publishing fourteen books (fifteen if we count the posthumous collection, Unexpected Stories). They radically transformed multiple canons—U.S. literature, African diasporic literature, feminist literature, science fiction, speculative fiction—but also radically altered the imaginaries of generations of readers and artists. Now with Kindred on television, in an eight-part series by FX on Hulu, a different set of audiences will have the opportunity to discover Butler for themselves.

More here.

2023 Audubon photography awards winners

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Andrew Pontzen on Simulations and the Universe

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?).

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?).

More here.

Ecological tipping points could occur much sooner than expected, study finds

Jonathan Watts in The Guardian:

Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another.

Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another.

Based on these findings, the authors warn that more than a fifth of ecosystems worldwide, including the Amazon rainforest, are at risk of a catastrophic breakdown within a human lifetime.

“It could happen very soon,” said Prof Simon Willcock of Rothamsted Research, who co-led the study. “We could realistically be the last generation to see the Amazon.”

The research, which was published on Thursday in Nature Sustainability, is likely to generate a heated debate.

More here.

Sheldon Harnick (1924 – 2023) Lyricist

Lisl Steiner (1927 – 2023) Photographer

Teresa Taylor (1962 – 2023) Butthole Surfer

Rural people are so angry they want to blow up the system

Lisa Allardice in The Guardian:

‘Guilty!” American novelist Barbara Kingsolver says when I ask how she feels to become the first writer to win the Women’s prize for fiction twice. “Guilty and delighted,” she says over coffee in a London hotel, the morning after winning the prize for her tenth novel Demon Copperhead. “I don’t want to be greedy. I don’t want to take something that would be more helpful to someone else. It’s my upbringing, I was raised in a culture of modesty.”

‘Guilty!” American novelist Barbara Kingsolver says when I ask how she feels to become the first writer to win the Women’s prize for fiction twice. “Guilty and delighted,” she says over coffee in a London hotel, the morning after winning the prize for her tenth novel Demon Copperhead. “I don’t want to be greedy. I don’t want to take something that would be more helpful to someone else. It’s my upbringing, I was raised in a culture of modesty.”

With a Susan-Sontag silver streak in her hair and steely good humour, 68-year-old Kingsolver is a quiet titan of American literature. Best-known for her mega-selling 1998 novel The Poisonwood Bible and The Lacuna, which won the Women’s (then Orange) prize in 2010, she has taken on uncomfortable subjects such as American colonialism and climate change. She counts Hillary Clinton as a friend and was invited to lunch at the White House with Barack Obama – “One of the most magnetically attractive human beings” – who quizzed her for writing tips. And yet, she rarely leaves the farm in the mountains of south-west Virginia, where she lives with her husband. When she is not writing, she turns her hand to delivering breach lambs. “I’ve done things that risk my wedding band, I’ll just put it like that,” she says, laughing. “When I’m at home, I don’t talk like this,” she says of her east coast accent. “Do you want to hear how I talk? ‘How y’all doing? Ahm’a so sorry-ee,’” she sings with a Dolly Parton twang. Not bad for someone who says “they don’t make people more introverted than me”.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Below the Hill of the Three Churches

The little oyster dragger swings out

on its hawser as far right

as the first flat run of tide in the channel

allows. It panics a frieze of willets into

running left away from its hull, or else

the hull is still and the shifting birds

suggest motion to it, as a ship departing

will seem to set the pier underway; but now

the dragger’s tending left where a

smoke-light skein of least sandpipers

just landed, a shoal creeping forward as

the willets step right, stiff-legged,

mimicking the bridge crossing mud on stilts

far down where a gull begins to slide

on a crawl of heat among exposed hummocks.

Taken with its own effortless riding, it

spins this way on the silt-lift, now that.

Come quick out the door of the Feed and

Grain and ground me with a sack of

sunflower seeds: under three spires

I’d believed rigid until now,

everything’s deviating from the mean.

by Brendan Galvin

from Sky and Island Light

Louisiana State University Press, 1996

Can Plants Think?

Temple Grandin in The New York Times:

In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people.

In “Planta Sapiens,” Paco Calvo, a philosopher of plant behavior, and his co-author, Natalie Lawrence, present the idea that flora are intelligent — that is, capable of cognition. In Calvo’s opinion, people pay more attention to animals than plants and this may explain why some of plants’ remarkable abilities have been overlooked. Our evolutionary history may also shape our reduced attention to the subject; plants are, after all, unlikely to attack people.

Research shows that we are more likely to focus on rapidly presented pictures of animals than those of plants. Studies also demonstrate that while children quickly learn that both humans and animals are living beings, it takes them longer to understand the same thing about plants — indeed, many children do not comprehend it until they are around 10 years old. Calvo refers to this human tendency by a term coined in the 1990s: “plant blindness.”

More here.

Saturday, June 24, 2023

Feasibility Pact?

Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World:

Patrick Bigger and Federico Sibaja in Phenomenal World:

A brewing sovereign debt crisis threatens to engulf as many as sixty-one countries in debt distress over the coming year. Aid flowing from the global North—which carries the most responsibility for the atmospheric carbon stock—to the global South—which bears the brunt of its impacts—must be dramatically scaled up. Despite professing the need for global climate solutions, governments in the more prosperous countries have responded to this threat with lassitude and indifference, as evidenced by the slate of unambitious, unserious, and demonstrably ineffective responses issued from their recent summits. Meanwhile, democratic deficits within the institutions of multilateral governance show the difficulty of grappling with the pronounced asymmetries in our international financial architecture. Even the most ambitious reforms slated for discussion at week’s Summit on a New Global Financing Pact in Paris fail to confront the fundamental role of debt in that asymmetrical architecture.

There is a growing consensus among global South governments, civil society organizations, and even some staff within the twin pillars of the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs), the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, that a thoroughgoing overhaul is required to contend with twenty-first century problems. New governance of the institutions, new trade conditions, and a new debt architecture should all be part of reforms that acknowledge that the main barrier is not access to finance, but who sets the terms and defines the processes of the current economic framework.

More here.

Don’t Believe Modi’s Economic Success Story

Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy:

Tim Sahay in Foreign Policy:

While campaigning for the U.S. presidency, Joe Biden sharply criticized the Modi government’s human rights record, writing how two of its landmark laws are “inconsistent with the country’s long tradition of secularism and with sustaining a multi-ethnic and multi-religious democracy.” Today, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi leads a country that is suddenly at the center of U.S. strategy in Asia. And Biden has changed his tune, inviting the prime minister to a state visit this week.

It’s widely understood that when U.S. elites refer to India having a functional free press, judiciary, and democracy, they are either dishonest or in denial about how the country’s political system has developed under Modi. But the same is true when they praise India’s economy. The U.S. government seems to be operating under the assumption that Modi’s India can sustain the country as it decouples from Chinese manufacturing. There is little reason to believe that is true.

Modi’s “Gujarat model” shot him to the prime ministry in 2014. As chief minister in Gujarat, he had led a developmentalist state: midwifing new industries, repairing bureaucracies, and making huge electricity and infrastructure investments. The state’s growth rate boomed as subsidies were given to politically connected conglomerates and to state-owned players.

But the model has failed when extended to the national stage. While Modi has succeeded in selling himself to his constituents and the world as India’s great modernizer, builder, and attractor of capital, the country’s growth under Modi has flagged.

More here.

All possible worlds

Timothy Andersen in Aeon:

Timothy Andersen in Aeon:

hen I was in my mid-30s, I was faced with a difficult decision. It had repercussions for years, and at times the choice I made filled me with regret. I had two job offers. One was to work at a very large physics experiment on the West Coast of the United States called the National Ignition Facility (NIF). Last year, they achieved a nuclear fusion breakthrough. The other offer was to take a job at a university research institute. I agonised over the choice for weeks. There were pros and cons in both directions. I reached out to a mentor from graduate school, a physicist I respected, and asked him to help me choose. He told me to take the university job, and so I did.

In the years to come, whenever my work seemed dull and uninspiring, or the vagaries of funding forced me down an unwelcome path, or – worse – the NIF was in the news, my mind would turn back to that moment and ask: ‘What if?’ Imagine if I were at that other job in that other state thousands of miles away. Imagine a different life that I would never live.

Then again, perhaps I had dodged a bullet, who knows?

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche said: ‘Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering.’ A life apparently perfect but devoid of meaning, no matter how comfortable, is a kind of hell.

More here,

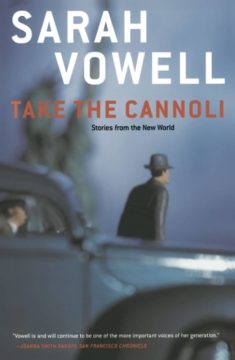

Take The Cannoli, Etc.

Lawrence Weschler at Wondercabinet:

Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive.

Vowell’s unforgettable early contribution to a relatively early incarnation of This American Life (back in 1999), in which she performed a similar feat, though that time unfurling the entire history of the United States drawing on the 720 degree panorama (360 degrees of space compounded by 360 degrees of time) available from just one street corner in Chicago. To wit, this one here: Michigan Avenue as it courses over the Chicago River and intersects with Wacker Drive.

If you’ve already heard that piece, as many of you will have, you should need no reminding: you won’t likely have forgotten it. If not, though, do yourselves a favor and pause right here right now to listen to it right here. (I’m not kidding, just twenty minutes and it may well change how you think about everything from now on—and besides, it’s just so much fun.)

more here.